Flawed jury process stacked the witness list

The failed process of the nuclear fuel cycle citizens’ jury could lead to an economic tragedy for South Australia, argues Ben Heard.

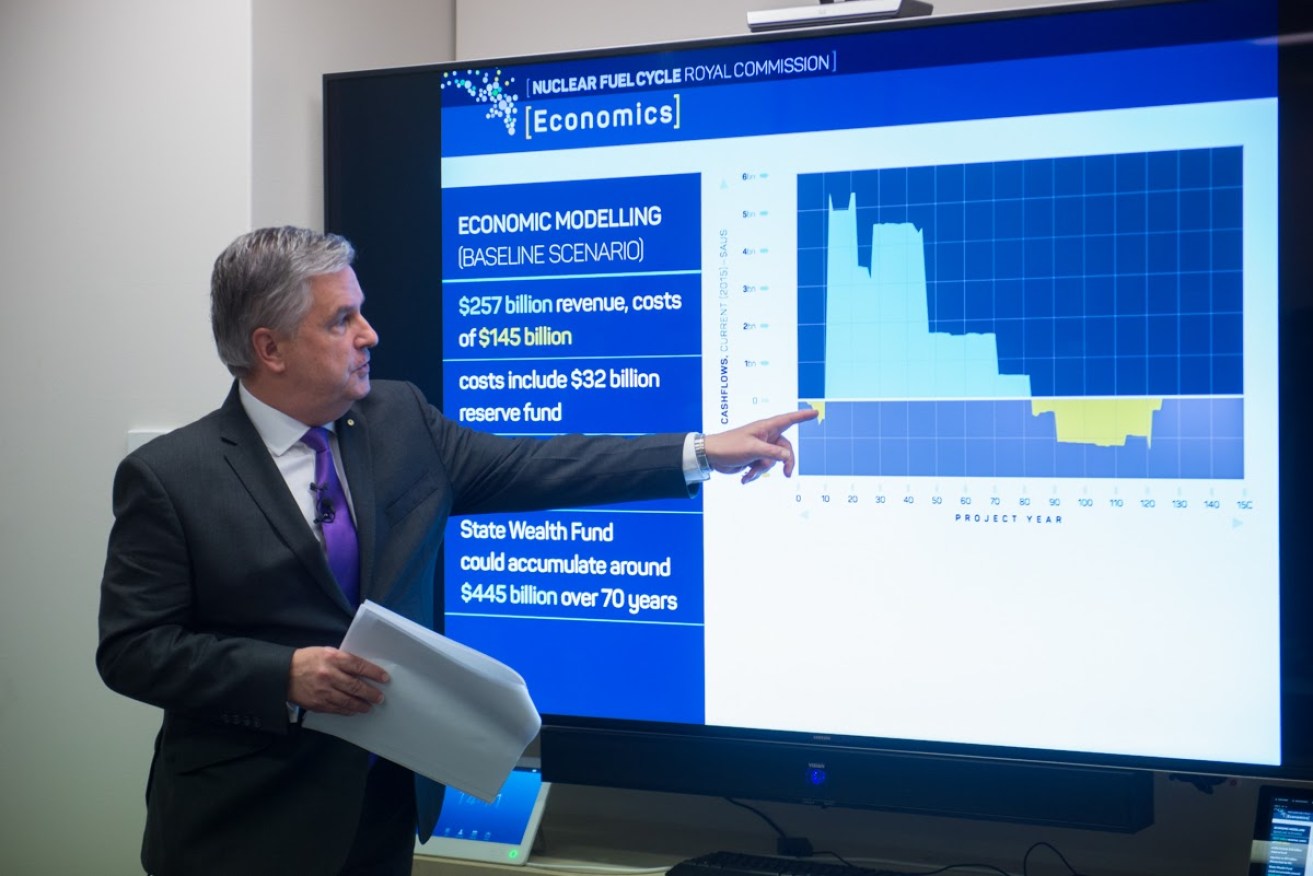

Nuclear Royal Commissioner Kevin Scarce explaining his economic modelling to the media - not the citizens' jury. Photo: Nat Rogers, InDaily.

Knowing someone is an economist is like knowing someone is a scientist. It speaks of an overall discipline and qualification, not of relevant knowledge, experience and competence in a particular specialisation. In reviewing the process of the nuclear citizens’ jury, Richard Blandy paints a picture of experts tackling amateur work. Nothing could be further from the truth.

As Blandy pointed out, all the economics witnesses who addressed the jury opposed the royal commission’s proposal relating to used nuclear fuel. Yet none are experts in that specific area. Professor Blandy’s reputation is as a labour market economist and his work in the 1980s, as head of the National Institute of Labour Studies at Flinders University, played a big role in advancing arguments for enterprise bargaining. However, he is not a resource economist let alone someone with a track record publishing on the economics of the nuclear fuel cycle.

I would argue his testimony to the jury demonstrates this absence of track record. Indeed, his earlier submissions to the royal commission, which were placed before a panel of eminent professors for review, gained no traction, in my view. This lack of specialized knowledge is true of all the witnesses (Diesendorf, Pocock and Dennis) who addressed the jury that day. The stinging minority report from fully 30 per cent of the jurors highlighted that each and every economics speaker “clearly had a negative view of the industry”. Yet Blandy claims this jury “refused to be dazzled”.

