Named, shamed, interrogated while dying: The women the law put last

SPECIAL REPORT | With abortion rights under siege in the United States, Simon Royal looks at the reality of life for many South Australian women, and their doctors, in our not-so-distant past.

This article contains material that will be distressing for some readers.

Too often for her liking, listening to the news these days reminds 92-year-old Dr Aileen Connon of the world when she started out in medicine.

“I’m very sad about what’s happened now in the United States, following the Supreme Court decision”, Connon said. “In its most extreme, to not be able to get an abortion in cases where you have been raped, or in cases of incest, it is quite bizarre… then this morning, I heard on the radio that women fleeing from Ukraine to Poland, the ones who have been raped, they are having difficulty getting an abortion because Poland is very strict with its legislation.”

Sitting in her living room overlooking the Patawalonga, far removed from European conflicts and American culture wars, the doctor shakes her head and offers a blunt diagnosis of the ailment: “It’s a matter of men setting the rules, and they don’t seem to have too much compassion.”

Laws that lacked compassion or nuance helped produce the patients that shaped some of Aileen Connon’s first professional experiences.

She did her initial training at The Queen’s University of Belfast, though is quick to add, with just a hint of residual brogue: “You do know I’m a Scot”! There were only three women obstetricians in South Australia in 1963, when Connon started with the University of Adelaide’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

In the years between graduating in Northern Ireland, and joining academia in Adelaide, Aileen Connon worked in The Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital in Melbourne. It was there she was invited to become an obstetrician and gynaecologist. Throughout the late ’50s and early ’60s, as part of her training, she worked in the abortion wards, treating women who’d had ‘backyard abortions’.

At that point, legal abortion, effectively, didn’t exist in Australia. Sometimes women, in Melbourne or Sydney at least, would find a doctor willing to take the risk. Sometimes they’d find a former nurse or midwife who knew about proper hygiene.

I think the wards where we treated women with infections after abortions were some of the saddest places I’ve worked in

Connon’s experience is that women who weren’t so fortunate to get that help, or who tried to give themselves an abortion, almost invariably ended up in hospital.

“They would arrive in casualty, as the accident and emergency department was called in those days,” she said. “Often they’d be bleeding profusely. I remember we were trained how to quickly get the clot out of the cervix, which was keeping it open, to stop the bleeding, and then somebody else would put a drip in and they’d run in some fluid and work out what sort of blood they needed, and so on. So that was the standard thing, but the ones who came in with that plus an infection, they were seriously, seriously ill. Unfortunately, occasionally, those women would die.”

One type of infection was a particularly formidable foe: gas gangrene. The hospital pharmacy would send ampules of antiserum for those patients, and through the night, every hour, Aileen Connon, or another young doctor, would administer it.

“If you think of the First World War when the troops in France were in the trenches, there was no penicillin, nothing whatever, and not too much knowledge about infections, either,” she said. “You often used to hear of men having their legs amputated because they had gas gangrene. Now the organism that produced the gangrene is called Clostridium welchii, and it’s the same organism that caused the serious infections in the women who were having abortions.”

Men in battle, women in backyards. That both should suffer the same terrible illness isn’t an irony, it’s an indictment. For those who survived, Aileen Connon says their lives and their health were never the same.

“They’d have blocked fallopian tubes and they’d have been infertile. Some of them would have had chronic pelvic pain, possibly for the rest of their lives. I would suspect that their life span would have been interfered with, but I have no data on that.”

Aileen Connon: “It’s a matter of men setting the rules, and they don’t seem to have too much compassion.”

The dying deposition of Dawn Dean

The police, too, paid regular visits to the wards, collecting evidence to prosecute abortionists. The statements the women gave are called dying depositions. Aileen Connon’s memory of Melbourne is the officer would wait outside the ward until a doctor told him he could come in. Connon isn’t sure of what happened in Adelaide’s hospitals, but the state archives soon reveal very much the same practice here.

