‘Stone by stone’: Inside the painstaking relocation of the Urrbrae gatehouse

Painstaking documentation, meticulous measurements and an inverted building process – this is the inside story of how the state heritage-listed Urrbrae gatehouse was “carefully demolished” in preparation for its reconstruction. See the timelapse videos

The Urrbrae gatehouse before it was dismantled, one stone at a time, in March 2022. Left photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily; right photo: DIT/supplied

After more than 130 years standing in place, the Waite gatehouse on the corner of Cross Road and Fullarton Road was last year dismantled. Hundreds of individually marked stone pieces were sent away on trucks to make way for a road-widening project.

By the end of 2023, the state heritage-listed structure – built in 1890 and linked to the University of Adelaide’s Urrbrae House historic precinct – will respawn hundreds of metres away with a new rear extension and renovated interior.

More than 15 different trades are involved in the painstaking process of reconstructing the gatehouse and restoring it to something like its former glory.

InDaily sat down with Paul Glassenbury – sole director and manager of G-Force Building and Consulting, the lead contractor on the project – and Michael Rander – delivery manager at the Department for Infrastructure and Transport – to find out how the restoration is progressing.

How to ‘carefully demolish’ a 130-year-old building

Video: Department for Infrastructure and Transport

The status of the gatehouse became the subject of significant public debate in December 2020 when the Marshall Government announced it would bulldoze the entire building to make way for a $61 million intersection upgrade.

The decision came despite the state government receiving engineering advice that relocating the gatehouse was feasible.

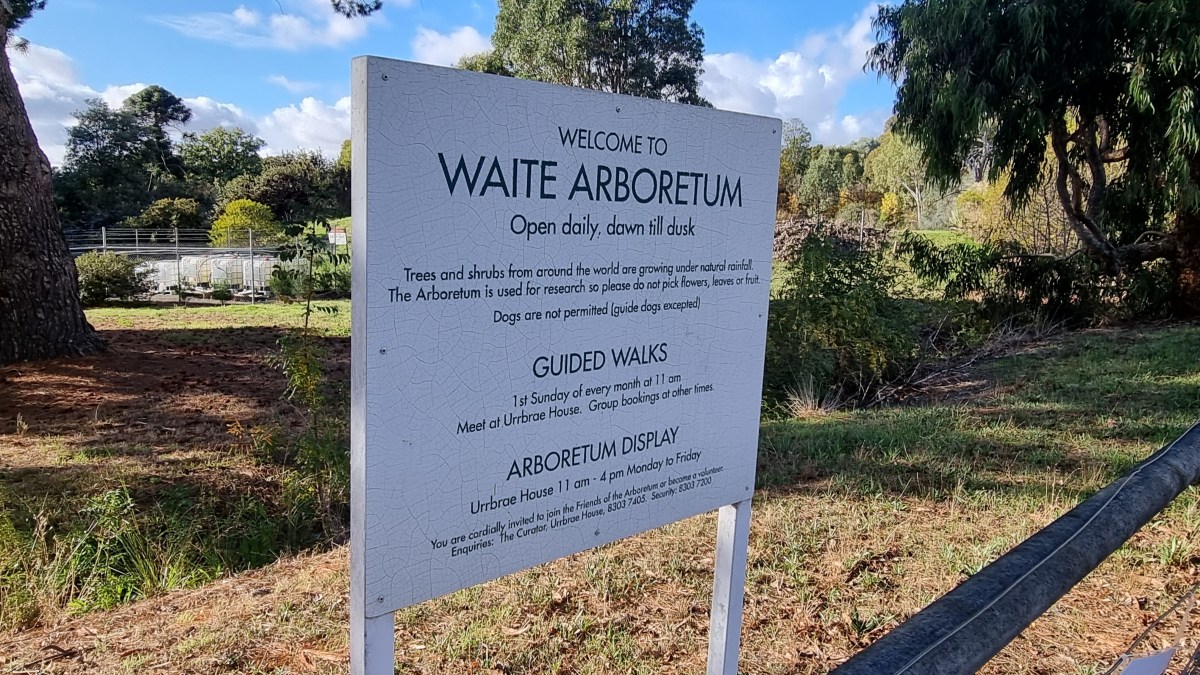

Numerous heritage and building movement experts subsequently came forward with their belief the gatehouse could be moved safely and, following months of pressure from heritage groups, the University of Adelaide and members of the public, the government opted to instead move the building to the southeastern side of the Waite Arboretum.

