Fish return to Coorong after River Murray’s salt-flushing flood

As thousands of dead carp and bony bream continue washing up on Fleurieu Peninsula beaches, new life is appearing in the Coorong and Lower Lakes with River Murray flooding flushing out water once too salty for fish to survive. Watch the video

Thousands of dead fish washed onto Middleton Beach in February. Photo: Sam Hosking

Scientists are netting Coorong Mullet and baby garfish high in the system, after floodwaters surging down the River Murray since December scoured open its sand-clogged mouth to push fresh water into the long-suffering region.

Salinity levels in Lake Albert have been halved by the arrival of fresh water, reinvigorating a system that has been suffering since the Millennium Drought in 2001 until 2009, according to the Environment and Water Department’s Adrienne Rumbelow .

Lake Albert salinity levels have dropped from 1800 electrical conductivity units about 12 months ago to what is now deemed fresh water at 800-900 EC.

Rumbelow is now hopeful the lake will soon see nationally threatened species like the Murray Hardyhead fish return to the fragile eco-system she has been monitoring since 2003.

“And there’s been a really good fish response in the Coorong, the southern part has been pretty uninhabitable for most species … it’s been a lot more salty than the sea,” Rumbelow, DEW’s Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth leader, says.

Drought and ongoing low river flows meant the Coorong was so salty that even fresh sea water now flowing from the Murray Mouth at Goolwa is helping reinvigorate the system.

“Now we are getting all those species moving down and they are really increasing their range,” Rumbelow says.

Among the fish are black bream not seen in the Coorong since the drought along with Congoli, a little fish growing to 30cm that needs both fresh and salt water to survive, plus bait species like the smallmouthed hardyhead and sandy sprat.

[solstice_jwplayer mediaid=”8vT3br3n” title=”Fish monitoring by SARDI Aquatic Sciences at Salt Creek, with flows from Salt Creek to the southern Coorong. Footage: DEW/Extreme Beyond” /]

It means fish-eating birds like iconic pelicans are also breeding in large numbers at Australia’s largest breeding rookery in the Coorong South lagoon, while black swans are thriving throughout the Ramsar-listed wetlands.

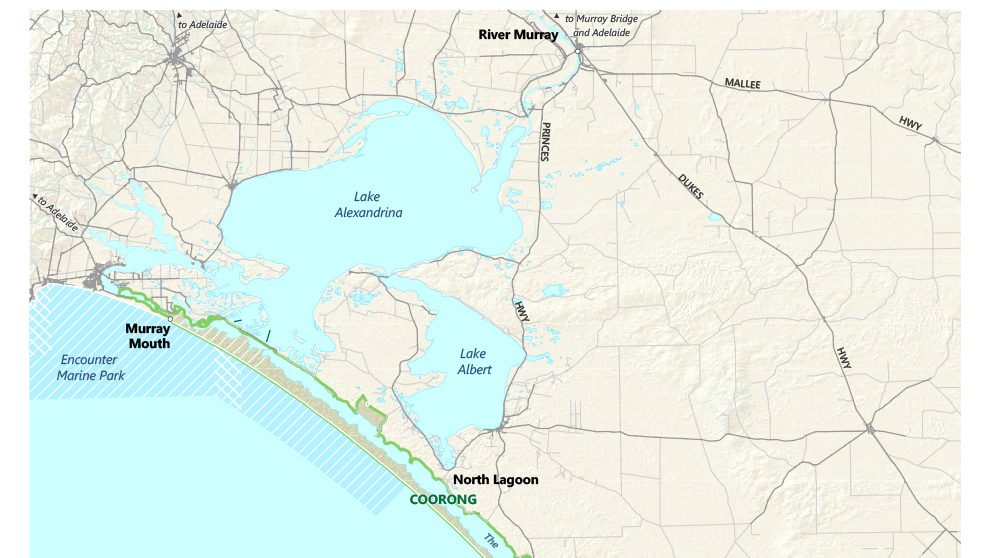

Rumbelow has spent 20 years monitoring the Lower Lakes and Coorong that starts where the River Murray meets the Southern Ocean, stretching around 200 kilometres to Kingston in the south-east.

She saw the Lower Lakes begin to dry up and the Murray Mouth close leading to around-the-clock dredging during the Millennium Drought – many native plants and animals no longer able to survive in the Coorong after it turned five times saltier than the sea.

It was on December 23 last year that River Murray floodwaters surging over the Victorian border into South Australia peaked at it highest level since 1956 at 190GL a day, moving down the system to reach the Murray Mouth weeks later. Latest data shows flows are now around 27GL a day at the border.

High flows saw dredgers working to keep the Murray Mouth open being stood down for the first time in years. Apart from a few months off during the 2016 high river flow, the dredgers have been operating at the mouth since 2015.

SA Water confirmed dredgers are still out of action as sand build up and flow is continually assessed.

Rumbelow is hopeful that the fortunes of thousands of vulnerable migratory wading birds that struggled with River Murray flooding covering important Coorong feeding wetlands during Summer will also change next year.

Few Curlew Sandpipers were spotted at the internationally significant bird sanctuary as there were no exposed mudflats to feed, and rising water flooded rocky breeding areas washing away eggs and chicks from nesting fairy terns.

When the terns moved their nests closer to the Murray Mouth, Rumbelow says “they were picked off by ravens”.

Curlew sandpiper at Mundoo Island Station. Photo: Sally Grundy, Mundoo Island Station.

Thousands of dead mainly carp and bony bream also began washing up on popular holiday beaches at Goolwa and Middleton around January, the fresh water fish killed by salt water as they were flung into the ocean through the River Murray mouth.

A CSIRO study is now underway to sample water and monitor the impact of the biomass of dead fish on the ecosystem.

The floods also led to five barrages around the River Murray Mouth, including one built in 1940 at Goolwa, being opened for the first time in decades to release surging water into the ocean.

This series of 576 operational barrage bays at Goolwa, Mundoo, Boundary Creek, Ewe Island and Tauwitchere have been since manually closed by SA Water crews as river levels return to normal.

At Mundoo Island Station, joint owner Sally Grundy was this week helping Adelaide University scientist Dr Scotte Wederburn set nets at four sites to monitor fish species over March at the property – the last along the River Murray.

They are hoping the flood waters that covered expanses of the station’s around 3230ha of grazing land for Angus cattle and Dorper sheep will now help numbers of endangered Southern pygmy perch fish and Southern bell frog recover.

Billabongs and wetlands are full to the brim on the station that encompasses a series of islands in the mouth of the River Murray with Mundoo Island the largest at about 1,200ha.

It has a unique ecosystem impacted by the River Murray flood. On one side of the islands is the salt water of the Coorong while the other side is lapped by fresh River Murray water.

Sally Grundy, who owns the stations with husband Colin, is a keen environmental photographer and is committed to counting bird, fish and frog species in surveys for Bird Life Australia, government and universities particularly after “the drought absolutely rolled the environment”.

She for one is feeling positive about the future after the station managed to get through flooding relatively unscathed.

“I think everything will recover beautifully and we’ll have a much more invigorated Coorong and river environment,” she says: “Everything will flourish.”