No, Festival Plaza will not be Adelaide’s ‘Federation Square’

The drawn-out saga of Adelaide’s Festival Plaza has finally reached its end game, with taxpayers in the dark about whether they’ve received a good deal or not.

An image released by the State Government of the two shining Walker Corporation buildings towering over Parliament House.

After more than a decade of secret and poorly managed negotiations, the state government has finally given giant development company Walker Corporation what it wanted all along: two giant towers on the city’s most prime public land.

This saga has tested the patience of the South Australian public, who have waited years for the entire Festival Plaza to be reopened to general use and will now have to wait years more.

The process began 12 years ago – the latest high rise isn’t expected to be completed until mid-2027 at the earliest.

But the ludicrous amount of time taken to come to some sort of resolution on a key public place in Adelaide is far from the biggest concern.

Even if you believe the government rhetoric about Adelaide “growing up” and the building being a show of confidence in South Australia, the process involved here has been a travesty of public administration.

What a strange journey it has been to reach this point, where office blocks on public land are presented as some sort of generational transformation of the city.

Rhetoric from both major political parties about the plaza becoming Adelaide’s version of Melbourne’s Federation Square is revealing.

Fed Square is an open plaza surrounded by a mix of attractive cultural institutions and relevant enterprises, including the Ian Potter Centre, which houses the National Gallery of Victoria’s impressive Australian collection, SBS, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, and the Koorie Heritage Trust, to name a few. It was masterplanned in the public interest – not carved up in the interests of a single private developer.

It took eight years from the announcement of the concept to the opening of the square in October 2002.

The Festival Plaza process will run to at least 15 years by the time the second Walker tower is completed and the resulting plaza will be nothing like Fed Square in scope or content.

It’s a result born of dithering, inadequate processes and a hardball developer who wouldn’t take no for an answer.

Melbourne’s Federation Square, which is fringed with major cultural institutions. Photo: AAP/Daniel Pockett

The original deal was a sweet one, but the negotiations were rocky and the timeline complicated.

Suffice it to say, the Walker Corporation agreed to contribute $40 million to the redevelopment of the plaza in return for rights to rebuild and run the car park underneath.

The government immediately leased back hundreds of car parks, paying Walker $30 million up-front for the privilege. Sweet.

The saga began in 2012, when Walker won a competitive process for a “request for proposal” encompassing the car park, plaza and a “retail or cultural building”.

In 2013, a tender evaluation panel recommended the Walker proposal be rejected.

A few months later, the government began direct and exclusive negotiations with Walker.

Before the 2014 election, then Premier Jay Weatherill declared “we won’t be having a 13-storey building on the plaza area”.

In 2017, his government signed an agreement for the car park, plaza redevelopment and a huge office building. That building – the 29-storey One Festival Tower – was opened recently.

The Marshall Government agreed to an additional three-storey building behind Parliament House, but the new Labor Government favoured a shift to an even bigger high rise than the first tower, confirmed last week.

The timeline seems odd doesn’t it? The Auditor-General agrees.

In a scathing 2017 report, the state’s financial probity watchdog found an extraordinarily long list of problems with the original process: lack of transparency and documentation; no financial analysis on key parts of the deal (like the $30 million car park lease); no effective governance structure; no compliance with mandated planning, evaluation, approval and procurement frameworks.

There were conflict of interest shortcomings. An engineering firm subcontracted by the government to provide engineering advice on the precinct plan was also engaged by Walker Corporation to provide engineering services. The government never identified the potential conflict. The auditor has no idea whether the risks associated with the relationship were assessed or addressed.

Other damning details have come through hard-won FOI battles with the government.

In 2015, then Greens MLC Mark Parnell gained access to Walker’s original plans for the plaza – after a long fight – which showed buildings plastered all over the public space.

