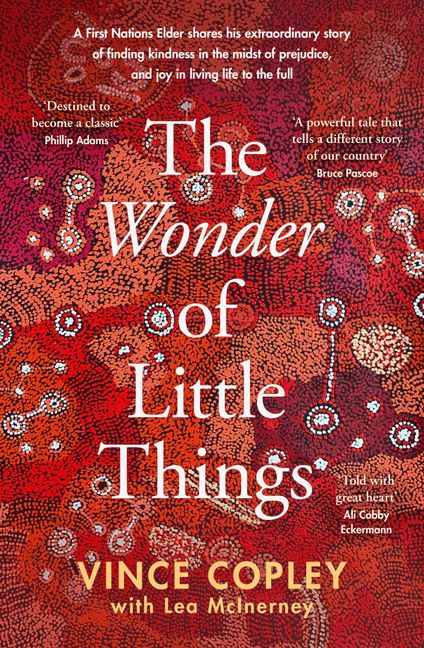

Vince Copley and The Wonder of Little Things

The extraordinary life of an Indigenous South Australian is revealed in a just-published memoir. Sandra Phillips examines the institutional racism encountered, community attitudes and prejudice and his role in progressing Aboriginal rights.

St Francis House at Port Adelaide in 1950, with Vince Copley third from right. Photo supplied

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

In his memoir’s final chapter, Vince Copley wonders: if the first legal marriage of an Aboriginal woman and a white man had been socially accepted in the 1850s, would his own wife have been spared being pushed to the end of the 1970s bank queue because she was with him, a blackfella? Would that real estate agent have considered their application instead of throwing it straight in the bin? Would their daughter have been spared the schoolyard bullying and their son the name-calling?

Copley is descended (through his grandmother Maisie May Edwards, nee Adams) from Kudnarto, the Kaurna woman who married shepherd Thomas Adams on 27 January 1848, in South Australia’s first legal marriage between an Aboriginal woman and a colonist. His ancestral connections included Ngadjuri, Narungga, and Ngarrindjeri.

Readers of The Wonder of Little Things (2022) will find it hard to think of Vince Copley in the past tense. Crafted from oral storytelling of around about 300 recollections, Copley’s voice in this first-person memoir brings you close, almost as if you are sitting at a table with him, drinking his fabled cups of tea.

Vince with Lea McInerney, co-writer of his memoir.

ABC Books, Author provided

A humble man who met kings, queens and heroes

Born on a government mission in 1936, Vince died at home on January 10 2022, aged 85, after the complete manuscript he had prepared with writer Lea McInerney was written and the publisher had despatched questions for final revision. His beloved wife Brenda had passed in 2020 and it was she who had lovingly “bullied” him into telling the story of his life, so their kids would know what he had done.

The book is dedicated to his children, Kara and Vincent. Many generations appear within its covers – the book itself now an important part of family storytelling and knowledge. Lea McInerney is recognised for her dedication to Copley’s voice and vision; Copley said “I’m the storyteller, you’re the writer, and this is our book”.

There were many other pre-publication readers too, all of them thanked in the book’s acknowledgements. Reconstituting this life story was its own winding journey. Copley’s niece Kath’s documenting of that journey through photos and video could be considered as the basis for another form of media about the making of this memoir.

The inclusion of photographs and further reading, including a well-researched timeline of significant events in Australian and Indigenous history, enhances the book’s educational appeal.

But what might you find in The Wonder of Little Things?

A man who met the King of Jordan, the Queen of England and Muhammad Ali; a man of humble origins who travelled the world and whose greatest joy seemed to be returning home and eventually knowing more of his own Country.

Vince Copley at the engraved stone that acknowledges the Ngaduri people as the original custodians of the land, at Sevenhill, near Clare.

Lea McInerney

Towards the end of the book, there is a moment where Copley reads his own Country, standing near an ancient Ngadjuri rock engraving, seeing other sites he’d visited in the distance. It’s told in understated fashion, so it could be easy to miss the significance of this among the other recollections quilted together in the book.

