Richardson: Fairness and folly – the politics of electoral boundaries

The quaint and quintessentially South Australian ritual of trying to make sense of our electoral map highlights the cultural gulf between two different branches of government, writes Tom Richardson.

Steven Marshall casting an early ballot for the 2018 state election. Photo: David Mariuz / AAP

In two years time, the state’s political leaders will be pressing the flesh and hitting the airwaves in a bid to convince you to vote for them.

Their respective parties will be utilising their meticulously accumulated electoral data to hone in on prospective target voters and the issues that could swing their support.

All of which will be instrumental in determining who emerges victorious on March 19, 2022.

Electioneering. Photo: Tracey Nearmy / AAP

But of course, we all know by now that the outcome of that day’s poll will already be largely determined by the fervent deliberations of three relatively low-profile public officials.

Supreme Court Justice Trish Kelly, electoral commissioner Mick Sherry and surveyor-general Michael Burdett comprise the current iteration of the Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission, which since 1991 has been tasked with redrawing the state’s electoral map to best reflect the presumptive will of the people.

The Boundaries Commission is a charming and quintessentially-SA invention.

Its recent mission was dreamt up largely as a response to a 1989 election in which the Liberal Party failed to win government despite a clear statewide mandate – only for it to preside over four of the next six elections in which the Liberals failed to win government in their own right (and mostly at all) despite a clear statewide mandate.

Only after the 2016 review effectively threw the methodology favoured by previous boundaries commissions out the proverbial window (and even then, only after drawing up an initial draft report that more or less preserved the status quo) did the Liberals finally manage to pull off an elusive double that, save for the post-State Bank landslide, they hadn’t managed since 1979: winning both the popular vote and the requisite minimum number of seats to form a government.

All of which might prompt some pause to ponder the case for the continued existence of a body tasked with ensuring that the party with a statewide majority should win enough seats to govern repeatedly overseeing the exact opposite outcome.

Moreover, it’s now entirely academic, since the legal requirement that the party that wins a statewide majority should also win enough seats to govern no longer actually exists.

Steven Marshall in his electorate on polling day. Photo: Morgan Sette / AAP

The Commission met last week to ponder how it should interpret a 2017 legislative change that saw, in bizarre and dramatic circumstances, the so-called “fairness clause” expunged from the state’s constitution act.

The clause itself was widely derided – not least, as InDaily first revealed, by the political scientist who initially proposed it – but the Liberals had long argued that it wasn’t the fairness provision that was flawed, but the fact it had never been properly applied despite successive reviews.

Adding insult to injury, those successive reviews instead tended to instead point out that it wasn’t the Commission’s responsibility to teach the Opposition how to campaign properly.

The 2016 Commission – and 2018 election result – proved a powerful rebuttal by Liberal loyalists that the problem all along was not them, but the system.

The truth, as in most things, is more nuanced than either proposition.

But, given Labor has long enjoyed quoting the repeated refrain of successive inquiries that the Commission “can accept no responsibility for the quality of the candidates, policies and campaigns”, it’s worth noting the clearest indication that the ALP attributes a goodly part of its recent electoral success to favourable boundaries.

Namely, the fervour with which it has sought to have them reinstated.

If ALP insiders truly believed their 16 years of power was solely down to their organisational heft and campaigning brilliance, they wouldn’t have bothered challenging the 2016 redistribution in the Supreme Court.

They wouldn’t have worried about trying to engineer legislative change to recognise the primacy of the ‘one vote, one value’ principle, which ensures every electoral district contains roughly the same number of voters but also (just incidentally, of course) tends to lock up a large number of Liberal votes in a relatively few number of safe rural seats.

Nor would Labor have instead enthusiastically embraced a Greens amendment that saw the fairness clause scrapped without recourse to a referendum.

And it wouldn’t have asserted to the Commission this month that that amendment should thus ensure ‘One Vote, One Value’ is the main game in the forthcoming redraw, nor that the existing boundaries on which it fought – and lost – the 2018 poll need substantial redrafting.