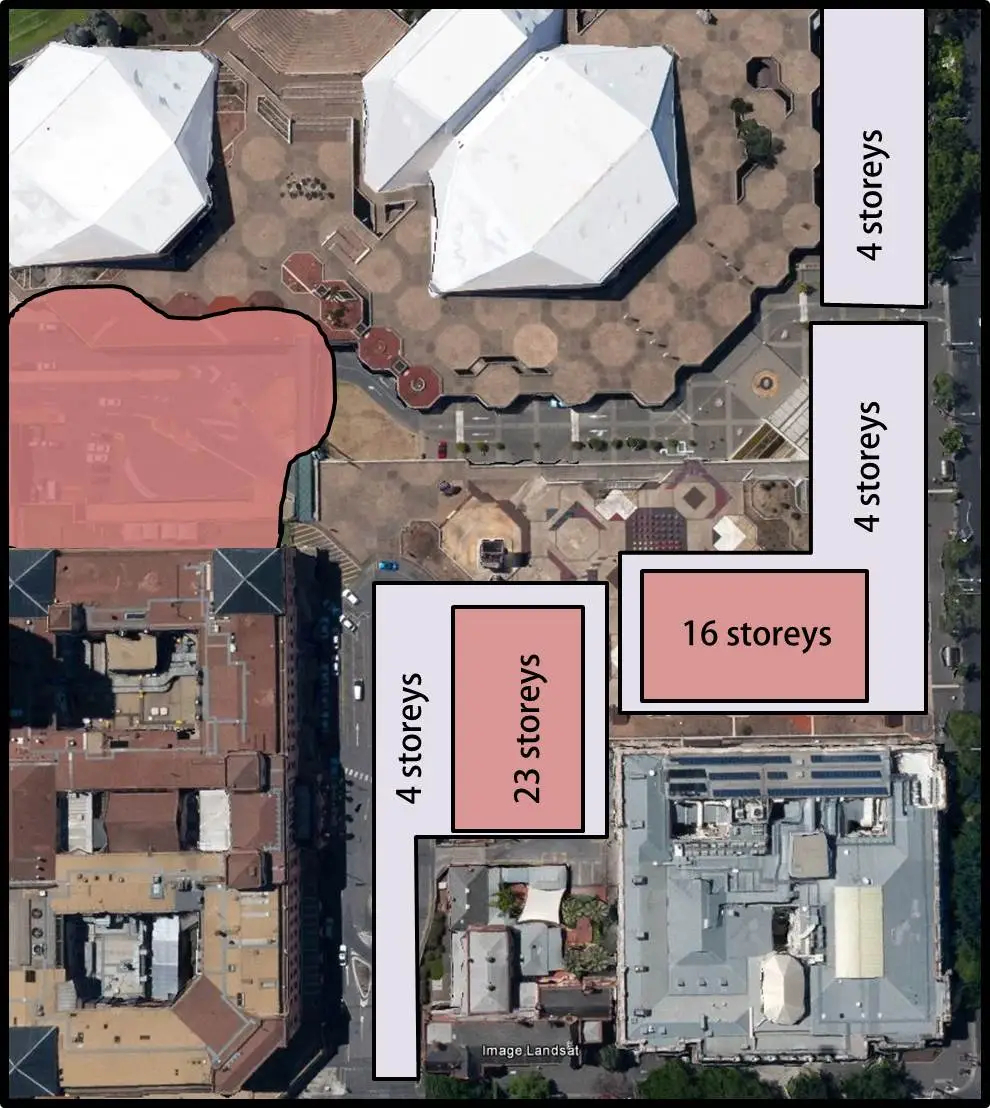

As well as a 23-storey building where the One Festival Tower now stands, Walker wanted a 16-storey high rise behind Parliament House, four-storey buildings along King William Street, and a four-storey development along the lane facing the casino.

The plans were opposed – understandably – by the then Premier Jay Weatherill and the Adelaide Festival Centre. Yet, today, Walker Corporation have ended up with two high-rise buildings, much taller than anything in their original pitch.

Like the first deal, the government says the taxpayer is getting $40 million of value back from the new tower, which will include some “civic space”.

What that actually means is yet to be seen.

Walker’s original plans for the plaza, as reconstructed by Mark Parnell’s office in 2015 because the original illustrations were deemed to be under copyright.

There’s no doubt the new towers will bring more people to the plaza, but that seems a small return on investment. As the Auditor-General has indicated, we have no idea whether this is a good deal or not.

These shining new office blocks will certainly be icons of the skyline.

But if they are emblems of anything, it is the failure of successive governments to see any value in building a cultural precinct in the most obvious place in the city.

Sadly, it’s not hard to perceive the long shadow of the State Bank disaster: this whole episode began with a mindset of paucity, where even a relatively small private contribution to a public project made a paltry deal seem palatable to a cash-starved government.

Adelaide desperately needs high-quality privately-funded development, but the way this deal was forged is likely to damage public confidence in the government’s capacity to represent their interests, particularly when public land and money is at stake.

Notes on Adelaide is a weekly column reflecting on the city, its strengths and its foibles. You can read more Notes on Adelaide in SALIFE’s print editions.