Is there enough Adelaide in the Adelaide Festival?

Does the Adelaide Festival do enough for local artists and companies? What does it mean to people on the outskirts of corporate SA? Who does it benefit, really? Stephen Orr asks some troublesome questions.

Wasn't Light's vision about more than buildings?

As you know, I’m hardly the type to cause a stir, offend the small Dad’s Army-style battalion of politicians we’ve managed to muster in this state. Given, I read Orwell, Chomsky, Vidal and all of those, you know, troublemakers. But I’m not one of them.

I’ve never complained about South Australian publisher, Wakefield, being defunded in favour of more under-twelves perfecting the perfect drop punt; I certainly would never complain about the Gilles Plains Primary-style school closures and amalgamations, the lack of twenty-first-century public transport, crumbling roads, gushing water pipes – all of that talkback stuff. But I did find someone, a man named Neville Grave, who had, I think, some valid concerns about the Adelaide Festival.

Here’s a question: has the Adelaide Festival – conceived as a heart-starter for a country town whose wealth derived from agriculture and the first stirrings of Playford’s industrial economy – actually become a contraceptive to the creation of original, local, back-streets-of-Brompton art? Inasmuch as all of the attention, the government money, the media, is focused on a few weeks in March, to the exclusion of other times, other people, other places.

Does this really just suit a government obsessed with the big ticket, the photo op, the launches, the corporate smooching? And what has all of this got to do with the small theatre companies, the Willunga potteries, the Davoren Park poets?

I’m just sayin’. And maybe I’m wrong. But isn’t it time to at least have a conversation? About what John Bishop and Lloyd Dumas were thinking? The idea being to bring the best from around the world, showcase it in Adelaide. Yes, the Festival gave us the title of “Festival State” when other states didn’t have one; it led to the development of infrastructure (Adelaide Festival Centre), higher education arts courses, a more sophisticated gastronomy, aesthetic, nuanced world view, all of these things. And for all of this, we have those late fifties visionaries to thank. But what about today? Is it fair to say the Festival is stuck in its own mindset?

What do we value? Who are our great performers, musicians, composers? Were they asked to the Festival, celebrated, valued?

The big Festival, Edinburgh, is attracting its own chorus of critics, locals who have seen the Old Town gentrified into what Edinburgh producer, artist and film-maker Bonnie Prince Bob call’s “the world’s biggest PR exercise”. He reckons “the Edinburgh Festival has got fuck all to do with the people of Edinburgh”. And maybe he’s right? And maybe this is my gripe too?

As Bob explains: “Let us bathe in the statistics of another bumper year of ticket sales. More shows, more performers, more revenue. More revenue for who? Who benefits?” Certainly not the locals, living fifty clicks from the Royal Mile. “Edinburgh is a physical schism of inequality. For many residents, a day trip into town is an economic absurdity. The Festival is a battleground for big business.” And worse: “A handful of large companies scoop up the majority of sales. They occupy swathes of prime turf where they construct liquid lounges for the consumption of overpriced pints of pish.” Sound familiar?

I meet Neville at the front bar of the Rose and Crown, Elizabeth, during this year’s Festival. He tells me he was a boilermaker for 38 years, and what was I, and I say “a writer”, and he looks at me and says, “Do tell”. So I tell, and he starts on the Festival. “What’s in it for someone like me?” And I think and think and say, “Nothing”. He says, “Exactly”, and pats his Pekinese, Fi-Fi, who’s asleep at his feet (apparently the publican doesn’t mind).

This gets me thinking. What if Neville is right? What if the Festival is for the few? What if it’s now part of some leftover cultural cringe where locals, assuming anything familiar is shit, save all their money for a sneak peek at Kosky’s latest? What if the AF actually detracts from our understanding of ourselves, our aspirations, our dreams, our imaginings? What if all the government money thrown at the top end might be better used at the low-to-middle creative end?

These questions go round and round my head. But I say to Neville, “The Magic Flute, one of Mozart’s masterworks, and C Reserve is only $149″ He almost chokes on his beer, explaining his troubles paying power, water, gas, food, in our brave new privatised dystopia of government for the happy few, and connected.

I drive home from my morning trolley-collecting for the Unemployed Teachers’ Collective. I think, What is the point of a festival? I know the official line: that our loving leaders bring us the best in world culture. You know, cutting edge, risky, not-for-the-faint-hearted sort of stuff. True, but if you can afford $289 for a Premium ticket to The Magic Flute maybe you can afford to see it at the Komische Oper, Berlin (just off Unter den Linden, I went there once, in my pre-trolley days)? Either way, what about Neville, his 19-year-old son (who collects trolleys with me), his wife with back pain and arthritis?

