Turning the Aboriginal Art and Cultures Centre vision into reality

Adelaide’s Aboriginal Art and Cultures Centre could rival architectural icons such as the Sydney Opera House and use cutting-edge technology to portray First Nations culture in never-before-seen ways, but could also be at risk of bureaucratic stonewalling. Stephanie Richards talks to the man appointed as a key leader of the $150 million gallery.

Aboriginal Art and Cultures Centre Ambassador David Rathman AM. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

Newly-appointed Aboriginal Art and Cultures Centre ambassador David Rathman AM, an Eastern Aranda descendant with family connections to the Kokatha, Arabunna and other South Australian Aboriginal nations, believes a gallery dedicated to Indigenous Australian culture in Adelaide is long overdue.

The SA Museum board member and Aboriginal Advisory Committee chair has for about nine years spearheaded calls to build a new public institution to display the museum’s 30,000 spiritually – and anthropologically-significant cultural artefacts, which are mostly stored in a leaking suburban storage shed, at risk of irreparable damage.

When then-Opposition leader Steven Marshall announced ahead of the 2018 state election that he would build an “Australian National Aboriginal Art and Culture Gallery” as the “jewel in the crown” for the redeveloped old Royal Adelaide Hospital site, Rathman saw a golden opportunity.

“I was always in the Premier’s ear about the heritage collection in the museum and ensuring that we get a strong representation of Aboriginal cultures from around Australia when we’re doing exhibitions or telling the story,” he says.

“The centre is not a pet project of the Premier – this is a project which many of us have been waiting for, hoping for, agitating for and now it’s going to hopefully arrive.”

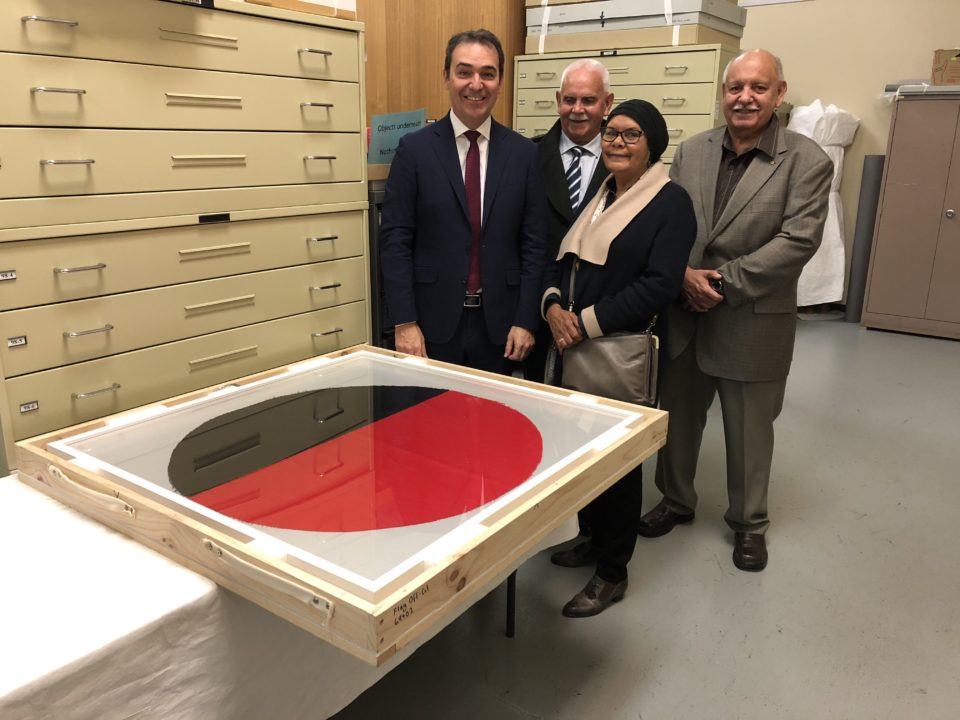

Premier Steven Marshall with David Rathman and members of the SA Museum’s Aboriginal Advisory Committee at the museum’s storage facility in 2018. Photo: SA Museum

To be located next to the Botanic Garden, the yet-to-built AACC is touted as “the gateway to the oldest living cultures in the world”, combining traditional story-telling and modern technology to lure international and interstate tourists to the city.