The Department then drew up plans to “carefully demolish” the gatehouse, salvage its materials for reuse and rebuild it into a volunteer centre near Urrbrae House.

The State Commission Assessment Panel approved the plan in August 2021 with the support of Heritage SA and the City of Mitcham. Glassenbury’s construction firm was engaged a month later to start preparing for the gatehouse’s “stone by stone” dismantling.

He said upon inspecting the building, the “cracks and the internals were so bad” that it was “probably not habitable for use”.

“The outside looked quite nice, but if you went inside you’d be horrified,” Glassenbury said.

The interior of the Urrbrae gatehouse prior to its demolition. Photo: DIT/supplied

Before any demolition work could begin, the project team had an extensive documentation task. FMG Engineering created a full 3D scan of the building, and the gatehouse was photographed from top to bottom, for the purpose of cross-referencing during the rebuild.

The largest component of the job was stonemasonry, with each stone and brick requiring measurement down to the width of the mortar which held them together.

“There were some stone pieces that had already cracked before we got there, just due to the movement and likely loading on particular stones,” Rander said, highlighting a couple of stones that were “basically split down the middle” on arrival.

“There was a lot of movement in the back and the front part of the building – like they’d almost moved independently of each other.”

The project team devised a plan where each stone would be removed, individually marked with vertical and horizontal lines, placed on a pallet with stones from the same wall section, wrapped in plastic, and catalogued in a numbered grid formation.

We needed to make sure that we had everything recorded, because once it’s down there’s no going back to check measurements.

The square-metre pallets were then stored in shipping containers and sent away on trucks.

Dismantled stones from the gatehouse were sorted on pallets before being shipped off to storage. Photo: DIT/supplied

Glassenbury said the stones needed to be “stored in a manner that it could be put back up in exactly the same configuration”.

“They’re all different shapes and sizes and if we just randomly put it back up, Murphy’s Law would be that we’d get to the end and run out of stone,” he said.

“So we did a lot of detailed measuring on the stone – even to the extent of the width of the mortar between the stone so that the spacing is right.

“If we lay the mortar back a bit thinner [when we rebuild the gatehouse], by the time we get to the end we’re going to be short.”

Plans also had to be drawn up to salvage the original and irreplaceable Aldgate sandstone which formed the gatehouse’s lintels, the horizontal beams that span the top of the windows.

“Basically, the stone was removed down to those levels and then we had a crane come on site and they were carefully lifted off and transported out to a pallet because we were fearful that they would snap or break because they were quite brittle,” Glassenbury said.

The Aldgate sandstone, which is no longer available as it was sourced from the now-decommissioned Aldgate quarry, also had to be salvaged from parts of the gatehouse’s walls and corners.

The entrance to the gatehouse halfway through the demolition process. Photo: DIT/supplied

“So, we’ve basically pulled the brickwork down obviously from the top down, so the first thing we started was with the chimneys, came down to roofline, then the roof came off and the roof framing could go and then we could pull the brickwork down,” he said.

“And then as we got down to the lintels then they came off.”

The removal of the lintels, observed by Heritage SA, then exposed the old glass windows – all of which were taken off and stored in custom plywood boxes.

A view of the original, hand-drawn glass windows from inside the gatehouse. Hand-drawn glass was a common glass manufacturing method in the Edwardian era before the introduction of machines. Photo: DIT/supplied

“It was almost a reverse building process where normally you’re building from the ground up where we were building – well, ‘unbuilding’ – from the top down,” he said.

“Pulling it down and cataloguing it all was the time-consuming part because we needed to make sure that we had everything recorded, because once it’s down there’s no going back to check measurements.”

In all, the process to dismantle the gatehouse took three months, ending in May 2022.

‘There was definitely risk’: Preserving the gatehouse piece by piece

Glassenbury reports that, so far, none of the original glass windows or Aldgate sandstone has been damaged during the project.

“They’ve been carefully stored so – touch wood – no glass gets broken or anything and we can get them back in without breaking the glass. That would be amazing,” he said.

Video: Department for Infrastructure and Transport

Back in December 2020, then Marshall Government Transport Minister Corey Wingard pointed to the risk of moving the gatehouse as one of the reasons to demolish the building rather than relocate it.