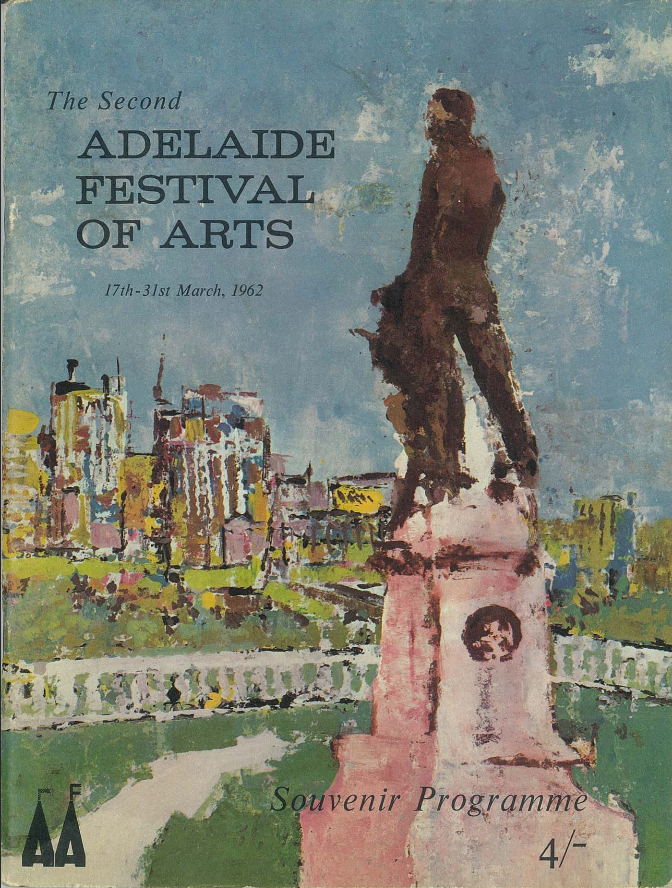

So I arrive home, remember my old copy of the 1962 Festival of Arts Souvenir Programme (4/-) and sit down to think about Neville’s words. I look at the list of operas: Ariadne auf Naxos, La Trav. The plays: Saint Joan, J.B., Volpone. The music: Britten’s version of the flood, a touch of the exotic with Bhaskar and Company’s Dances of India, the London Philharmonic.

I get this. I mean, we, all of us, in 1962, could hardly afford to roam the planet in search of proper stuff. You know … professional stuff. And, I mean, we had fireworks for the Rose and Crown mob, a frock from Miller Anderson, because everyone knew (and knows) it’s “essential to look your loveliest” when stepping out with the London Phil. A Barossa Riesling, the aristocrat of table wines, if not West End from the Rose’s couplings. But things have changed, haven’t they? Don’t we train our own creative types now, encourage them? Don’t we? We don’t need to pretend ex-Adelaideans are the only good ones.

I get this. I mean, we, all of us, in 1962, could hardly afford to roam the planet in search of proper stuff. You know … professional stuff. And, I mean, we had fireworks for the Rose and Crown mob, a frock from Miller Anderson, because everyone knew (and knows) it’s “essential to look your loveliest” when stepping out with the London Phil. A Barossa Riesling, the aristocrat of table wines, if not West End from the Rose’s couplings. But things have changed, haven’t they? Don’t we train our own creative types now, encourage them? Don’t we? We don’t need to pretend ex-Adelaideans are the only good ones.

Anyway, that was so long ago, and things have changed. I mean, imagine this – a festival director programming a local opera, already written, scored, arranged, a once-in-a-lifetime chance for us to create something great. Or maybe just another Wendt’s Exhibition of Diamonds and Replicas of the Crown Jewels? In fact, what are our crown jewels? What do we value? Who are our great performers, musicians, composers? Were they asked to the Festival, celebrated, valued?

I, Trolley Boy of the North, have seen too many good people go to waste. I’ve seen them give up, unacknowledged, or go overseas with the shows they’ve written, interstate with the books they’ve published, bigger, better, prouder, smarter cities that have made them welcome and given them opportunities. But there, on the cover of the programme of our second festival, a painting of a grainy Will Light looking across his low-rise city – and I thought, wasn’t the Vison about more than buildings?

I have a lot of time, roaming the carpark at Coles in my hi-vis, wondering what sort of people we South Australians really are, what we value, and what we want to pass on to our kids.

I remember saying to Neville: “At least we’ve got the Fringe. Something the average bloke can get his teeth into.” He agreed. “I love the guy who dresses up like a German sheila.” That, he explained, at least got you laughing. Because it was important, he said, that people didn’t agree on everything, and that there was a little bit of conflict, not just fake jewels and Riesling.

No-one’s saying we should get rid of the Festival, but we need to remember that culture is more than commerce. It’s also about the little guys, the quiet voices, the Christies Beach plumbers. Or do we really want to end up like Edinburgh where, according to Bonnie Prince Bob: “It’s not something by Edinburgh, it is something done to Edinburgh.” A battleground for big business, where “corporate apologists paid handsomely to market the event globally and deflect… from the increasingly legitimate complaints as to its actual benefit or purpose.”

Time will tell. But the food vans are circling, and the Pimm’s is getting pricey.

Stephen Orr is an Adelaide writer. His latest novel, This Excellent Machine, is a coming-of-age novel in the most fibro tradition.