Making a mark: the shared heritage of the World Game and Australia’s game

As we count down to the AFL (and NRL) Grand Final, and the start of a new A-League season, Paul Marcuccitti ponders why football codes leave fans so divided. After all, as he explains in part one of a two-part essay, they were all spawned from a shared history.

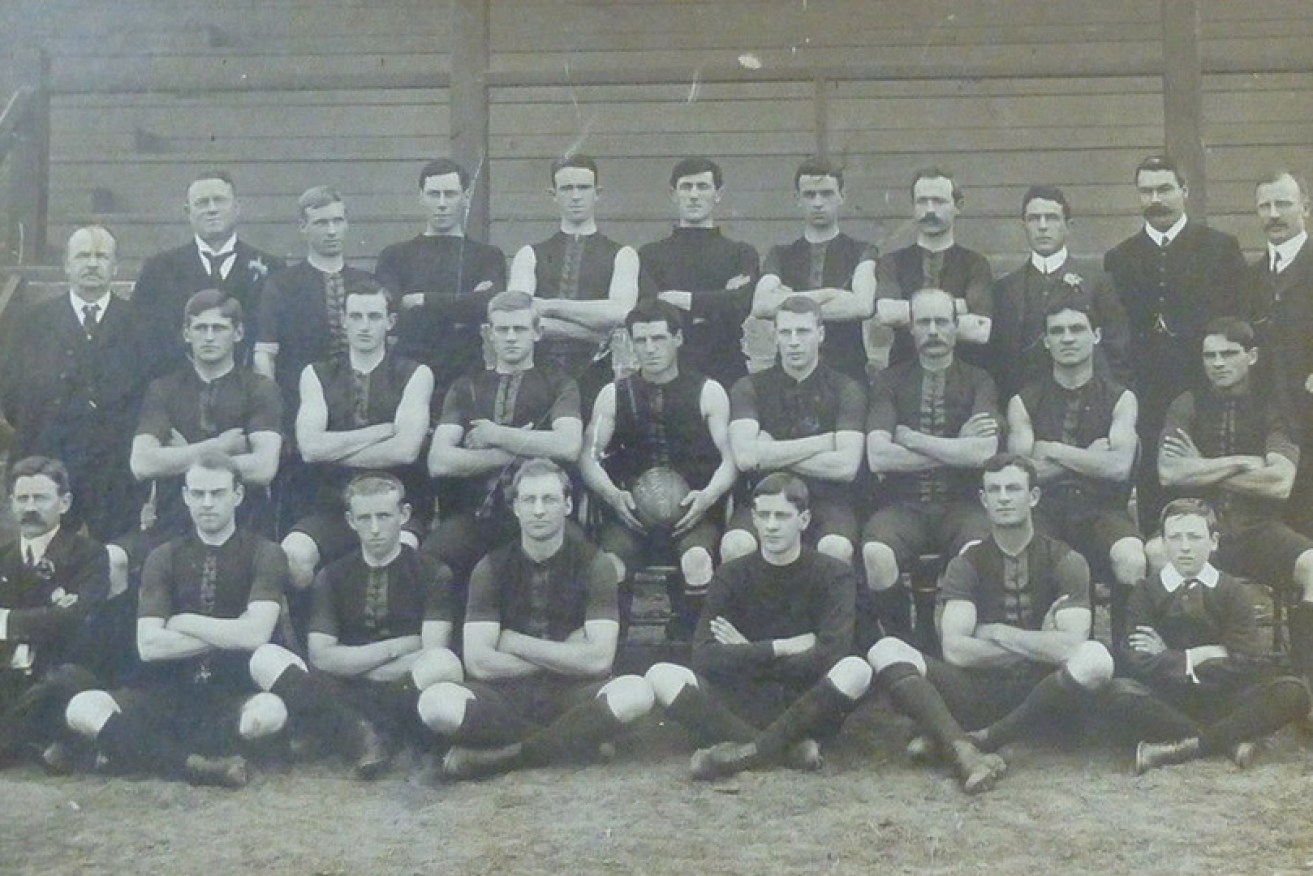

The Norwood Football Club's 1907 team, SA premiers and champions of the Commonwealth. Among its notable players is future BHP mining magnate Essington Lewis (second row, third from left).