Connection to Country is widely understood to be a key determinant in health and wellbeing; it can also be difficult to maintain. Indeed, this phase in Copley’s life was initiated from a chance encounter with archaeologists!

Riding shotgun through Australian history

Through the prism of Copley’s life story, we ride shotgun on some of the most important moments in Indigenous – and therefore Australian – history. We see the movement of Aboriginal people from missions into towns and cities, and the hardship (but also the opportunities) encountered.

Aboriginal people weren’t allowed to drink or be served in hotels then, but the women found ways to socialise. Vince’s mum married his stepfather in 1942; he recalls “Mum’s photo on the front page of a newspaper called The Truth and that not very nice things had been written about her”.

Some family members applied for and received exemption from the restrictive provisions of the Aborigines Act, which meant less control of their every movement, and was granted to Aboriginal people who were deemed to be “worthy”. (If not exempted, Aboriginal people could not open a bank account, buy land or legally drink alcohol. However, exempted people were not supposed to have contact with non-exempt Aboriginal people any more.) Vince’s mum’s 1946 exemption certificate appears in the book.

Voluntarily living at St Francis House in Adelaide, a boys’ home where Aboriginal kids from remote areas could get an education in the city, was a striking example of the opportunity afforded by urban movement. Much later, in 2014 in the same city, Vince was presented with the Member of the Order of Australia by then-governor of South Australia, Hieu Van Le.

St Francis House boys in 1950, on their way to school. Left to right: Laurie Bray, Desi Price, Kenny Hampton, Richie Bray, Malcolm Cooper, Gordon Briscoe, Ron Tilmouth, Vince Copley, Gerry Hill and Wilf Huddleston.

St Francis House

As a young man, Vince spent time living and working in country towns where the racism took the breath away. (For example, travelling for work to buy a grain elevator, Vince had to leave Wee Waa without the equipment because he could not get a white person to speak to him, let alone give him directions.)

And then there was Curramulka, on South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula, where Vince was recruited to play football, and initially worked as a shearer. He came and went over the years, boarding with a family, the Thomases (whose members included his future wife Brenda), on a farm just outside the town. He lived with the Thomases, “all up”, for 13 or 14 years.

“The Currie” holds a very special place in Vince’s heart: he became his own man here and he experienced a different social life from the one he’d been used to. In the Currie, Vince was invited to dinner at white folks’ homes. He could ask a woman to dance and not be rebuffed. He became coach and captain of the local football team, which he took to premierships in 1957, 1958, and 1950.

Vince Copley, aged 21 (pictured holding the ball, front-row centre) with the Curramulka A Grade Premiers AFL team, in his second year as captain-coach.

Curramulka Community Club

The footy-mad towns of country South Australia found themselves in a dilemma only some of them could overcome: racist stereotyping couldn’t hold itself together if an Aboriginal person could live up close and be seen as fully human. Copley tells us his life, and through it we get to see the fabric of Australian life forming.

Lifelong friendships

Copley tells of a lifelong friendship with Charles Perkins, which began when they were both residents of the St Francis Home for Boys.

There are other St Francis boys he also calls family: academic and activist Gordon Briscoe (the first Indigenous person to be awarded a PhD from an Australian university), John Moriarty (co-owner with wife Ros Moriarty of Balarinji, the design studio that created the Wunala and Nalanji Dreamings painted on two Qantas jumbos and the first Aboriginal player selected to play soccer for Australia), Wilf Huddleton, Richie Bray, Malcolm Cooper, Kenny Hampton, Ron Tilmouth and more.

One of many reunions of the St Francis boys, for Vince’s son VIncent’s baptism in 1976. From left to right: Desi Price, John Moriarty, Charles Perkins, Vince Copley, Mrs Smith, Father Smith (founder of St Francis Home for Boys), Les Nayda and Gordon Briscoe.

Courtesy of the P. McD. Smith MBE and St Francis House Collection

The friendship with Perkins, though, is what shapes much of Copley’s working life through the 1970s, 80s and 90s. Many times, he mentions Charlie would ask him to step in for him when he couldn’t make a meeting, a conference or a trip. Thus, Copley was there at the formation of key organisations and movements in the contemporary Aboriginal world.

