Who is – and who is not – to blame for the housing crisis

Accusing councils of holding up development is a lazy take on our national housing shortage, argues Michael Pascoe.

Photo: TND/Getty

As certain as “the Coalition” being the answer if you ask Siri for an example of a policy vacuum, Labor and Greens are kicking off the political year fighting over housing policy that doesn’t add up to much.

As predictable as a Murdoch culture war, the fight is running over old ground, offering nothing meaningful, being about headlines rather than substance.

And as reliable as five-second television news grabs being vacuous, reporting of it repeats misinformation and nonsense shibboleths.

For example, a Channel 7 report on the Labor v Greens barney includes an economist saying: “What you need to do is to get councils approving more.”

My guess is that the economist in question would have said considerably more, but five seconds is all that’s allowed so the viewer ends up with a misleading cliché.

No, councils are not to blame for the housing crisis. They are not responsible for the shortage of housing.

Sure, “everybody” says councils are holding up building more housing.

Back in the day, “everybody” used to say the way to treat a brown snake bite was to cut between the two puncture holes and suck out the poison. (Remember to spit.)

“Everybody” was wrong then about venomous Australian snakes and is wrong now about blaming councils.

Sure, some councils could make building easier for developers and individuals, but that’s not what the housing crisis is about.

Before a council can approve an application, the application has to be made. Turns out applications and approvals are pretty much in balance – proportionately very few are rejected and there are generally more approvals than dwellings proceeding.

It also turns out there is a large stock of potential housing already approved, but those planning approvals are being sat on by developers awaiting the most profitable moment to start building.

On top of that, there is something of a credit squeeze happening with banks leery of lending to builders, having watched so many go broke over the past year.

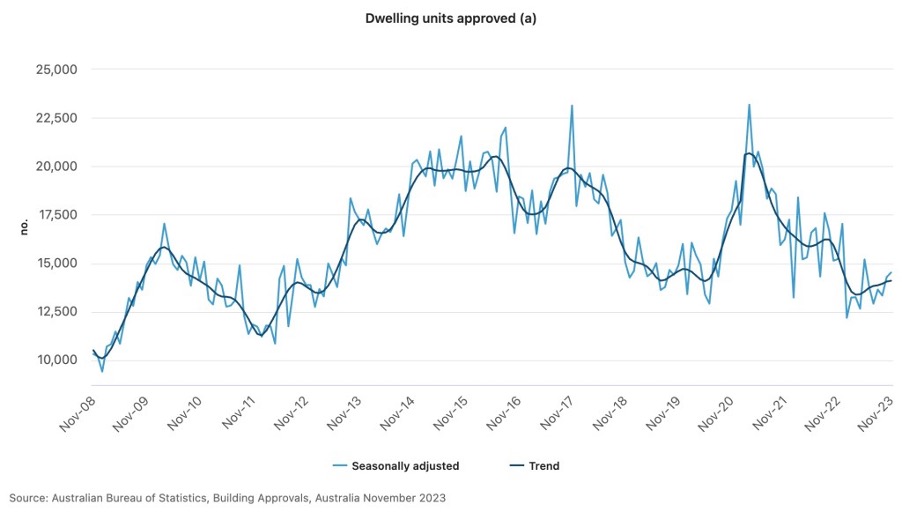

Building approval numbers are easily acquired – the Australian Bureau of Statistics publishes them monthly.

Oh look, fresh figures just out on Tuesday – they bounce around a bit but vision-impaired Frederick can see they are nowhere near the 20,000 a month we need to average to achieve the promised 1.2 million homes over five years, let alone the 1.3 million stretch target.

Figures for applications and completions are not as easily or frequently proffered. For context there, I asked two actual housing experts, UNSW’s Dr Cameron Murray and independent analyst and property buyer, Pete Wargent.

Wargent used Victorian Department of Transport and Planning stats to demonstrate that, indeed, approvals can only be made after they are applied for.