Soccer’s critics often point to nil all draws as one of the game’s shortcomings.

And if you’re a fan of a higher-scoring sport, it’s perhaps understandable that you might find it frustrating.

Of course I don’t agree – indeed, though it is a discussion for another day, I maintain that soccer’s low-scoring nature is one of the secrets of its global success.

It has always been thus. Only one goal was scored in the first FA Cup final, played in 1872. That same year, the final score in the first official international (between England and Scotland) was 0-0.

Some of the details in a match report of a game played in South Australia in 1878, which also finished goalless, sound familiar.

Among other things, the write up notes that one of the teams, “…had several chances of scoring, but ignominiously failed in every instance.” Despite that, the report claims that the other team “played a far better all-round game”.

The system of scoring one point for a behind and six for a goal gave the match to the Norwoods, while under the old custom the Ports would have won

Leaving aside that today’s sport writers haven’t been known to use “ignominiously” too often, those words could easily describe some modern day soccer matches.

But, in fact, the match was part of the 1878 South Australian Football Association season – and that Association would eventually become the South Australian National Football League.

It was played at Kensington Oval between the home team, Kensington, and a nearby club that had been founded earlier that year: Norwood.

The Redlegs would be undefeated in 1878 and they won the premiership. But, to confirm how different the game was then, Norwood played in four nil all draws (including a game against Port Adelaide which was described as “one of the roughest” of the season) and conceded just one goal all year.

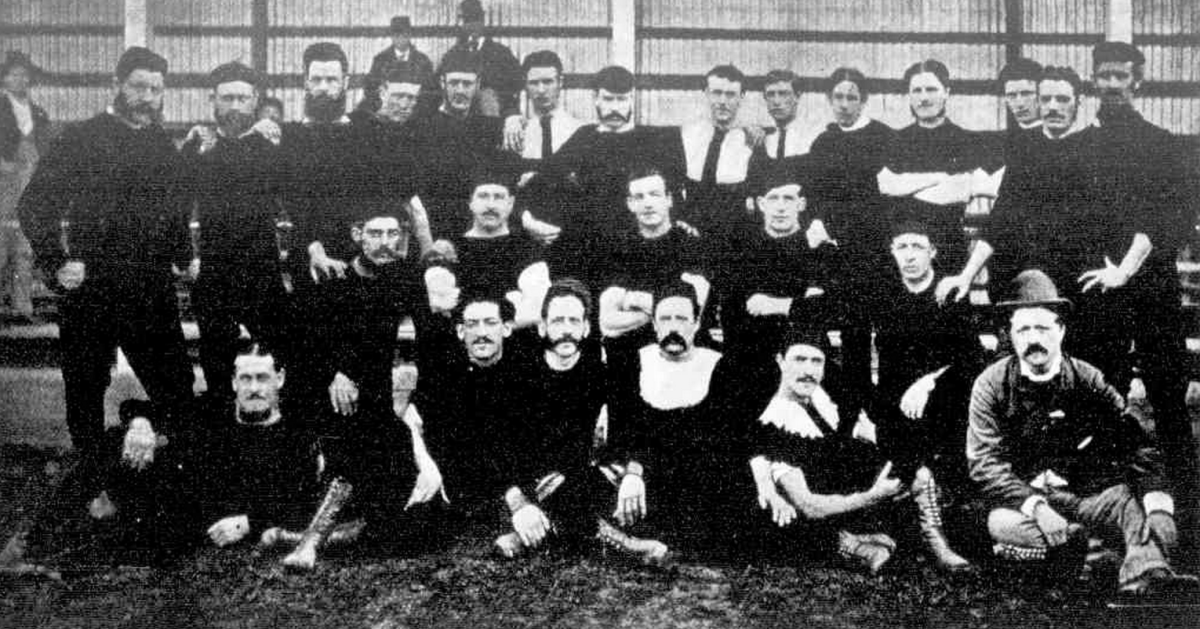

Norwood’s 1878 team. Photo: Norwood Football Club / Wikipedia

Kensington Football Club disappeared a few years later but it had already played a big role in the sport’s South Australian history. It had developed a set of rules which included the goals having crossbars.