Glassenbury says “there was definitely risk involved in the project”.

“It was our job to work with the Department and obviously mitigate this risk as much as we could and work very carefully, but with anything we do there’s always an element of risk.”

Rander said one of the concerns was that the stone would begin to crack once the demolition team made their way down the building structure.

“The stone was in reasonably good condition when we went through the process,” Rander said.

“One thing we were worried about was obviously the further we get down we were concerned that some of the stone would be brittle and break apart.”

The dismantling also required the removal of an asbestos-shingle roof and an internal roof frame which “wasn’t to the standard of today’s timber framing code standards”, according to Glassenbury.

“There’s been a lot of care obviously trying to preserve all elements of the building that we can reuse,” Glassenbury said.

“We don’t really want to put anything new in where we don’t have to, [but] there are some things we just have to.”

Video: Department for Infrastructure and Transport

Building a gatehouse for the next 130 years

“To be honest, putting it back up will probably – hopefully – be the easy part,” Glassenbury said.

Early works began in December to rebuild the gatehouse on a new concrete footing in the southeastern corner of the Waite Arboretum, near Claremont Avenue.

A render of the rebuilt Urrbrae gatehouse. Image: Dash Architects

The new gatehouse will reuse the floorboards, fireplace, skirtings, architraves, window frames and seals of the original building. It will also have the same interior layout.

Other elements, such as the ceiling, roof, and internal wall plastering, will be replaced, while the salvaged stones and bricks will be repointed with a new mixture of lime and sand resembling the gatehouse’s original form.

You want to make them distinctly different so that’s it’s clear that the original was this bit, and the new building is that bit, and that we’re not trying to fake something that’s not original.

The size of the building will also increase by 116 square metres, allowing it to accommodate up to 40 people when including its modern extension.

“Effectively, we’ll be trying to build it in two parts,” Glassenbury said.

“So obviously there’s the rebuild of the original part which will be a bit slow and painstaking,

“But then the rear part is more modern so that can go up – but obviously there’s elements that crossover and they’ve got to work together.”

Rander said the contrasting styles between the modern steel extension at the rear and the old gatehouse was “exactly the brief from… Heritage SA”.

“The roof design itself is obviously trying not to, I suppose, take away from the heritage structure, so it’s not trying to out-stage the heritage structure,” he said.

“The intent of this is… it’s going to be stone by stone, so there’s really not going to be a lot of difference to what the average person will see of what was there as to what’s there now.”

Glassenbury said trying to build a rear extension that emulated the original gatehouse would have been “completely the opposite of what’s intended for heritage principles”.

“We want to restore the original building back to its original state, but we don’t want to build a new extension and try and make it look old,” he said.

“You want to make them distinctly different so that it’s clear that the original was this bit, and the new building is that bit, and that we’re not trying to fake something that’s not original.

“It’s still sympathetic to the original building and in keeping, but it’s clearly new.”

The grounds of the Waite Arboretum, where the new-look gatehouse will soon be rebirthed. Photo: Thomas Kelsall/InDaily

The new gatehouse, designed by Adelaide’s DASH Architects, is scheduled to be completed in late 2023.

Glassenbury said the rebuild would be more time-intensive than a standard construction project.

“It’s not the case of ‘oh we’re just laying a stone wall’,” he said.

“This will probably take two to three times longer than laying a stone wall because every stone needs to be carefully set in the grid formation that we’ve done.

“You can’t just grab something off the pallet and put it up, so that’s where the time is lost a bit in cross-referencing our records and checking that we’ve got it right.”

Meanwhile, the redesigned Cross Road and Fullarton Road intersection opened to traffic on December 13 with the gatehouse – for 100 years the prominent entry point to Peter Waite’s Urrbrae estate – no longer present.

The former site of the Urrbrae gatehouse on January 19. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Google Maps imagery showing the Cross Road and Fullarton Road intersection before and after the gatehouse’s removal.

Rander said with proper maintenance and care, the new-look gatehouse can live on for another 100 years in its quieter surroundings.

“With these structures, you do have to have a bit of a maintenance regime, so you can’t set and forget,” he said.

“But if it’s taken care of and kept in reasonable condition – that’s the intent that it will go for another 100 (years).”