Detective Bernard Harvey had finished speaking with Miss Dawn Dean when, according to Harvey, she asked him to sit by her bedside for a time.

“I went to go,” Harvey said in his statement to the coroner, “[but] she said, ‘stay and talk to me a while longer. I get afraid when I am on my own’.” The pair talked for another hour or so: a “general conversation about the Northern Territory”.

Before moving to Adelaide, Dawn Dean had been working in Alice Springs. Despite finding a common interest, this meeting between the young woman and the seasoned policeman was far from a social encounter.

Dawn Dean was in the DaCosta ward at the old Royal Adelaide Hospital. The 26-year-old stenographer was gravely ill after a ‘backyard abortion’. All of ‘those’ patients were put in DaCosta.

It was July 23, 1947. Bernard Harvey had gone to the hospital on business. The detective wanted to persuade the young woman to reveal the name of the abortionist.

At first Dawn Dean refused, saying, “she’d made me promise I wouldn’t tell on her”, so Harvey instead asked her to tell how she’d come to be in her “situation.” The young woman was in Adelaide to marry “her boy” – a 39-year-old man named Martin Cain.

“He kept putting it off – I got into trouble – he wouldn’t marry me,” Dean recounted.

She told Harvey she “hoped her mother would not be too late” to see her. The detective noted Dean then began to cry. She begged that she not be made to see the woman who performed the abortion – “I would be too ashamed to face her.”

When detective Harvey replied there’d be no need to see the woman until she was better, Dean answered: “I’m not going to get better. I’m going to die tonight.”

The detective then pressed his cause, and asked once more: “Will you tell me the name of this woman and where she lives?” It was at that moment Dawn Dean changed her mind.

“’I suppose so,’ she said, ‘I don’t want anyone else go through what I have…[it is] Mrs Bryant, 30 Rowells Avenue or Rowells Crescent I think it is, Kilkenny’.”

The young woman described the method and equipment Mrs Bryant used. She said it was done at her home, not Bryant’s, and that she wasn’t sure how much the ‘procedure’ cost. Dean told the policeman to ask Martin Cain about the money. “He was paying for it..he gave me her [Bryant’s] name and address.”

“I feel much better now that I have told you and got it off my conscience and if I can see my Mum now I will go happy, this world is a very unhappy one and I think I might find something better,” Dawn Dean concluded.

Detective Harvey had his dying deposition. He didn’t waste time. At 10 o’clock that same night, Bernard Harvey knocked on Mrs Bryant’s door. Her first name was Edith.

Named and shamed

Edith Bryant was 53, married, with at least one child – a son in his early 30s – and performed “home duties”, to use the phrase of the day. Edith Bryant’s journey through the justice system had just begun, while Dawn Dean’s would end a week later.

On August 1, 1947, Dean died of renal failure, though the pathology report additionally cites “a profound septic condition”, plus necrosis in the “mouth, lungs and uterus”. This catalogue of pain and suffering was caused by the ‘old mate’ from the trenches: Clostridium welchii.

We don’t know if Dawn Dean got to see her mother one last time.

Edith Bryant’s name and address were in the newspaper the day after detective Harvey’s visit. The story was headlined, “Serious Charge Against Woman”. Dawn Dean’s details were made public after her death: her name, age, profession, and, obviously, the fact she was unmarried, pregnant, and had sought an abortion. But there was more. Even Dean’s address – 28 Cawthorn Street, Southwark – was printed. Southwark was the old name for part of Thebarton.

Martin Cain, Dawn Dean’s “boy”, came in for less attention. Although he procured Edith Bryant’s services, Cain apparently wasn’t charged with any offence.

There was no mention in the newspapers that Cain and Edith Bryant previously knew one another, having met at a party seven or eight years earlier. It wasn’t even spelt out that Cain was a vital ingredient in Miss Dean’s pregnancy – the father. Suspicious readers were left to jump (correctly) to that conclusion for themselves. There’s a lot in there to astonish, if not affront, modern expectations.