But others, notably the Adelaide Football Club of the time, supported different rules. Matters came to a head in 1876 and a little known chap called Charles Cameron Kingston carried the day.

State parochialism demands that this next part is rarely mentioned: the rules that would be adopted (just in time for 1877, the inaugural South Australian Football Association season) were those used in Victoria. There were just a few amendments made to the “Melbourne Football Rules” so that some local ones could be retained.

Scoring would slowly become more frequent over the next two decades but, though they would be tallied, behinds didn’t count. Back at Kensington Oval in 1880, a match between the home team and Port Adelaide resulted in a draw despite the visitors registering 2.12 to Kensington’s 2.4.

The year 1897 is recognised as the Victorian Football League’s first and it began with eight clubs which left the Victorian Football Association. It was also the year that brought in six points for a goal and one for a behind (among other rule changes).

An acceptance of Victoria as the rule makers appears in the South Australian Register in March of that year. Under the heading “New Rules Of The Australasian Game” it describes: “… the principal amendments which have been made by the Victorian League in the rules of the Australasian game of football, and which will probably be adopted by the South Australian Association.”

The new scoring system is explained as follows: “It has been enacted that ‘the side securing the greater number of points shall win the match, and that a goal shall count six points and a behind one.’ To apportion fair values to goals and behinds respectively proved a delicate undertaking, and the ratio of 6 to 1 was adopted only after a long and careful consideration. The trouble was to secure for behinds just so much recognition as would compensate the attacking party without offering an inducement to defenders to help the ball behind.”

Thank goodness no one ever had to worry about defenders deliberately rushing behinds again.

Only two months after that story about the new rules was printed an early season match saw Norwood 3.11 (29) defeat Port Adelaide 4.2 (26).

Under the heading “Red-And-Blues Win By Points”, the Evening Journal noted that: “The system of scoring one point for a behind and six for a goal gave the match to the Norwoods, while under the old custom the Ports would have won. Still, it is the fairer method, and undoubtedly on the general play the Norwoods were a trifle better than the magentas.”

(Yes, the magentas. That’s true Port Adelaide tradition.)

The original laws of “The Australasian Game” were written in 1859 under the heading “Rules of the Melbourne Football Club”. The celebrated Tom Wills is one of the sporting pioneers named on the document.

We know a bit about Wills – an outstanding cricketer who championed football for the winter months. He did this not long after returning to Australia from England where he also played the version of football then in place at Rugby School.

But the other sportsmen who created the first laws – JB Thompson, William Hammersley and Thomas H Smith – are no less worthy of mention. They all moved to Australia as adults (Thompson and Hammersley from England; Smith from Ireland).

It would defy all logic to imagine that the codes of football these chaps would have known in the British Isles didn’t guide their decisions.

And most of the first rules they wrote are too similar to those that were in use in some parts of England to be coincidental, particularly those of Rugby School (first written in 1845), the Cambridge Rules (1848) and possibly the Sheffield Rules (1858).

I will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen, who would beat you with a week’s practice

In 1863 the Football Association (FA) was formed in London and tried to get the clubs and schools that attended to agree on common rules. There was some success but Mr FM Campbell of Blackheath Football Club could not agree with Law 10. It banned tripping and “hacking” (kicking an opponent’s shins).

Campbell famously warned that removing hacking would “do away with all the courage and pluck of the game, and I will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen, who would beat you with a week’s practice.”

The result of this disagreement was that Blackheath and other clubs who played “the rugby-type game” formed the Rugby Football Union in 1871.

(The RFU immediately banned hacking and France subsequently became one of England’s toughest opponents in international rugby. No doubt Mr Campbell would say those two things are related.)