Obviously, there is an element of flowover from previous months, but in the first half of this financial year 19,231 planning permit applications were received, 2569 were withdrawn or lapsed and only 532 were refused.

Not only is the planning/approval process not to blame for the shortage of dwellings, it is running ahead of developers willing and/or able to build.

Murray – previously referenced in this space as one of the few economists bringing fresh analysis to the real estate industry-dominated housing shouting match – has an explainer ready to go on the subject, something he has been scathing about in the past. (What Murray calls “owners”, most of us would call “developers”.

“A planning approval is the first step in a development process and a building approval is the last step prior to construction,” he writes. “A planning approval is needed to assess a project against planning regulations, and a building approval assesses a building against the building codes.

“Because there are risks in property, usually between planning and building approvals property owners will pre-sell. Because of this, the market regulates how quickly planning approvals are converted into dwellings. When the market is booming, many approved projects are pushed through to construction. When the market is soft, approved projects are delayed, increasing the buffer stock of projects with planning approval.

“Market risks, variations, and lags mean that it is sensible for property owners to keep a buffer stock of planning approvals. They can then respond quickly to new market conditions by selling and starting construction, by delaying without major capital commitments, or by varying the approval and seeking a new one for a different project that meets new market preferences.

“But they don’t need to keep a buffer stock of building approvals because these are quick and come after the sales have verified the project is viable.”

Murray uses Queensland for an example of just how big those buffer stocks are: At the current rates of new construction, five or six years’ worth of detached housing lots.

So forget the developers’ whinge about planning approvals limiting supply – it’s a distraction from the main game of needing bigger governments than your local council to push ahead building themselves when the market won’t.

As written here before, the policy failure decades in the making has been federal and state governments steadily withdrawing from providing sufficient public housing.

The federal and state governments are talking about no longer shrinking the proportion of public and social housing, but the various announcements and promises so far don’t add up to actually solving the problem. They are struggling to play catchup.

The latest promised fight has the Greens looking to repeat their success in leveraging extra funds out of the Albanese government for public housing.

Adam Bandt’s push for rent freezes and caps will do nothing to solve the problem of supply.

Blocking Labor’s $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund election slogan enabled the Greens to claim credit for an extra $3 billion for public housing – a definite win, yet still small given the scale of the shortage.

But the political problem with giving into blackmail is that it encourages the blackmailers to try again.

Thus Adam Bandt is back pushing rent freezes and caps, which do nothing at all to solve the problem of bringing on more supply but sound good for the renter voters the Greens are chasing.

Hopefully, Bandt will have more success is winning more direct funding for public housing, pushing governments to directly add supply.

As for the Labor “Help to Buy” co-equity policy they’re fighting over, it promises to help some individuals into home ownership, individuals who might well thank Labor.

But, like first-home-owner grants, it doesn’t help solve the bigger problem, particularly when this iteration includes buying existing housing. It effectively increases the money some people have to compete in the existing market, pushing up prices.

And where’s the Coalition? Nowhere.

The Opposition housing spokesman is Michael Sukkar, who carries the embarrassment of being the Housing Minister from 2019 to 2022.

That’s when the Morrison government ignored the advice of just about every economist to invest in public housing as COVID stimulus, instead unleashing the disastrous HomeBuilder scheme, originally costed at $688 million but ending up being $2.3 billion thrown at individuals who mostly did not need it.

The lack of thought and control in HomeBuilder sparked the serious inflation in building costs that we’re still paying for.

Sukkar, whose main apparent skill is running Victorian Liberal Party branch numbers, has called Help to Buy “underwhelming”, trotting out a line that sounds like it has been extensively workshopped by the entire Coalition brains trust:

“Those who want to buy a home want to own it themselves, they don’t want the government owning a portion and have Anthony Albanese sitting at the kitchen table.”

Oh, such wit, such cut-through – such mindless vacuity.

Sukkar knows plenty about being underwhelming. Next he’ll be blaming councils.

This opinion piece first appeared in our sister publication The New Daily.