It will display artefacts sourced from across South Australia’s cultural institutions, including the SA Museum and Art Gallery of SA, to help people to gain an appreciation of Aboriginal peoples’ connection to country.

Less than one week after being appointed ambassador, Rathman meets InDaily at the SA Museum to discuss his vision for the centre.

I worked too long in the bureaucracy and I know the ins and outs of how they want to control things

It’s his job to promote the AACC to the broader community, and to ensure that Aboriginal people are the ones who decide how their 60,000-plus-year-old cultures are represented.

“This is a job around trying to bring some passion and Aboriginal perspective to the task and to ensure that our science and knowledge of country gets properly represented in the purist form as we possibly can, but using the most advanced technologies to get that across,” he says.

“We talk about reconciliation and (former Prime Minister) John Howard once said we need practical reconciliation – well I think we need active reconciliation, not practical.

“We need something that’s active: you can touch it, I can touch it, we can work together on it.

“That’s really my role.”

In the early stages of his term, Rathman is asserting his ability to speak openly about his vision without bureuacratic interference. Renewal SA – the government agency tasked with developing the Lot Fourteen site – insisted on the morning of InDaily’s interview that a media adviser also attend the meeting.

“I don’t want to be constrained by bureaucracy – I worked too long in the bureaucracy and I know the ins and outs of how they want to control things,” Rathman says.

“Getting that rolling support will be important (as well as) making sure that media outlets like your own are given full, frank and honest information – not trying to create spin as we go through this process.”

Taking ownership of the story

Following the 2018 state election, the new Marshall Government quickly set about scrapping well-advanced plans for a contemporary art gallery at Lot Fourteen to make way for an Indigenous arts and cultures institution.

The move has drawn ire from notable critics, including arts administrator Michael Lynch, who spearheaded the Adelaide Contemporary plans and branded Marshall’s revised vision “a strange hybrid that nobody seems to want”.

But according to Rathman, plans to build an Aboriginal cultures centre in Adelaide were progressing well before the election, with the intention that First Nations people would have full ownership and control over the institution.

Spears currently in storage at the SA Museum. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

“When you hear people say it’s just come out of the blue it hasn’t – it’s been talked about forever,” he says.

“We (the SA Museum Aboriginal Advisory Committee) did a paper with the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation about it being an Aboriginal centre in terms of ownership and then leasing it back to the state.

“Aboriginal people have never controlled their destiny, the money and therefore the action is rather tokenistic, what we have control over.

“Once the Premier announced that he was committed to it, we wanted to see how that panned out.”

Rathman says he is “not tied down” to Aboriginal people having full ownership of the AACC.

Australia’s always portrayed Aboriginal people as a curiosity at best and fairly negatively at worst

Instead, he believes there is an opportunity to partner with the State Government “in a way which will give it a strong Aboriginal sense of management (and) control”.

“We’ve got to keep the Government in the space because there’ll be challenges around how it’s going to operate and function, and if the Government’s in the space we can be sure that they’ll make commitment budgetary-wise both federal and state and we can keep it working,” he says.

“There are opportunities through the business side of it, so it would be good to see some business aspects managed by Aboriginal companies as lease-back corporate arrangements with the State Government.

“There are ways without the physical building and land being under Aboriginal ownership.”

“Something that’s way beyond the design of the Sydney Opera House”

Rathman has high-hopes for the built form and impact of the centre.

He sees it as a place where overseas tourists can get a “gold-plated experience” of Aboriginal cultures and where Australians – both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal – can gain a better appreciation of the country on which they live.

Asked what he wants the building to look like, Rathman responds “it can’t be a box sitting on North Terrace”, but instead “something spectacular” that will “strike Adelaideans, South Australians, Australians and overseas visitors as something they want to go into and have a look”.

A concept image of the “National Aboriginal Art and Culture Gallery”, released by the SA Liberal Party ahead of the 2018 state election.

