Mental Health is a human right, unless you become unwell

To mark World Mental Health Day, Geoff Harris considers how South Australia is stacking up when it comes to the basic human right of being abile to live in your community with good mental health and access support when needed.

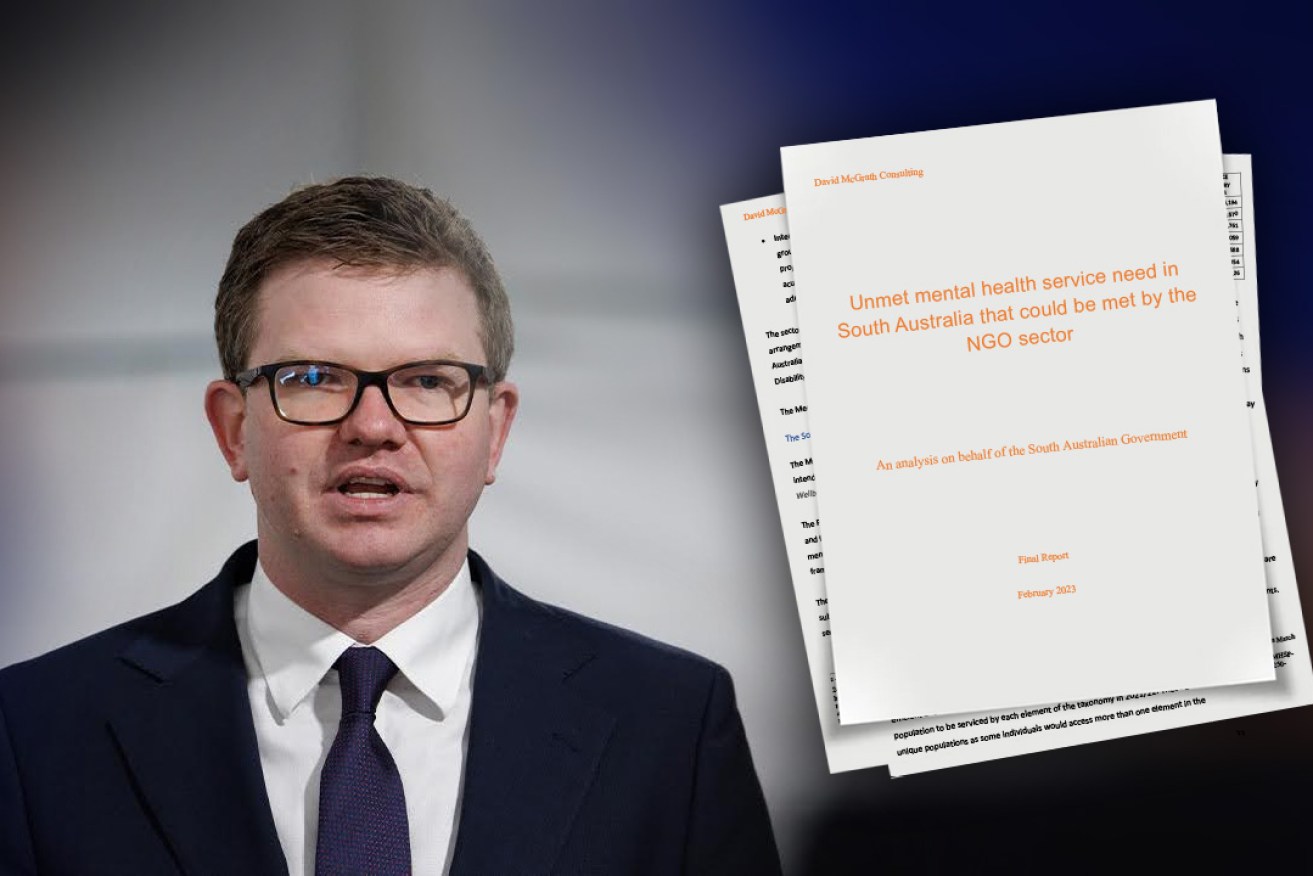

Health Minister Chris Picton released the Unmet Needs Study on July 25, 2023.

A few months ago, the Mental Health Coalition of South Australia pressed the State Government to release a report that SA Health had completed back in February this year. It was a report that said 19,000 South Australians with complex mental health challenges were living without the support they needed to live well in their community. Something the World Health Organisation would say is a breach of their human rights.

That is a lot of South Australians.

These 19,000 are not anonymous. They are people who are cycling in and out of emergency departments and hospital wards, they are living alone or being cared for by ageing families. They are sleeping rough or in insecure housing. They are in our correctional system, dropping out of education or losing their jobs.

They are people who could be living well with their mental health challenges but are becoming unwell and watching their life spiral because no one is there to help them navigate what they are going through.

They are across all ages and demographics and around a third are living in rural and regional areas.

This figure of 19,000 South Australians did not just appear overnight.

The Productivity Commission told us there were 11,000 in 2019, but that number has almost doubled in four years. We got here because of a gradual process of defunding mental health services that prevent people from falling into crisis. It began with the rollout of the NDIS and a shift of funding.

Do you remember talk about the ambulance at the cliff face all those years ago? Well, now we know what it looks like when it falls off.

But not everyone is going without support.

From the 25 per cent of people living with complex mental illness who are getting the day-to-day support we refer to as psychosocial support, the benefits are clear. There is a reduced number of them presenting to emergency departments needing crisis support. They are being supported to find secure housing and the ability to retain it. They are being assisted to work through complex problems like family violence and relationship breakdowns. They are retaining employment, volunteering in their communities and basically living well.

The remaining 75 per cent cannot get access to the support they need to avoid the churn through emergency departments (and then being blamed for the pressure on the system), unemployment, housing stress, homelessness, drug and alcohol issues.

Then there is the pressure on family and friends to fill the gaps in a system that cannot meet their needs, there is pressure on GPs and other services that are trying to meet a growing demand.

By sitting on this report, the South Australian Government lost an opportunity in this year’s state budget to actually fund and support these South Australians, their families, friends, employers, educators and community.

Initially, we thought it meant being left to wait another year for funding. However, the State Government’s response of handing the report to the Commonwealth to fix has meant we are going to wait for years because we are the first state to undertake this research.

The Mental Health Coalition of SA asked for the research prior to the 2022 state election and the then health and wellbeing minister Stephen Wade set it in motion before leaving office.

However, despite being the first state to complete it, we now have to sit and wait for the rest of the country to do their own studies. This work is scheduled for completion in 2024. Meanwhile, that number of 19,000 will grow and there is no agreement between South Australia and the Federal Government as to who funds what and in what timeframe.

Health Minister Chris Picton wrote to us recently and listed off all the investments the Malinauskas Government has made in mental health. We always welcome investment, of course, but what we are not seeing, and what is not being invested in, are services that will keep people out of emergency departments, reduce homelessness and help 19,000 individuals and families.

For all the investments listed by the minister, it is important to understand the government’s solutions will see a third of people back within 28 days.

None of this is going to stop the crisis, sadly it does not even stem the flow.

The SA Mental Health Act says we need “to ensure that persons with severe mental illness receive a comprehensive range of services of the highest standard for their treatment, care and rehabilitation with the goal of bringing about their recovery as far as is possible”.

With this they “retain their freedom, rights, dignity and self‑respect”.

Sadly, on this World Mental Health Day not only are we failing our own Mental Health Act, we are also breaching basic human rights.

Geoff Harris is the executive director of the Mental Health Coalition of South Australia