Netted, drugged, locked away: the damning face of child mental health in SA

South Australian children experiencing mental crises are being tied down under nets, locked up in seclusion at extreme rates and forcibly injected with sedating drugs, prompting warnings youngsters are suffering lasting harm from coercive health-system practices.

Image supplied.

An InDaily investigation into the treatment of an estimated 20 children a week “sectioned” by police or paramedics under the Mental Health Act and brought to the Women’s and Children’s Hospital have prompted calls for changes and an inquiry from clinicians, experts and senior State Government office-holders.

Nets are being used to tie children to ambulance stretchers to take them to the hospital and, once there, children are being locked in seclusion at a rate which is the country’s highest, far outstripping the national average.

“We collectively don’t take an appropriately therapeutic attitude to these kids when they’re distressed,” said senior child psychiatrist and Adelaide University Paediatric Mental Health Training Unit head Jon Jureidini.

“Of course you’ve got to make [children] safe, but too often a level of force is being used in doing so that’s damaging,”

Professor Jureidini, who trains Women’s and Children’s Hospital emergency department clinicians, said a “significant proportion” of kids’ crises “currently managed with netting, involuntary sedation and seclusion” could be managed less restrictively, given “appropriate training, support and staffing levels”.

“For somewhere between a third and a half of people who have an experience like this the trauma of it has a significant psychological impact on them.”

State mental health laws and policies allow the use of restraint, involuntary sedation and seclusion – where a patient is locked in a cell by themselves – to prevent risks to safety such as violence or self-injury or to administer immediately required medication.

At the same time, the government acknowledges the practices themselves can cause significant harms, including deaths, injuries, emotional trauma and re-traumatisation, and has been committed, since a 2005 intergovernmental agreement, to “reducing use of, and where possible eliminating, restraint and seclusion”.

Researchers say reliance on the practices “backfires”, sparking increased patient aggression that in turn causes trauma, avoidance and then “visceral gut reaction” among staff and that threats to safety have been better reduced by measures such as improvements in patient care and engagement and staff training in de-escalation and diversion.

We bring people in traumatised; we re-traumatise them in the context of apparent ‘health care’…

Professor Jureidini said he would “conservatively” estimate that at least 100 times a year children arrive at the Women’s and Children’s in an ambulance, having been “netted” —restrained from neck to feet under a webbing net strapped to the stretcher.

The SA Ambulance Service, which did not answer questions about netting, says it restrained 36 children aged 17 or under in 2018.

But Jureidini said: “I suggest the SAAS reporting system is far from capturing all incidents”.

It is believed the SAAS data is derived from paramedics reporting episodes of restraint they have been involved in.

Principal Community Visitor Maurice Corcoran, a statutory office-holder who inspects mental health facilities and advocates for patients, said the netting of young people was “something … we’ve raised concerns (about).”

“I’m just concerned … about the level of restraints, and kids are being traumatised by that experience, absolutely.”

Flinders University Professor of Nursing (Mental Health) Eimear Muir-Cochrane said while paramedics were “much more aware these days” about mental health patient issues she had “anecdotally” heard that if a person is “seen as a mental health patient they automatically have to go to the hospital in netting, and that’s discriminatory”.

SA Ambulance Service Chief Executive Officer David Place said SAAS staff were “highly trained in managing patients who present in a distressed state, with de-escalation measures a major focus of all our interactions.

“Restraint is only used … in cases of extreme behavioural emergency and as a last resort option, to ensure patient and staff safety.”

Mandatory SA Health policy says the “potentially harmful non-therapeutic interventions” of restraint and seclusion may be used only when alternative strategies have been tried and warns unjustified restraint “is potentially an assault or unlawful imprisonment”.