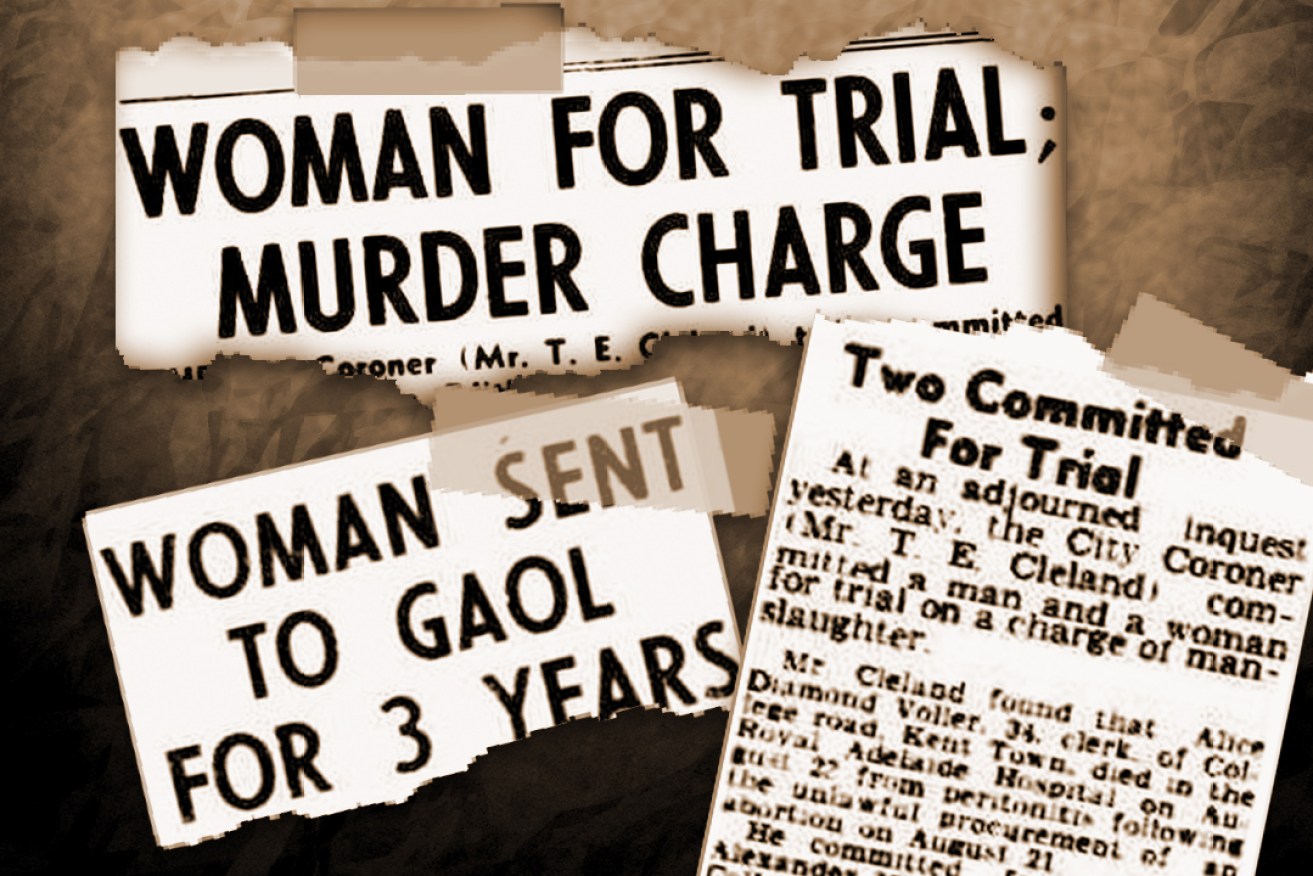

But the most remarkable thing about the case of Dawn Dean and Edith Bryant is, at the time, it was wholly unremarkable. Every year, there’d be charges of murder stemming from a ‘backyard abortion’ death.

