The extraordinary life and legacy of Bob Quinn

One of South Australia’s greatest footballers proved himself as a courageous leader on the playing fields of Australia and the battlefields of north Africa during World War II. His fame has rightfully grown long since he left both endeavours, and the accolades continue with induction to the SA Sport Hall of Fame.

Bob Quinn is the first inductee to the South Australian Sport Hall of Fame for this year. Read InDaily throughout February to discover the others.

Lest we forget.

One of Port Adelaide’s first cult hero footballers, Harold Oliver, died in Adelaide in 1958 with his funeral noted for the absence of the admirers who flocked to Adelaide Oval before World War I to marvel at his talents as an all-round player with an exhilarating leap.

Half a century later, in September 2008, the man who followed Oliver as a football hero at Alberton, Bob Quinn, died at age 93, with his fame probably greater than during his two decades as a league footballer with Port Adelaide in the SANFL.

A grandstand carries the Quinn name at Port Adelaide’s spiritual home at Alberton Oval. The northern gates at Adelaide Oval honour Quinn. He is a member of the Australian football and South Australian football halls of fame. And each Anzac Day since 2002, the most courageous and team-minded footballer in the SANFL grand final rematch at Adelaide Oval is honoured with the Bob Quinn Medal.

Today, Sport SA has announced that Quinn’s name will be rightfully placed in another pantheon of sporting achievement, the SA Sport Hall of Fame. The occasion sparks this thought: How would one of the most modest and humble achievers in South Australian sport want to be remembered today when the spirit of the Anzac tradition is so strong and the game of Australian football is so powerful? As a sporting hero or a war hero?

The “MM” by Quinn’s name on the northern stand at Alberton Oval is not in recognition of his two Magarey Medals, earned on each side of his war-interrupted career – the first in 1938 when Quinn was arguably the best rover in South Australian football; the second in 1945 after he had returned from war service with, as his family and team-mates recall, half a leg “blown off” by enemy fire to his right thigh. The “MM” script on the grandstand forever recalls Quinn’s Military Medal for taking command of the 10th platoon at Tobruk to dismantle a barbed-wire barrier before attacking an enemy post while facing the threat of death from the spray of machine guns.

Today, 70 years after Quinn last coached the South Australian State team, the boy who ran from Exeter and rowed across the Port River to train at Alberton Oval is appropriately remembered as a hero, not just as a sportsman but as a soldier on true battlefields.

Which would give Quinn greater pride?

“It’s a good question … and the first time anyone has asked,” says Greg Quinn, one of Bob’s two sons and four children. “And it is a difficult question for me to answer, but I will now think of it for some time. It is a very good question.”

He was worried about losing his leg. I was worried about him losing his life.

There is no doubt Quinn found great enjoyment in his football, particularly at Port Adelaide where he was continuing a family tradition that dates to the club’s inception in 1870. He had won three SANFL premierships (1936, 1937 and 1939) before enlisting for war service. He had the 1938 Magarey Medal to his name. He was twice club champion at Port Adelaide with the 1937 and 1938 best-and-fairest titles. He had represented South Australia with honour and such class that VFL clubs St Kilda, Richmond and Geelong (where his brother Tom was building his star status) were keen to sign Quinn – and were seeking rule changes on procuring non-Victorian players for their clubs.

“He had no reason to play again when he came home (from the war),” says Greg Quinn. “But he did … because he loved his football club. That’s what Dad did, he played football. He came from a family of 10 kids. He scratched and scrounged for everything he could get at home. And he was pretty good at kicking and catching a football.

“But he also loved his comrades. Every first Friday of every month, Dad (as publican of the Southwark Hotel on Port Road) would knock off at midday to be with 25-30 of his mates from the Second 43rd (battalion) for their reunion.

“Dad loved his football. He loved his mates from service.

“It is the first time anyone has asked me where he would find his greatest pride. I know he loved the people he met from both football and in service. That was Dad: he loved people. That is what made him a great publican too (in the city and at Kadina).”