If ALP powerbrokers were truly confident that it was Labor that won those four elections, rather than favourable boundaries, none of that would have happened.

The laws that dictate how your vote is counted are made by those who want your vote

For something so notionally important though, there is something inherently comical about the Boundaries Commission.

And not just because it was formed to ensure electoral fairness, and consistently failed to ensure electoral fairness, and now no longer has to consider electoral fairness anyway.

No, the funny thing about the Boundaries Commission is that it spends so much time assigning profound wisdom to the silliness of politicians.

It’s always quite amusing hearing courts try to interpret the laws being made for them by parliament as though parliamentarians are themselves fully cognisant of what they are doing.

It reflects the significant cultural gulf between the legislative and judicial arms of government.

Lawyers are inherently meticulous, whereas parliamentarians voting on laws are frequently confused, following the herd or simply opportunistic.

Last Tuesday, I sat through the best part of 90 minutes as the counsel assisting the Commission, Tom Besanko, made his opening summation of what parliament might have intended when it removed the fairness provision in 2017.

But the thing is, I spoke to plenty of parliamentarians at the time, and most of them didn’t know what they intended.

The substance of the Bill went through in a rush after being moved as a Greens amendment a few hours earlier: no-one really knew what impact it would have. They still don’t.

Labor, of course, just wanted to kill the clause they thought was going to cost them the election.

Greens MLC Mark Parnell, who drafted the amendment, simply considers the fairness provision an impossible aspiration and a relic of a “two-party view of the world” that no longer exists. As Mandy Rice-Davies might say: Well, he would, wouldn’t he?

And the poor old Libs, who at the time knew they were finally on the brink of a new electoral promised land after 16 years of failure, just wanted everything back the way it was.

The anger and desperation exhibited by the normally unflappable Rob Lucas during that 2017 debate might give some indication of the depth of feeling.

But at the end of the day, it was all about self-interest.

Loading…

And now we will have 12 months in which three relatively low-profile public officials and a bunch of lawyers methodically and po-facedly pore over an amendment that was drafted, moved and passed within the space of a week – and which hardly anyone who passed it even understood – and try to assign it some grander motive and meaning.

Was it meant to mean that the statewide vote should no longer be given primacy?

Or that the Commission should instead favour equality of numbers in electoral districts as its over-riding objective?

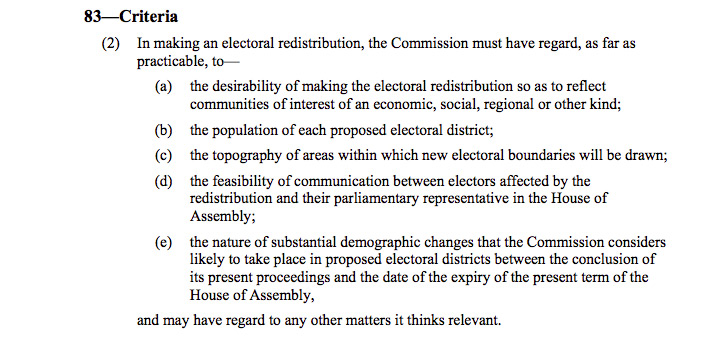

Or moreover, any of the following bits of the Act’s criteria for electoral redistributions that survived the constitutional cull:

The key phrase in the above, of course, is: “Any other matters [the Commission] thinks relevant.”

This appears to cover a wealth of criteria, including – according to Besanko – the now-dumped electoral fairness aspiration itself.

Of course, what a Commission considers relevant is a fundamentally subjective exercise.

What we do know is that both major parties will spend a large chunk of the next 12 months trying to convince Kelly, Sherry and Burdett that the thing they should consider most relevant is the thing that is most likely to see them elected.

Which emphasises a self-evident but disturbing truth: the laws that dictate how your vote is counted are made by those who want your vote.

All of which means by the time you go to cast that vote in a bit over two years’ time, a large part of your decision will probably have been made for you already. One way or another.

So that’s a relief, isn’t it?

Tom Richardson is a senior reporter at InDaily.