Usually, it was a female abortionist appearing before the courts, but not always. In 1948, a husband and wife were sent to trial. In 1950, another man and woman. The same again in 1951, and so on, right up until the ’70s.

On September 10, 1969, as parliament was debating abortion law changes, The Advertiser reported two men – “labourers’’- had been charged with murder. One of them, the husband of the dead woman, reportedly told the court his wife had “pestered him for an abortion”.

Working class areas such as Ethelton, Port Adelaide, and Kilkenny appear regularly as the addresses of both the accused abortionist and the woman who had the abortion. None of this surprises Dr Barbara Baird, Associate Professor of Women’s and Gender studies at Flinders University. In 1990, Baird did an oral history of South Australian women who’d had abortions before the law was reformed.

“The one thing that stood out for me most was the very clear cut class division in the nature of the experience women had,” Baird said. “It was really clear that women who came from working-class backgrounds were most unlikely to think about approaching a doctor… they go to ‘backyarders’ as they were known, although I don’t like the connotations of that term.

“The women I interviewed who came from middle-class backgrounds, all of them travelled to either Sydney or Melbourne to seek abortions from doctors… it was about different attitudes to abortion, different attitudes toward doctors, different attitudes to their bodies, I think, and a bit about money, although not entirely.”

Abortion sits at a contentious crossroad: when do we, or when does the state, rather, assert that life begins and a women’s bodily autonomy ends?

In 1969, the South Australian parliament first codified and underpinned the circumstances in which a woman could legally obtain an abortion. That legislation sat untouched for more than 40 years, until the South Australian Law Reform Institute was asked to review it, and recommended changes. The results of that review came into effect earlier this year.

SALRI director, Professor John Williams, says the shorthand summary of what changed is to look at who is now at the heart of the law.

“The centrality of the woman, as against the rights of the doctor, is what has been changed,” Williams said. “I would say that it’s the woman who is at the centre of the process now.

“The question is, ‘who is best to decide’? Ultimately, when you have these large questions, like abortion, it comes down to who is best to decide. What we’ve tried to do in South Australia is leave the moral question to the woman. I would argue the burden of that question, in some ways, should sit squarely with those who are most affected by it.”

The Americans made abortion a legal question, and so it’s been decided by lifetime political appointees to their highest court.

South Australians viewed abortion as a policy question, to be decided by the 69 democratically elected members of parliament. A specialist in Australian constitutional law, as well as a longtime admirer of past US Supreme Courts, John Williams sighs when asked what he thinks the fall of Roe versus Wade means.

“Clearly this will not stop abortions in the United States. They will happen,” he said. “What the decision may have done is put 80 million people outside of the law. That doesn’t mean they won’t seek abortion services, they’ll just do so in the shadow of the law, and when they are in that unregulated area there will be the unscrupulous people who will profit out of that, and people will die because of it.”

John Williams and Barbara Baird think public support for access to abortion is strong in this country. Indeed, Baird argues outrage over the American experience has strengthened that support. Because of that, both firmly believe there’ll be no change of policy here. But when it comes to the dark art of political tactics, and the paths to power they may offer, Williams isn’t so certain.

“The Americanisation of Australian politics is [happening] in so many ways,” Williams said. “Just with campaigning strategies – Americans are the past masters of that very finessed movement to target particular groups of people, to get them motivated. I’m sure that there are some politicians here, especially independents, or those who are trying to change the focus and direction of their own parties, who will see this as a good litmus test.”

History’s strange turns

It took a long time for South Australia to get where it is now – an imperfect present, for sure, but still surely better than the unyielding past.