“We want something that’s way beyond the design of say the Sydney Opera House or the Festival Centre,” he says.

“It’s got to fit, for me, as an expression of the power of the story of country – the spirit of the country, the fact that we are just passing through on a journey.

“If this building can give us that story it would be great. It would be fantastic.”

Inside, Rathman envisions the centre will go beyond “just a bland set of artefacts sitting around in a room” to instead create an immersive experience featuring constantly-changing holograms, virtual reality and performing arts displays.

“Maybe we can make the boomerangs come flying at you so it really feels as though things are happening, rather than people feeling like if they’ve seen one boomerang they’ve seen them all.

“I would like to think that as you walk into this space you’re going to take part in it, rather than it being a stand-up experience.

“But I don’t want to just see it being an event – I’d like it to actually tell a story with scientific value.”

Rathman says his vision is “highly achievable” within the $150 million state and federal-funded budget he has been given, but notes that spending decisions ultimately lie with the Government.

“It’s a matter of coming up with a design, putting that back to Government to see what they think they’re willing to spend money on,” he says.

A place of pride

While the centre is largely marketed as a global tourist attraction, Rathman sees it having a significant impact on South Australian Aboriginal communities.

For centuries Aboriginal people’s culture has been portrayed – accurately or otherwise – in mostly-European museums, outside their control and often without their consent.

I think we’re a fairly patient people, but I’m glad we’re going to accelerate this process

If all goes to plan, the AACC could provide Aboriginal people with an opportunity to take back control of their stories.

“Australia’s always portrayed Aboriginal people as a curiosity at best and fairly negatively at worst and we have to change that hang-up that Australia’s got,” Rathman says.

“We want to create an image of Aboriginal people which most South Australians have never heard or seen.

“There will be a pride of instead of being on the receiving end, we can be on the giving end of the equation in terms of giving back a strong sense of country through story, through dance, through whatever medium we can harness.”

Aboriginal cultural artefacts in storage at the SA Museum. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

The ambassador hopes the centre will provide employment and training opportunities for young Aboriginal people, and further the work already underway by institutions such as Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute and the APY Art Centre Collective.

“It gives back bucketloads in terms of building expertise,” he says.

“We’ve got to make sure that institutions like Tandanya have a space here as well, that Tandanya is a contributor and is made to get some hopefully elevated importance as we go down the track.

“It’s important because that institution has been here 40 years now and it’s important that they become active, remain strong and possibly get spin-off from this particular development.”

2023 opening a “big ask”

Marshall’s announcement in February that the AACC would be open by 2023 raised some eyebrows.

At the time and still today, the centre remains a concept – funded but not yet fully planned, with questions remaining about what it will look like, who will operate it and what it will display.

Asked if he thinks the 2023 deadline is achievable, Rathman diplomatically responds: “If I was a visionary of that type I’d probably say yes.”

“It’s a big ask isn’t it? But I do think that you’ve got to set some timeline, otherwise we could be sitting here talking about this in 50 years’ time.

“I think we’re a fairly patient people, but I’m glad we’re going to accelerate this process.”

A render of the Lot Fourteen development, showing the location of the AACC to the right. Image: Renewal SA

Meanwhile, work continues behind closed doors on the centre.

The Government completed a $86,000 business case in August, but it won’t be released publicly until early next year.

It is unclear what has prompted the delay, but Rathman eludes to ongoing difficulties consulting stakeholders.

“When you’ve got all those institutional inputs and Aboriginal community inputs, it doesn’t all sort of line up,” he says.

“In this case, people got to look at the various reference points from their own organisation in building a business case and I know that some people said, ‘well my support is contingent upon understanding the business case’.

“That’s a fair call, but I’m always interested when non-Aboriginal business, arts, politicians say these things.

“I’ve seen projects in this state start with the flimsiest business cases ever, but because it’s someone’s pet interest and it’s of great value to somebody, it goes ahead and yet we have this sort of, in some cases, stonewalling going on.”

For Rathman, the project is not a question of trust, but faith.

“The resource to start building it is there and we ought to start moving on it.”