These include: rights organisation the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, the National Aboriginal and Islander Liberation Movement, the first federal Department of Aboriginal Affairs, the Aboriginal Development Commission, the National Aboriginal Consultative Committee, Aboriginal Hostels Limited, the inaugural Barunga Festival and the Barunga Bark Petition, the National Aboriginal and Islander Day of Celebration (NAIDOC), inaugural co-chair of Cricket Australia’s National Indigenous Cricket Advisory Council, inaugural chair of Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, and more.

Charles Perkins, fourth from left, on the Freedom Ride in 1965.

Mitchell Library State Library of NSW

It would be a mistake to think Copley’s influence was defined by Perkins: he too had magnetism, his own charisma and intelligence, his own vision for a better Australia and vision for better lives for his own people.

Loss and a long life

It’s hard to see how Vince Copley could have fitted any more into his life, but he does recall in The Wonder of Little Things some regret that he didn’t get to know more about his paternal grandfather Barney Waria. (Warrior in the book, matching Vince’s father, Frederick Warrior – the name was anglicised at some stage).

His memoir deals with the contentious issue of the 30-year embargo on the field notes of anthropologists Catherine and Ronald Berndt, which include information about and from Barney Warrior. As we keep moving into a future of democratised archives and changed power relationships in all aspects of life, one wonders if that embargo created unnecessary missed opportunity and heartache for Vince Copley.

Vincent Copley with his son Vincent Copley junior. They are holding Ngadjuri book, with their grandfather and great-grandfather, Barney Waria, on the cover.

Flinders University

Vince Copley knew loss. His mother died when he was 15 and before that, four other members of his immediate family had also died prematurely, including his beloved big brother, Colin. We meet Colin on the opening page: Vince is four and Colin six years older than him. It’s clear that Vince is in awe of his brother, a “really fast runner”, and by page three (set in “the 1940s”), Colin is dead of an untreated infection from tearing his knee on barbed wire.

“The closest hospital is ten miles away in Maitland, but that’s taboo for us – they don’t take Aboriginal people,” Copley writes. The next-closest hospital is 50 miles away, in Wallaroo, but the family can’t access a car and the quickest route to a hospital is by bus, to Adelaide. When they arrive, “the infection’s set in too far”.

Vince, too, could have died early (at the age of 15) of appendicitis, if not for the third hospital he visited, in Wallaroo, which admitted and treated him after hospitals in Ardrossan and Maitland refused to. Vince writes: “Later they told me that if my appendix had burst, I would have been history.”

From an early sporting and very physical working life, Copley became a bureaucrat in this new and emerging Australia – he was often in cars and planes, sitting in meetings, smoking, and eating out. He attributes his need for open-heart surgery at the age of 45 to that lifestyle, and this proves yet another turning point in the life of this incredibly interesting person, whose humility and passion were hallmarks of a long life, lived well.

While the St Francis boys who as men were central to Copley throughout his life, he also often refers to the strong women in his family – his sisters Josie and Winnie and his Aunty Glad (Aboriginal community leader Gladys Elphick, whose achievements included founding the Council of Aboriginal Women of South Australia and the Aboriginal Medical Service). He is loving about his mother, whose life was cut so cruelly short.

We see a man of his time and we might wonder how he would have managed without his courageous and loyal wife Brenda at home, holding down the fort and raising their beautiful children. But Copley provides a sense of a man who knows the worth of women and who could never deny their strength, intelligence, and significance to the making of the world – to the making of his world.

There is so much story told – and waiting to be read and heard – from the pages of The Wonder of Little Things. It would be a shame for readers to miss out.

Sandra Phillips is Associate Professor of Indigenous Australian Studies, School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Associate Professor Sandra Phillips is guest editing, with Associate Professor Corrinne Sullivan, a special issue of international, peer-reviewed open access journal, Genealogy. Dedicated to Indigenous Auto/Biographies, the call for papers is open until 30 April, 2023.