Boiling point: the behavioural stormfront that follows disaster

SPECIAL REPORT | Climate change is driving a spike in the demand for domestic violence services across Australia, researchers warn, prompting calls for an overhaul of the way communities respond to natural disasters.

A forest left charred after the disastrous 2009 Black Saturday fires. Photo: AAP/Raoul Wegat

It was just after the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria when Monash University researcher Debra Parkinson and her team from Women’s Health Goulburn North East first started to sketch a link between domestic violence and weather-related events in Australia.

The magnitude of the bushfires was unprecedented since Australian settlement, with 173 people killed and more than 2000 houses destroyed.

In the wake of the chaos, domestic violence workers in the Mitchell and Murrindindi shires of central Victoria spoke to Parkinson and her team of what they said was a surge in the number of women seeking help from violence.

“We were in the region and we weren’t really sure how to help because people said they were inundated with volunteers so we thought we’d step back and capture women’s voices,” Parkinson told InDaily.

“We waited about a year on advice from workers on the ground and then we spoke to workers during the reconstruction as well as women in the communities and there was just this significant number who told us about violence in their relationship.”

Of the 30 women interviewed, 17 spoke of increased violence at home or in the community. Nine of those 17 women reported experiencing no violence before the fires and seven spoke of settled and happy relationships prior to the Black Saturday bushfires.

“They had no hesitation in linking the violence really strongly with the impact of the fires on their families and on their partner,” Parkinson said.

“There were two women who really stay in my mind because one was a very senior public servant and one was a doctor (and) both of them had to give up their jobs because the man in the aftermath of the fire was not coping at all.”

The language that they used under their breath when we were presenting the findings was appalling – people and police officers saying ‘this is bullshit’ under their breath.

Parkinson’s research quotes women feeling bewildered by the surge of violence in the community.

“One girl, I ran into her, I think it was between Christmas and New Year, and she had a big black eye… just a girl I knew whose husband works with (mine) sometimes,” one woman is quoted as saying.

Another said: “I think everyone put up with stuff they never normally would have put up with. I know a lot of the call outs to the local police in the first 12 months weren’t reported… Everyone was just looking after each other and they all knew it was the fire impact.”

Parkinson and her team were among the first researchers in Australia to suggest a link between domestic violence and climate events.

There has been overseas work done on the apparent link between natural disasters – climatic and otherwise – and violence. New Zealand police had previously reported a 53 per cent rise in domestic violence after the 2010 Canterbury earthquake, and in the United States, studies showed a 98 per cent increase in physical victimisation of women after Hurricane Katrina.

“In those countries like Australia it was overt, but until we took a look at it after the fires there was nothing – there was no written research in Australia,” Parkinson said.

Towards the end of the Millennium Drought, Monash University senior research fellow Kerri Whittenbury started speaking to health workers around the Victorian town of Mildura, which was suffering from an unrelenting dry climate.

What the workers told her was strikingly similar to the stories of the women impacted by the Black Saturday bushfires.

“They were mentioning that there was an increase in women presenting with issues related to domestic violence and gender-based violence during particular times,” she said.

“Whilst we can’t actually say that the drought caused increases in presentations, it exacerbated the causes that are associated with increases, such as alcohol as a coping mechanism.

“It would spike around bill time – they could have been utility bills or when they needed to pay water.

“It’s all anecdotal though – we don’t have anything concrete.”

Despite the absence of concrete data, Whittenbury said there is a “definite” link between her findings and climate change.

She said while climate change didn’t cause the increased number of domestic violence-related presentations to health services, it exacerbated pre-existing violence and toxic relationships in the community.

“Someone might say, ‘climate change doesn’t cause the drought,’ but we know that climate change is affecting the weather and we’re having more frequent droughts and more frequent floods,” she said.

“The same thing happened with the Queensland floods a few years ago – locals were saying there was more family and gender-based incidences of violence and that was exacerbated by the link to climate change.”

The projected frequency of natural disasters is also a concern for Parkinson.

She said it was crucial researchers and governments start to seriously consider how events such as bushfires, drought and floods impact already vulnerable women in the community.

“Research shows that one in six Australians will experience a disaster and one in three will experience a threat of disaster,” she said.

“With climate change of course we’re expecting more extreme weather events so I think it’s something that really needs to be addressed proactively.”

Flooded homes in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Violence against women increased hugely in the aftermath of the disaster. Photo: AP/David J. Phillip

What’s prompting the spike in violence?

To understand why women are experiencing increased violence following climate events, social work expert Dr Sarah Wendt from Flinders University in Adelaide said there first needed to be an understanding of the root cause of gender-based violence.

“Domestic violence is an expression of the already gendered inequality in society and domestic violence exacerbates that and makes it worse,” she said.