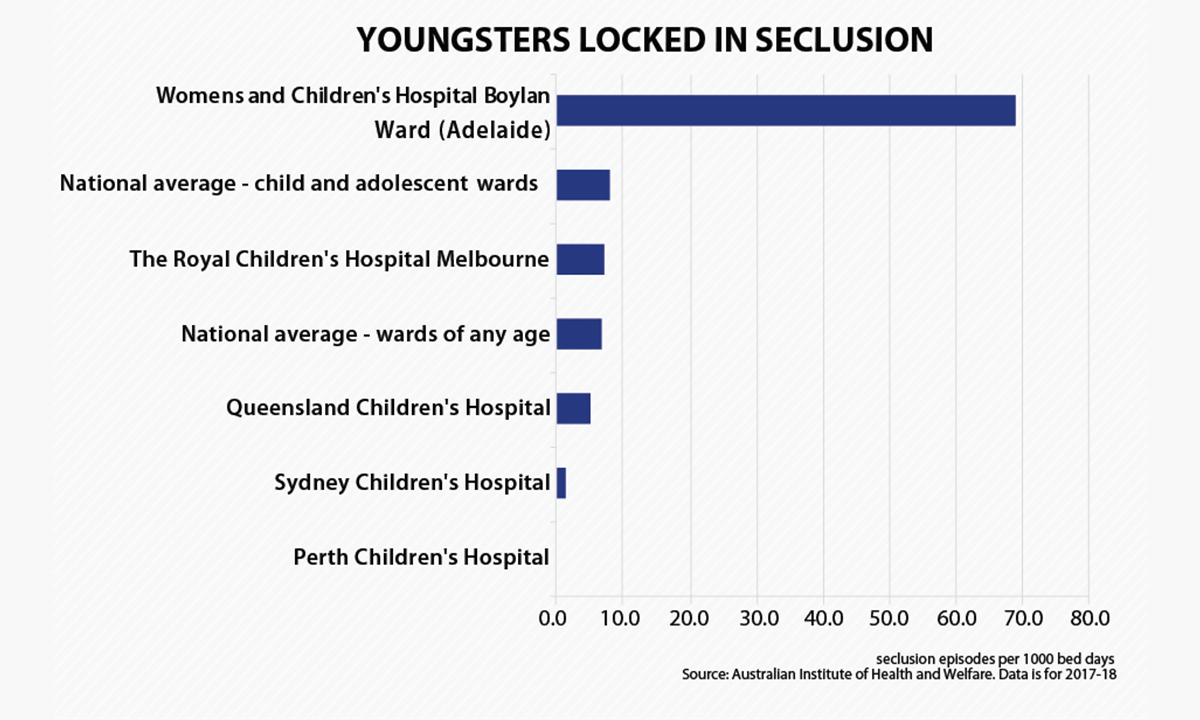

InDaily can reveal the WCH’s mental health ward, known as the Boylan Ward, has been secluding children at by far the highest rate of any mental health ward in Australia for both of the two years for which hospital-specific data is available.

The federal Department of Health’s reporting set on seclusion, mechanical restraint and physical restraint shows the ward’s rate was 851 per cent higher than the child and adolescent national average in 2017-18 and 504 per cent higher in 2016-17.

Women’s and Children’s Health Network Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service Clinical Director Mohammed Usman said seclusion was used “as a last resort” and but acknowledged “infrastructure limitations of the current ward”.

“We acknowledge that the physical environment within Boylan Ward means the best way to safely contain threats of physical aggression or intrusive behaviour towards other unwell patients is to use the seclusion room,” Dr Usman said.

The antiquated ward, the only mental health unit for children in SA, has neither a high-dependency area – used in some other wards to locate higher needs children –nor an outdoors area for patients.

Dr Usman said the hospital was building a new purpose-built child and adolescent mental health ward which would have a “significant impact on safe care practices” and was anticipated to be completed by October next year.

In a statement, SA Health said that Boylan Ward’s average seclusion duration was 15 minutes compared to a national average of 1.3 hours for child and adolescent services; that staff upheld standards “regarding [use of] least restrictive practices”; and that in 2017-18, “two clients accounted for 60 per cent of the total [seclusion] incidents”.

