Why home ownership can’t be our only goal

The new reality of soaring South Australian house prices must not entrench wealth inequality, argues Susan F. Stone.

The stresses related to the current housing crisis are well documented.

The crisis can be defined across many issues, including ever-increasing mortgage payments, the inability to access housing whether it be through renting or buying, or an inability to have needed repairs done or renovations completed. In some sense, the changes that have occurred in the market in such a short time have been truly remarkable. It’s difficult to believe that this time last year, the cash rate stood at 2.85 per cent and there was speculation of rate cuts in 2023.

However, in another sense, today’s housing crisis is an old story and one that has little to do with interest rate hikes.

A 2008 Parliamentary Inquiry showed that housing starts were still falling short of projected demand by roughly 15,500 units a year for the five years the study examined. The inquiry stated that the shortfall in housing supply could be traced to three particular challenges: the need for developers and councils to establish a high-quality urban environment with supporting infrastructure; clear and efficient state government planning processes; and an adequate and skilled construction workforce.

None of these challenges have been adequately addressed in the intervening years.

According to the South Australian Treasury, the State will need between 95,000 and 115,000 additional dwellings by 2032. In the meantime, according to the 2021 census, there are more than 7400 South Australians homeless, a 19 per cent increase over 2016. Given the current rental crisis, the actual number is almost certainly higher.

Construction is one of the strongest components of the South Australian economy, contributing 0.2ppt to the State’s recent GSP. InDaily’s South Australian Business Index reported that South Australian construction companies are among the strongest performers in FY2023, with average revenue growth of 23 per cent and individual company growth ranging from 8 to 50 per cent. However, much of this growth is based on existing construction projects.

Going forward, we can expect to see these numbers fall with both national and state building approval numbers falling. While total housing approvals in South Australia increased slightly by 0.8 per cent in October, they are still trending down for the year. The trend for housing approvals was down 0.9 per cent in South Australia in October with total building approvals down 3.0 per cent. Only New South Wales showed a larger decline.

This decline in dwelling approvals could be a big problem on many levels as the industry works its way through its current backlog, leading to the number of new housing ventures to fall.

This lack of supply is adding to the difficulty of acquiring a house or unit by putting pressure on prices.

The median price of a house in metropolitan Adelaide in September 2023 was just over $710,000. Before COVID (December 2019) it was $485,000 – a 47 per cent increase. In the prior 4-year period (2016-2019) the median house price increased only 8 per cent. While housing prices across the country have increased, the growth has been especially strong in South Australia

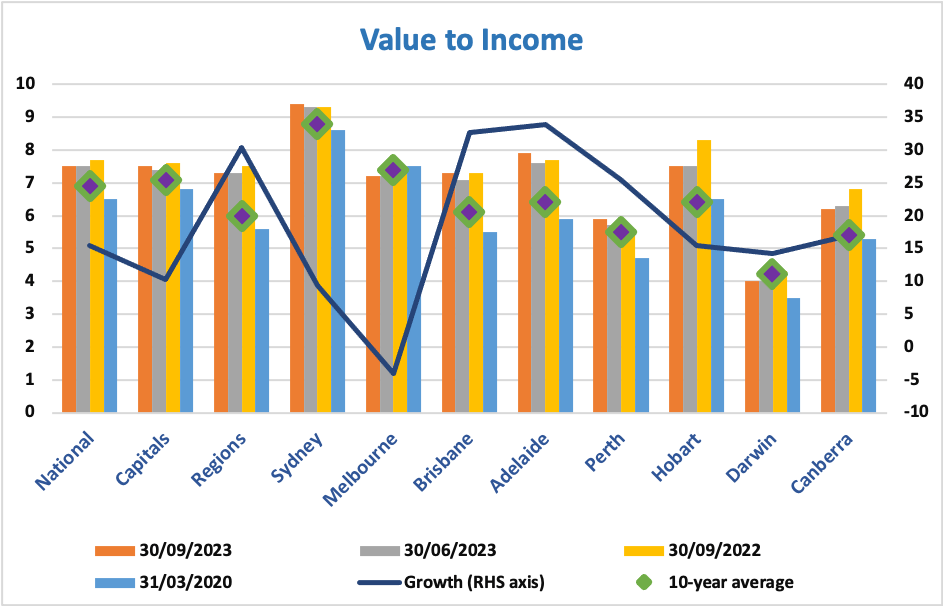

The recent ANZ/Corelogic report on housing affordability makes this all too clear. The median value of a home in Adelaide, as a multiple of the average income, has grown 34 per cent in Adelaide – more than any other capital city.