“When you look at climate change or you look at an event such as drought, that doesn’t cause a man to use violence against his partner. That violence will probably already be present (and) what happens is, pressures or stressors might exacerbate that.”

According to Wendt, it is common for people to feel more empathetic towards men than women in the wake of natural disasters.

She said while men are considered responsible for defending their property or fighting fires, women are expected to support and forgive men during stressful moments.

The polarising gender roles, coupled with increased pressures resulting from natural disaster, lead to what Wendt described as a “worsening” of domestic violence in communities.

“All of a sudden domestic violence doesn’t become part of your home – it’s probably sitting there, insidious (and) hidden,” she said.

“The natural disaster just adds to that stress and exacerbates it.”

University of Newcastle professor Margaret Alston said that stress is further exacerbated when families are forced to relocate or temporarily seek shelter from the disasters.

“What climate change and disasters do is destabilise families and livelihoods and put enormous pressure on people who, in the immediate situation, will be more vulnerable.

“Women might lose their support network – neighbours, extended family or others and so the effect can be quite isolating.

“There is also violence that can occur in shelters – after Hurricane Katrina in the US, for example, the number of women were in shelters and who reported incidences of violence was significant.”

Dismissive attitudes

After Parkinson and her team published their research on the Black Saturday bushfires, Women’s Health Goulburn North East began offering training to emergency service workers, community groups and psychologists on responding to domestic violence during and after bushfires.

Trainer Rachael Mackay recounted the first training session held in King Lake in Murrindindi, where workers and some of the research participants involved in Parkinson’s study were in attendance.

“It became really heated when we put up the findings,” she said.

“A lot of men were trying to shut us down in saying that it didn’t happen in certain communities.

“The language that they used under their breath when we were presenting the findings was appalling – people and police officers saying ‘this is bullshit’ under their breath.

“It was like a big cover-up.”

The problem, according to Parkinson, lies in the public’s attitude towards how it responds to women during times of community upheaval.

She said while attitudes were gradually changing, there still remained a perception in some communities that domestic violence perpetrator’s attitudes could be excused during the line of duty.

“When you think about our guys out there on the back of CFA trucks – the volunteer fire brigade – we don’t really think of them going home and being violent to the people they love,” she said.

“To have the notion that this guy who is going out there and fighting fires and might have been one of the town’s local heroes is being violent, is sometimes uncomfortable for a lot of people, particularly in rural Australia.”

“People might say, ‘but Joe’s a really good guy – he is just traumatised and you might need to give him some time’.

“That makes women feel reluctant to speak out about it and when women did say that they wanted to get help they were just not getting it because they were told rough it out with the rest of the community.”

What is happening in South Australia?

While no formal research has been conducted in South Australia linking climate events to domestic violence, social service providers report a link between spikes in domestic violence service demand and hotter weather.