Boylan would still have the highest seclusion rate in the country with 60 per cent of its rate subtracted.

Some children held or treated under mental health laws are involuntarily sedated with powerful drugs, including antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.

An Adelaide mother who asked not to be identified told InDaily that during a 2017 WCH admission her agitated daughter was “forced … into the (Boylan) seclusion room” and injected with a potent antipsychotic, leaving the girl “extremely distraught”, only for staff to announce the next morning she was being released, without providing any discharge information, including a diagnosis.

Principal Community Visitor Corcoran said his office wanted to see “far better understanding and use of staff who’ve got expertise in supporting and engaging with people to deescalate … well before jumping straight into a sedation.”

Community visitors had raised the issue particularly in relation to children with mental illness and one or more other conditions, such as autism or an intellectual disability.

Physical adverse effects of forcible sedation can include respiratory depression, seizure, dehydration, and movement abnormalities, and researchers say the trauma of involuntary injection can put patients off accepting medication or treatment in future.

SA Health did not answer specific questions on sedation but said: “All medication is administered at Women’s and Children’s Hospital in line with designated clinical protocols.”

The Women’s and Children’s Hospital. Photo: wch.sa.gov.au

Professor Jureidini said the commonest reasons for the use of “overly restrictive means of control” was lack of training and support, inadequate staffing levels and redundancy in the staff team, and he stressed he was not blaming front-line health staff.

“You can’t just say, ‘You blokes are doing a bad job’; it’s actually us [public mental health services] who are not providing them with the support and training they need to do a better job,” he said, adding this could be be done with “very little investment”.

Many of the most disadvantaged or traumatised children in the state are massively overrepresented in the paediatric involuntary and emergency mental health system pathways, data cited by the Guardian for Children and Young People suggests.

Guardian Penny Wright she understood that children who live in state care made up about 30 per cent of young people brought in to Boylan Ward by police and ambulance officers in the last year, even though they made up only about 1 per cent of the population.

“It is even more troubling that many of these young people had multiple presentations, up to 24 in one year,” Wright said.

Coercive practices could “be traumatic in themselves and for many kids with a care background reinforce the trauma they have already experienced.”

Commissioner for Children and Young People Helen Connolly slammed the use of ambulance nets as “the spithoods of the health system”, said SA’s Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service was “overstretched” and called for a review of the children’s mental health system.

Melbourne University Professor of Youth Mental Health Pat McGorry said Boylan’s seclusion rates “probably…needs an inquiry of itself” and called for well-resourced, 24-hour mobile home-based mental health care, which he said would reduce presentations at hospitals, allowing their staff “to look after the people that do end up in hospital in a much less desperate or crisis-ridden way”.

Professor Muir-Cochrane said mental health patients should have “completely separate” emergency departments, as the noisy and frightening nature of “mainstreamed” emergency departments reduced the ability of staff to “distract and diverge” patients who could be “out of control”.

Leading SA consumer advocate and 2017 Australian Mental Health Nurse of the Year Matt Ball said: “We bring people in traumatised; we re-traumatise them in the context of apparent ‘health care’; they become less likely to access the system again, unless under duress, at which point we are going to re-traumatise them over and over again.

“Is that about healthcare or is it really about punishment, containment and re-traumatisation?”

For advice, consult a knowledgeable health professional, call the SANE helpline on 1800 187 263 or Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit ReachOut or Beyondblue.

Want to comment?

Send us an email, making it clear which story you’re commenting on and including your full name (required for publication) and phone number (only for verification purposes). Please put “Reader views” in the subject.

We’ll publish the best comments in a regular “Reader Views” post. Your comments can be brief, or we can accept up to 350 words, or thereabouts.

InDaily has changed the way we receive comments. Go here for an explanation.