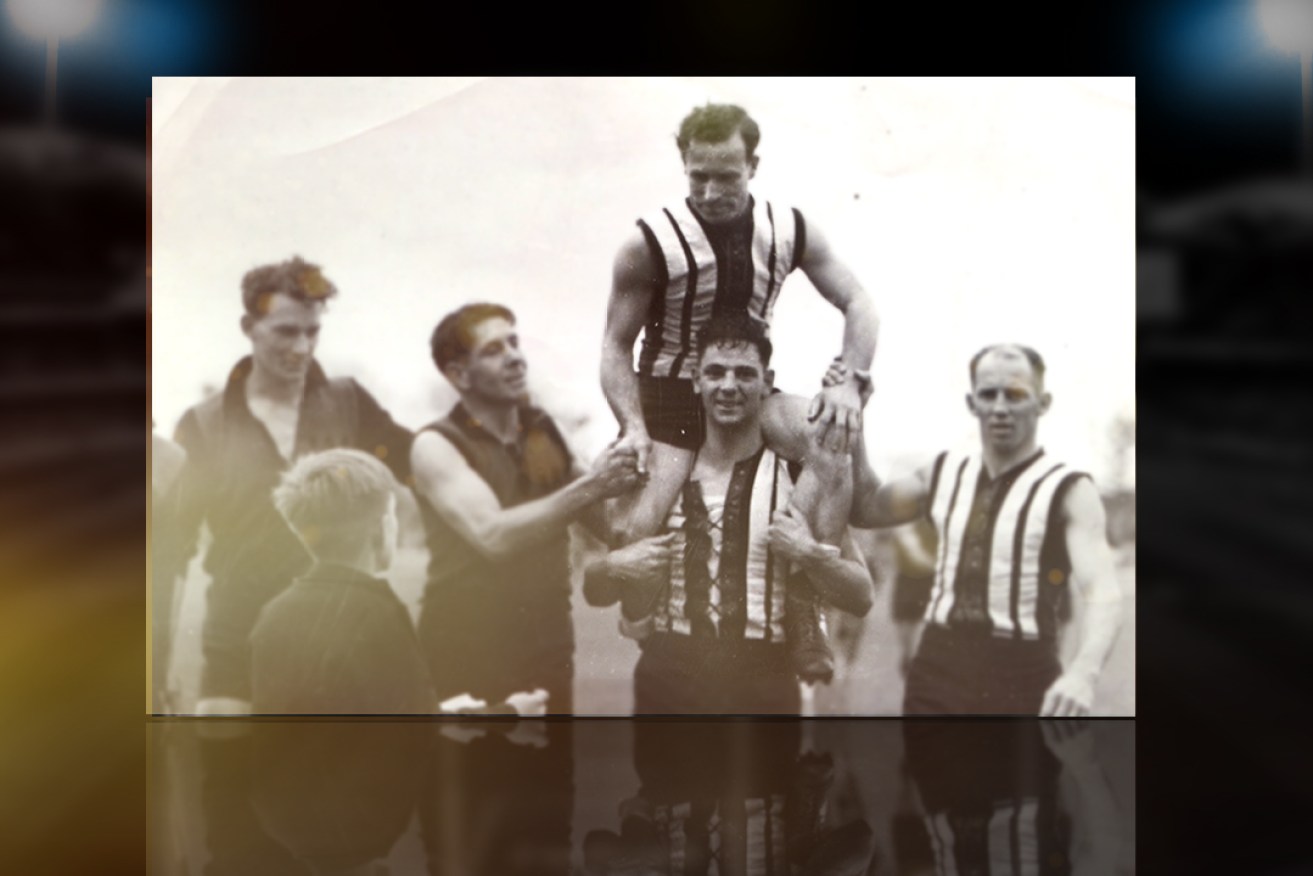

Bob Quinn, after the war, wearing the Port Adelaide jumper of the time. Image supplied by Port Adelaide Football Club

Quinn left Port Adelaide after enlisting with the AIF in June 1940. He had already established his greatness in South Australian football. After his return in 1944, carrying serious injuries to an arm, his right leg and his face, Quinn made his name stand among the immortals in Australian football.

Quinn was the first captain of an All-Australian team in 1947. He was honoured with his second Magarey Medal in 1945. He achieved another two best-and-fairest titles at Port Adelaide in 1945 and 1947. He topped Port Adelaide’s goalkicking list in 1945.

And of all the stories that could be told of his 266-game league career in club and state football, there is always the tale of the day at Princes Park in 1946 when Quinn carried South Australia as captain-coach from a 39-point deficit at half-time to a draw against the Big V of Victoria – the year after Quinn had defied the Victorians as best-afield in South Australia’s stunning 52-point win at Adelaide Oval.

That state game in 1946 began with a doctor knocking on the changeroom doors of the South Australian team after he had seen the “Quinn” name in a morning newspaper and recalled how five years earlier in north Africa he operated on a soldier named “Quinn” who had made such an issue of keeping his right leg … because he had to play football on returning home.

The doctor made his way into the changerooms, told Quinn to hop onto a table so he could see his right leg and after a quick examination declared: “Bloody good job I made of that, didn’t I?”

On leaving the rooms, the doctor told one of the state team officials: “He was worried about losing his leg. I was worried about him losing his life.”

Quinn’s reputation was made by his courage, his devotion to hard work and his commitment to the football club he loved and the game he treasured. He thrived in an era when there were no halls of fame nor the accolades that put names on grandstands, turnstiles or the pedestals of statues.

So how would Quinn cope with today’s adulation and the obligatory acceptance speech?

“Not particularly well,” says Greg Quinn. “Dad was a very good public speaker.”

This was most noted in 1946 when every football journalist on each side of the SA-Victorian border went to great lengths to learn just what Quinn had said at half-time to his battered South Australian team to gain such a grand response against the Big V at Carlton. That South Australian State team led by 24 points with 10 minutes to play and the Victorians salvaged a draw by putting a heavy focus on Quinn.

“Dad always said, ‘If you have to read a speech, it is no bloody good. It has to come off the cuff and from the heart. Not from a piece of paper’.

“Dad was a very good wordsmith. He spoke very well at football presentations. But if it was going to be about him, he would prefer to say nothing. He was not for any backslapping.

“He would be proud, but he would not be keen to make an acceptance speech. He would enjoy all these accolades today. But speaking of himself was not Dad.”

Indeed, it is a picture that says a thousand words about Bob Quinn’s status in South Australian football and sport (full image below). It is from his last match as a Port Adelaide player in the 1947 SANFL preliminary final against West Adelaide, a match his beloved Magpies lost. Quinn is carried off Adelaide Oval with the notable adulation of his West Adelaide rivals who wanted to honour a rival before they celebrated securing a grand final berth.

Fellow Magarey Medallist Jeff Pash later wrote that Quinn had played the game of Australian football with “confident dignity”.

“He had a great turn of speed with the ball, but he seemed to be leading a procession rather than flying from pursuit,” Pash added. “As a footballer, he was impeccable in all his movements and the range of accuracy of his drop-kicking was the most remarkable in my experience.

“I shall never forget the spectacle of him playing on in a match while holding a broken arm to his side.”

This was the Bob Quinn who kept charging enemy lines at Tobruk with a badly wounded right leg. Lest We Forget.

The latest inductees to the 2023 South Australian Sport Hall of Fame will be celebrated at a gala event at Adelaide Oval on March 3. Go here for tickets and more information.

InDaily is the media partner of the South Australian Sport Hall of Fame.