This substantial increase in the value of a home compared to an average income puts home ownership out of reach for many working South Australians. For those who own a home, this passive increase in wealth helps spur spending and security. For those trying to break into the housing market, it means that their income will buy them less house.

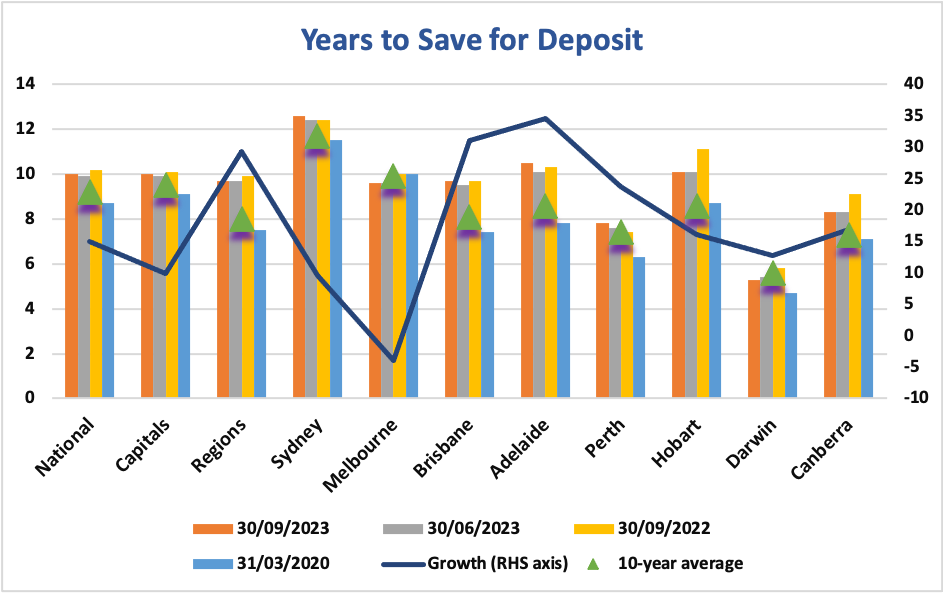

The difficulty in buying a house is illustrated by the time it takes to save for a deposit. Once again, the biggest increase has been in Adelaide.

Just before COVID (March 2020) it took roughly 7.8 years to save for a deposit when buying a house in Adelaide, compared with 9.2 years nationally. Now it takes someone 10.5 years in Adelaide compared with 10 years nationally. The only capital city with a longer period is Sydney. Adelaide’s housing market is quickly becoming one of the most challenging in Australia.

Going forward the government has announced several initiatives to help stem this tide (see for example here). But these will take time to come online.

The inherent inequalities associated with home ownership and access to such ownership mustn’t be allowed to persist.

Economic research has shown that access to assets (wealth) leads to better outcomes for individuals across several measures, including education, health and future earnings. It also shows that wealth inequality can be even more detrimental to social cohesion and mental health than income inequality. Indeed, people can easily know the value of their colleagues or neighbours cars or home, but it is difficult to find out their annual salary.

In addition, to the extent that economic inequality adversely affects the health of less well-off individuals through psychosocial stress and frustration associated with their relative standards of living, wealth inequality may be a more important determinant of health-related outcomes than income inequality.

We need to ensure that home ownership doesn’t come to define our worth or our potential.

Susan F. Stone is the Credit Union SA Chair of Economics at the University of South Australia.