Readers might well wonder what type of witness list only includes witnesses only from the prosecution. In an inversion of process, witnesses were chosen by the jury. Juries never choose witnesses because confirmation bias is a reality of critical thought. By handing witness selection to the jury, rather than prosecution and defence as it were, you get a confirmation bias cascade. The resulting bloc of economic objectors brought much doubt and no insight, with a lone representative consultant left defending their work.

Blandy acknowledges it was only through the intervention of the organisers that the actual lead author of the report was even there! The jury would have happily heard only from ardent critics. This reeks of a failure of process. The organisers must take responsibility for these ridiculous circumstances.

The work in question by Jacobs MCM was won in competitive global tender at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars. It is now the most comprehensive insight available into this potential market. I know this as I am a full-time researcher in this area, with an upcoming journal paper comparing my approach to that of Jacobs MCM. As well as a team of seven authors, the work was peer-reviewed by a panel of eminent scholars and economists: Professor Mike Young (University of Adelaide); Professor Sue Richardson (Flinders University); Professor Paul Kerin (Head of Economics, University of Adelaide); Professor Ken Baldwin (Australian National University); Professor Quentin Grafton (UNESCO).

So when Blandy cites Pocock as saying “all the economist agreed the dump was not a goer”, that isn’t a correct picture. The analysis was prepared by economists and industry experts, reviewed by economists and industry experts. The bloc on the day raised their own uncertainties, presented it (erroneously) as representative of the broader state of knowledge and effectively undermined the professional work.

The economic case available from the royal commission has provided an essential starting point; it begs the question, why not ‘test the assumptions’?

One example brought to my attention by a juror was the attempt by the Australia Institute’s Richard Dennis to compare what might be the future market for used nuclear fuel to the vagaries of the oil market. This is a demonstrably flawed analogy. In oil, production is in the millions of barrels per day. What comes out of the ground is relatively close to the end product. A strategic domestic oil reserve is measured in 60 days of supply and Australia only holds 30 days of supply. When the price of oil changes the whole world feels it because the commodity is very close to the end product and we are totally dependent on it.

Nuclear fuel is a precision value-added product that bears no resemblance to resource commodities like oil or even mined uranium.

A single fuel assembly (picture a milk crate, but 3m tall) provides two years’ worth of operations to a reactor. Operators can and do readily stockpile nuclear fuel, one of the appeals of nuclear power. So what does the volatile oil market have to do with the economics of used nuclear fuel? Nothing. The comparison was invalid. It would have been contested were this panel externally selected for expertise and balance rather than internally selected for “what we think we want to hear”.

When addressing to the jurors (all online here) Blandy, like Dennis, relies more on asking rhetorical questions than testing propositions. This example is a stand out:

“Would no other country enter the market if there was a bonanza happening in South Australia? …If the project were likely to make so much money, why wouldn’t BHP be wanting to invest in it, or at least spend the next $10 million to explore the project further?”

That Blandy and Dennis have obvious questions and no answers demonstrates to me that they are unqualified to comment. The used fuel service is not something just anyone can offer. Nations will not send their material to just any nation. Australia is probably the single best-positioned nation to deliver this service, a point that is repeatedly driven home to me when I raise the prospect with relevant stakeholders around the world. It will likely take a decade of planning, contracts, international agreements, legislating involving governments in Australia, other nations, our regulator, our safeguards and non-proliferation office, and time developing the needed infrastructure. The idea that, say, Azerbaijan or whoever will just suddenly undercut us is entirely absurd.

Every step we take would reinforce our position. If anything, the barriers to entry are so high that once we are established as the default supplier of this service no other nation would get started for many decades to come. That, by the way, was the precise economic reasoning in the royal commission report against pursuing new industry in enrichment and fabrication: the market demand is now met and the barriers to entry are high. In those cases the conclusions were met with furious agreement by nuclear opponents.

The economic case needs more work and greater consideration, and it needs the State Government, with support from the Opposition to go one gentle step future, namely to test the economic model put to the royal commission. This involves directly finding out what price interested nations would pay per tonne of used fuel, what volume they have to send, and whether they are willing to ‘pre-commit, that is pay up front. The third point is vital as the state cannot afford to go into debt to build a repository.

The economic case available from the royal commission has provided an essential starting point; it begs the question, why not ‘test the assumptions’? In my testimony to the Joint Committee I highlighted the importance of considering of a greater range of commercial models to service a market need that is indisputably present. Blandy and his allies may be right, but they have no foundation to rest their case with any certainty. Certainty will only arrive with the government sticking the course and approaching potential customers. Not to do so on the basis of a citizens’ jury process that so demonstrably failed to create anything like a ‘courtroom’ would be a tragedy for the economics prospects of our state.

Ben Heard is a doctoral student at the University of Adelaide focusing on clean energy systems and the nuclear fuel cycle. His new paper, ‘Closing the cycle: How Australia and Asia can reinvent the back end of the nuclear fuel cycle’, will be published soon.