At least the courts were quick back then. Twelve weeks after her arrest, Edith Bryant was sentenced to three years’ jail for the unlawful killing of Dawn Dean. Justice Abbott found she’d committed the offence “without decent cleanliness”. He also noted the sentence could have been life. His honour ignored police evidence that “Mrs Bryant was a known abortionist.”

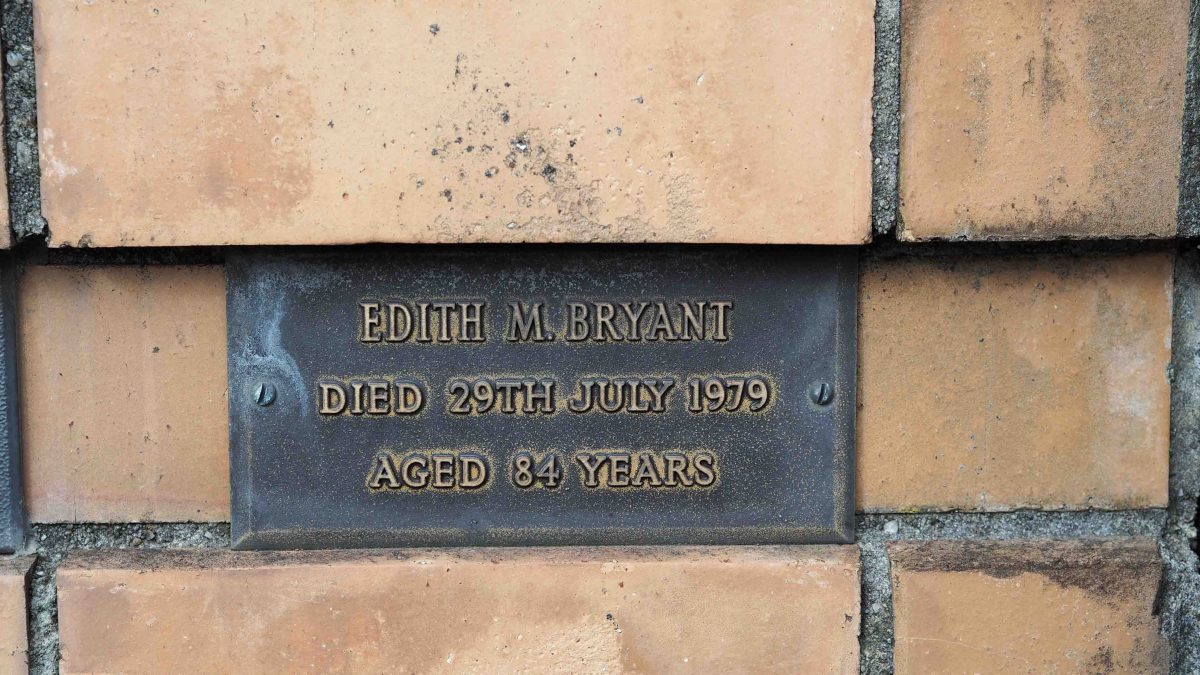

Edith’s husband, Harold, died in the 1950s. When Edith herself died in July 1979, aged 84, Harold was described in the death notices as her “beloved husband”. Other family members are mentioned, too. It means that although Edith Bryant seems to have lived a quiet life after serving her sentence, she did not die alone and unnoticed.

Nevertheless, the universe does relish the odd pointed co-incidence: 32 years to the day after Dawn Dean’s death, Bryant’s ashes were interred behind a simple plaque at St George’s Anglican Church in Magill.

Edith Bryant’s simple memorial plaque at St George’s church in Magill.

In 2005, recognising a long career dedicated to the advancement of women’s health and well-being, Dr Aileen Connon was made a Member of the Order of Australia. She’s never forgotten what things were like when she was young.

“I think the wards where we treated women with infections after abortions were some of the saddest places I’ve worked in,” she said. “Being there was an eye-opener to me.”