But let’s return to the Melbourne Football Club’s 1859 laws. There were just ten and they resembled rules used in the English codes. Particularly Rule 2: “The captains on each side shall toss for choice of goal; the side losing the toss has to kick-off from the centre point between the goals.”

Rule 3 appears to be unique: “A goal must be kicked fairly between the posts, without touching either of them, or a portion of the person of any player on either side.”

But not quite. Wills would have known the “try at goal” rule from rugby which, among other things, stated that the ball “must go over the bar and between the posts without having touched the dress or person of any player.” (At the time, there were no points for tries in rugby. But what we’d call a try now had to be achieved to earn a punt at goal – which defenders could try to spoil by charging towards the kicker.)

Marking the ball (Rule 6) was known in English codes of the time.

If a player makes a fair catch he shall be entitled to a free kick, provided he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once

The Sheffield rule was: “A fair catch is a catch from any player provided the ball has not touched the ground or has not been thrown from touch and is entitled to a free-kick.” The fair catch was also the very first of Rugby’s 1845 laws.

It would even make it into the 1863 FA rules: “If a player makes a fair catch he shall be entitled to a free kick, provided he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once; and in order to take such kick he may go as far back as he pleases, and no player on the opposite side shall advance beyond his mark until he has kicked.”

Yes, handling the ball was once permitted in association football. It didn’t last long. And, in case you were wondering, there is no rule telling Aussie Rules players to make a mark – those that do so possibly think the umpires need their help.

The original Rule 8 was also popular in England: “The ball may be taken in hand only when caught from the foot, or on the hop. In no case shall it be lifted from the ground.”

Sheffield’s law was: “It is not lawful to take the ball off the ground (except in touch) for any purpose whatever.”

And Cambridge stated: “When a player catches the ball directly from the foot, he may kick it as he can without running with it. In no other case may the ball be touched with the hands, except to stop it.”

Indeed, running with the ball was associated with the rugby game. The story that it was invented because William Webb Ellis “with a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time first took the ball in his arms and ran with it” may not be entirely true, but that it was a departure from normal forms of football certainly is.

Rule 9 was another Cambridge special: “When the ball goes out of bounds (the same being indicated by a row of posts) it shall be brought back to the point where it crossed the boundary line, and thrown in at right angles with that line.”

Actual Cambridge: The ball is out when it has passed the line of the flag-posts on either side of the ground, in which case it shall be thrown in straight.

Finally, Rule 10 stated: “The ball, while in play, may under no circumstances be thrown.” While that didn’t have a written equivalent in Cambridge or Sheffield, other rules showed that when the player legally took possession of the ball it had to be kicked.

The Swans and Bulldogs will do battle in the AFL’s decider on Saturday. Here, Toby Nankervis and Jordan Roughead fight for a mark – a feature of Australia’s game that was once allowed in soccer. Photo: Paul Miller / AAP

Most of the rules I haven’t mentioned mainly deal with distances (e.g. between goals, and how far a ball could be brought in for kick offs after it had gone behind). Also Rule 7 allowed tripping and pushing but not hacking. It might have been a compromise, as Rugby allowed all three while Cambridge allowed none.

The influence of Rugby School’s rules is unsurprising given Wills’ years there. But both JB Thompson and William Hammersley were Cambridge men.

Indeed Thompson was at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1848 – the same year Trinity hosted a meeting with representatives of several different colleges which resulted in its famous laws. Of course those schools had their own rules. They included Eton, Harrow, and Winchester; Thompson knew all their codes.

William Hammersley also attended Trinity. And he must have remained in England until 1856 as there are records of him playing cricket there until then. In January 1857, he played a first-class match for Victoria against New South Wales. Wills was one of his teammates.

But the shared history of our football codes isn’t limited to rules that were commonly used among them.

Paul Marcuccitti is a co-presenter of 5RTI’s Soccer on 531 program which can be heard from 10am on Saturdays. His analysis will continue on InDaily tomorrow.