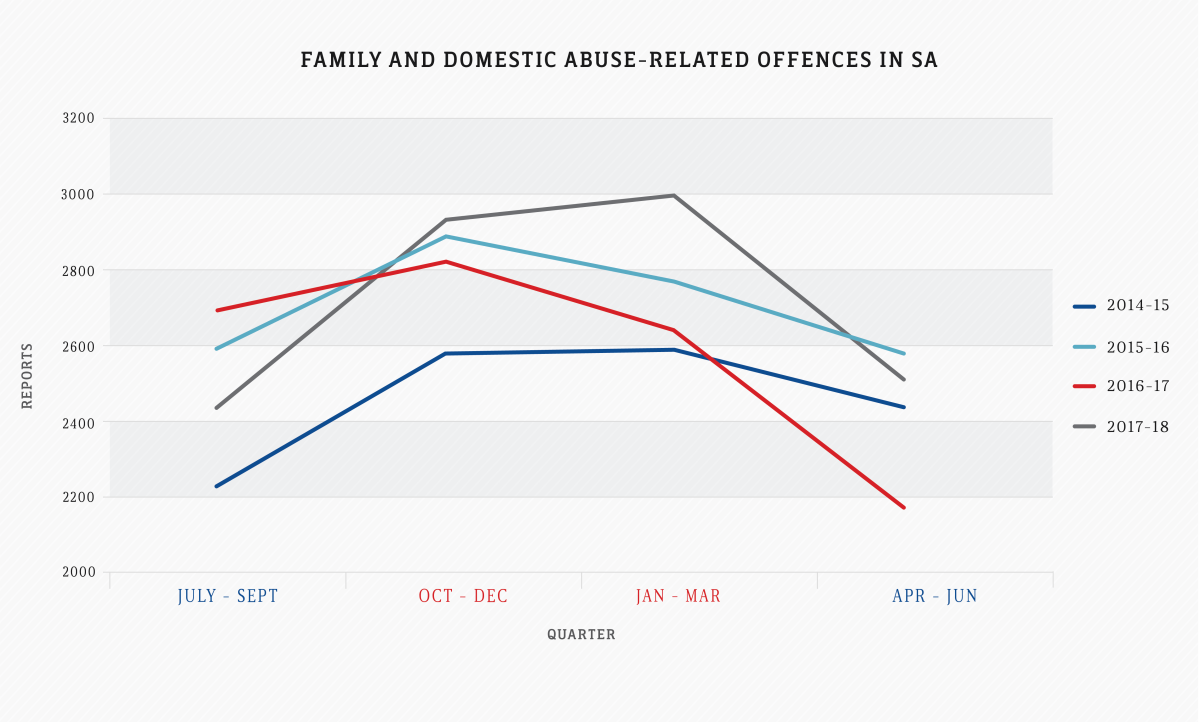

Data from SA Police shows in 2017-18, the number of family and domestic violence-related offenses was almost 20 per cent higher in summer than in winter.

The average difference over a four-year period was 13 per cent.

Data: SA Police. Graph: Nicky Capurso / InDaily

A SAPOL spokesperson told InDaily police statistics had always indicated increases in reports of domestic violence during the summer months.

“This is generally due to a range of factors including increases in daylight hours, social functions and an increase in alcohol and drug consumption,” the spokesperson said.

“We would not be able to link an increase from our statistics of reports of domestic violence solely to climatic conditions.”

But Uniting Communities advocacy manager Mark Henley, whose organisation supports South Australians experiencing abuse in relationships, said “the link between domestic violence and climate change is certainly there from our point of view”.

“The link is really aligned with extreme weather and comfort factors – things like drought or having a number of days over 40 degrees, which anecdotally we’ve found does lead to a spike in service demand,” he said.

“Unrelenting heat and poor housing without adequate cooling facilities or efficient air conditioning is certainly a contributor to domestic violence.

“You have people in houses that are getting hot, there isn’t money to afford air conditioning and that has a definite affect on people’s relationships.”

Anglicare SA CEO Peter Sandeman said while his organisation had not yet analysed its figures to determine a link between the climate and domestic violence service demand, he agreed increased power bills and climate events such as drought had an impact on people’s relationships.

He described the link between climate change and domestic violence as “another frog in the boiling water issue that has been building up without us really appreciating what’s been happening”.

“The difficulty with isolating a particular cause and measuring its effect is that domestic violence is so multi-faceted,” he said.

“There are quite an array of causalities so it is hard to isolate a particular aspect and to correlate increases in domestic violence to that.”

InDaily contacted Women’s Safety Services SA but a spokesperson said the organisation would not be able to comment.

According to the latest State of the Environment Report, published by the Environment Protection Authority in November, the average daily maximum temperature for South Australia is forecast to rise by between 1 and 2.1 degrees by 2050. The EPA predicts this will lead to higher maximum temperatures and even more days above 40 degrees.

Call to change responses to natural disasters

Researchers have called on federal, state and local governments to establish disaster guidelines that prioritise attention to domestic violence.

“Australia seems to be on the alert for natural disasters almost every day now, so if we’re going to address this we need to have a really complex response in how we approach disasters,” Alston says.

“Women’s services are already very aware and in some areas will prepare for disaster threats, but more can be done in ensuring our evacuation shelters are safe for vulnerable women and making sure women are included in the emergency management process.”

Parkinson said it was also necessary to notify communities of the likelihood of increased violence in the wake of disasters – whether that be through public announcements or in disaster prevention literature.

“In the literature given to people after the Black Saturday bushfire, the closest we got was a vague reference to the fact people may feel a bit angry,” she said.

“Ideally what should happen is the police or emergency management authority talks to communities after a disaster has hit to tell them where the nearby domestic violence services are because violence is likely to increase.

“Even in the evacuation centres, just asking women if they have an IVA (intervention order), would make sure that women are safe.”

For Whittenbury, the lack of awareness is in part driven by the lack of quantitative data to suggest a link between climate change and domestic violence.

“We speak with advocacy groups who know what needs to be done – they’ve got anecdotal evidence – but they haven’t got the research funding to address the issues,” she said.

“We’re still stuck at the anecdotal phase without doing some major work where we can actually start to quantify and perhaps set some programs in place that we can evaluate.

“We’ve only just scratched the surface and there’s still so much more work that can be done to help uncover this issue.”

Want to comment?

Send us an email, making it clear which story you’re commenting on and including your full name (required for publication) and phone number (only for verification purposes). Please put “Reader views” in the subject.

We’ll publish the best comments in a regular “Reader Views” post. Your comments can be brief, or we can accept up to 350 words, or thereabouts.

InDaily has changed the way we receive comments. Go here for an explanation.