SA’s “hidden plague” of incarcerated children

South Australian primary school-aged children – some as young as 10-years-old – were incarcerated 133 times over the past year.

Kurlana Tapa youth detention centre at Cavan. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Most 10 to 13-year-old children detained during the 2019-20 financial year had disabilities, were Aboriginal and/or were cared for under the guardianship of the Child Protection Department.

A report tabled in parliament yesterday by independent watchdog, Training Centre Visitor Penny Wright, shines a light on the number of young children in South Australia whose behaviour is deemed so dangerous that they are forcibly detained at the Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre at Cavan.

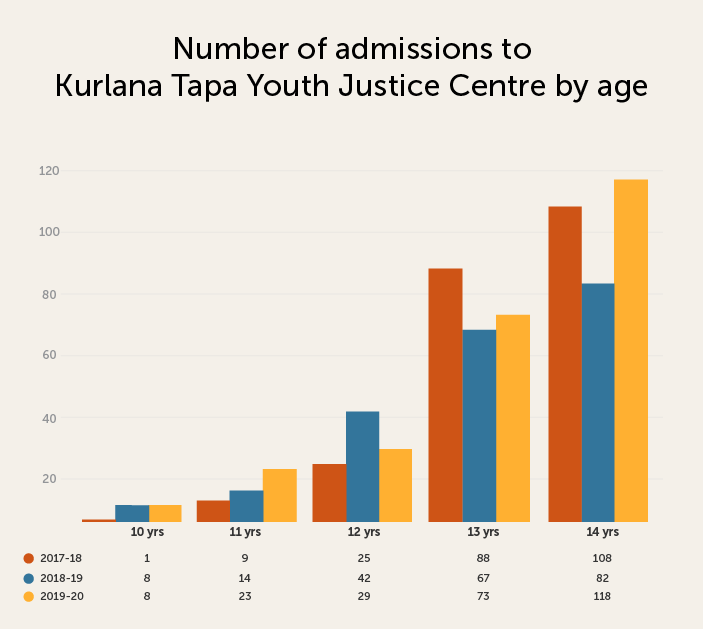

Last financial year, 21 per cent of Kurlana Tapa’s detainees were aged between 10 and 14.

But children aged 10 to 14 were overrepresented when it came to the number of admissions, with each returning to the centre almost four times on average in the same year.

“We are talking about this year having 35 individual 10 to 13-year-olds detained at the centre – essentially a classroom of children and young people – but those 35 individuals were detained 133 times, so it meant that they constituted 20 per cent or one in five of all admissions to the centre,” Wright told InDaily.

Wright’s report states a “highly concerning” number of younger children caught up in the youth justice system find themselves repeatedly entering into and out of detention before they reach high school.

When I was 10, I was locked up. I’ve spent three birthdays over there

It states the under-14 “frequent flyers” struggle to comprehend the nature and implications of their alleged offending, and find the bail process and associated bail conditions confusing, prompting repeat breaches.

“This suggests that detention is not a particularly effective tool for promoting rehabilitation or deterrence in younger children,” Wright wrote.

“In addition, being detained contributes to, or exacerbates, distress and disruption in their lives, with flow-on effects for their education and the ability to form trusting relationships in their homes and communities.

“We are not aware of any program operating in South Australia that directly addresses these concerns and supports these children to address underlying reasons that lead to their incarceration.”

Data: SA Training Centre Visitor Annual Report 2019-20. Graph: Mel Ramsey/InDaily

A separate report released by Wright in July quotes detainees who said they were bullied at Kurlana Tapa from a young age.

“When I was 10, I was locked up. I’ve spent three birthdays over there [Jonal campus] and two in here [Goldsborough]. The first time, I was 10. It was very scary,” one is quoted.

Another said: “When I first came in at 12 years of old, I was in the games room: they [other detainees] would threaten me … I was scared of them and I was too scared to tell staff: one was 17 years old.”

Wright told InDaily for some of these young people “custody just becomes the default”.

She said they were “not hardened and violent criminals, but scared kids often being held on remand because they have nowhere else to go”.

“Clearly responding to their behaviours by locking them up is not changing their behaviours, it doesn’t seem to be an effective deterrent and it’s not having a rehabilitative outcome, so why are we doing it?,” she said.

Wright’s report is one of the only sources of information that shows the extent of youth offending in South Australia.

It is unknown how many times children aged between 10 and 14 are charged with an offence in South Australia, with SA Police telling InDaily that it does not collate the information in one location.

InDaily submitted a freedom of information request to SA Police in July asking for the number and nature of offences committed by 10 to 14-year-old children over the past 10 years.

SA Police said it would not be logistically possible to collate 10 year’s-worth of data, but it could provide the information from 2018 to 2020, at a cost of $423.

It comes as momentum builds to lift South Australia’s minimum age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14 years, to prevent young children from getting caught up in the criminal justice system before they reach maturity.

Greens MLC Mark Parnell introduced a Bill into the Upper House in July to lift the age of criminal responsibility to 14.

He described the incarceration of children as “a hidden plague upon this land” that “disproportionately causes harm to the disadvantaged, to racial minorities, the poor and those with disabilities”.

But Attorney-General Vickie Chapman said she would wait until her state and territory counterparts reached a national consensus before moving to change South Australia’s minimum criminal age.

These are highly vulnerable children and we owe it to them to make sure they get back on the path to thrive

A meeting of attorneys-general in July decided that there was still work to do on what would replace the current system should Australia’s criminal age change, meaning children aged as young as 10 will continue to be arrested, charged and detained until at least the middle of next year.

Wright, a former Greens senator, said it was “disappointing” that progress on raising the age of criminal responsibility was “so slow”.

“There’s been really welcome news that the ACT has been moving to make that change and I really wish that the other jurisdictions would heed all the expert evidence from the Australian Medical Association and so many other child development and health experts, who say it’s inappropriate to be locking up children in the way that we do.”

“These are highly vulnerable children and we owe it to them to make sure they get back on the path to thrive.”

Over 28 per cent of children and young people locked-up at Kurlana Tapa last financial year were under a guardianship order.

Just over 48 per cent were Aboriginal, despite Aboriginal children representing less than five per cent of South Australia’s total child population.

According to data published by the SA Council of Social Service in 2015, if the rate of detaining Aboriginal young people was the same as the general child population, South Australia would save over $12 million each year.

Department for Human Services data shows nine out of every 10 children at Kurlana Tapa have a disability or a disability-related need.