Children need a voice, say academics

From cyberbullying to safety at home, new research from Flinders University strongly supports the findings of an extensive survey of more than 1,600 children in South Australia which calls for a formal and more “powerful” advocate for their rights.

“What we consistently hear, both in South Australia and in overseas studies, is that children and young people want a Children’s Commissioner or ‘champion’ for their best interests,” says Professor Phillip Slee, from Flinders’ School of Education.

“Children want to be heard by someone who listens and really understands their points of view,” he says, pointing to evidence of widespread concerns about appearance, health and wellbeing, bullying and personal safety.

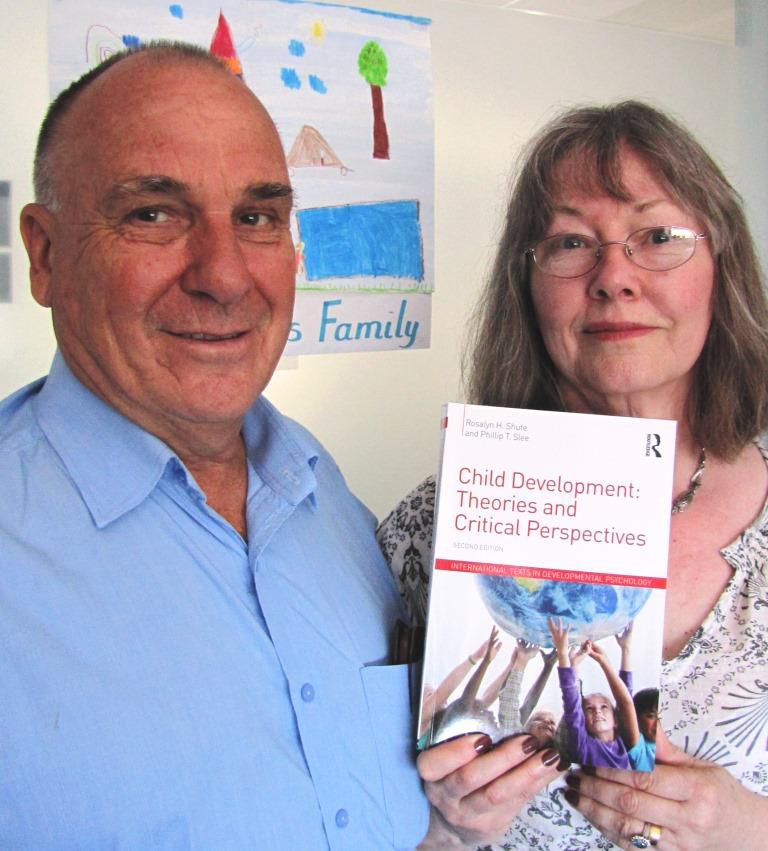

Professor Slee and Flinders University Adjunct Professor Rosalyn Shute have taken the unusual step of including the voices of young people from around the world in their new book, Child Development: Theories and Critical Perspectives (Hove: Routledge).

The book, which dedicates a chapter to considering the testimonies of young people, investigates the psychological development of children.

All of the evidence supports the need to give children and young people a more powerful voice in their development, including a formal route for their opinions on a broad range of topics affecting them to be heard.

“While on the State Government agenda, South Australia is still the only jurisdiction in Australia without a Children’s Commissioner,” says Professor Slee, who runs the Student Wellbeing and Prevention of Violence (SWAPv) Research Centre at the School of Education.

“Almost 10 years ago, the Council for the Care of Children was established to advocate systematically and advise government on a range of matters that our young people need to grow up safe, happy, healthy and socially included in South Australia,” says Professor Slee, who is a member of the Council for the Care of Children.

Professor Slee and Professor Shute with their new book for teachers and other professionals.

“Children want to be heard by someone who is a formal and powerful advocate for their rights,” he says, pointing out that thousands of Australian school children suffer face-to-face bullying every day and thousands more are bullied or vilified online.

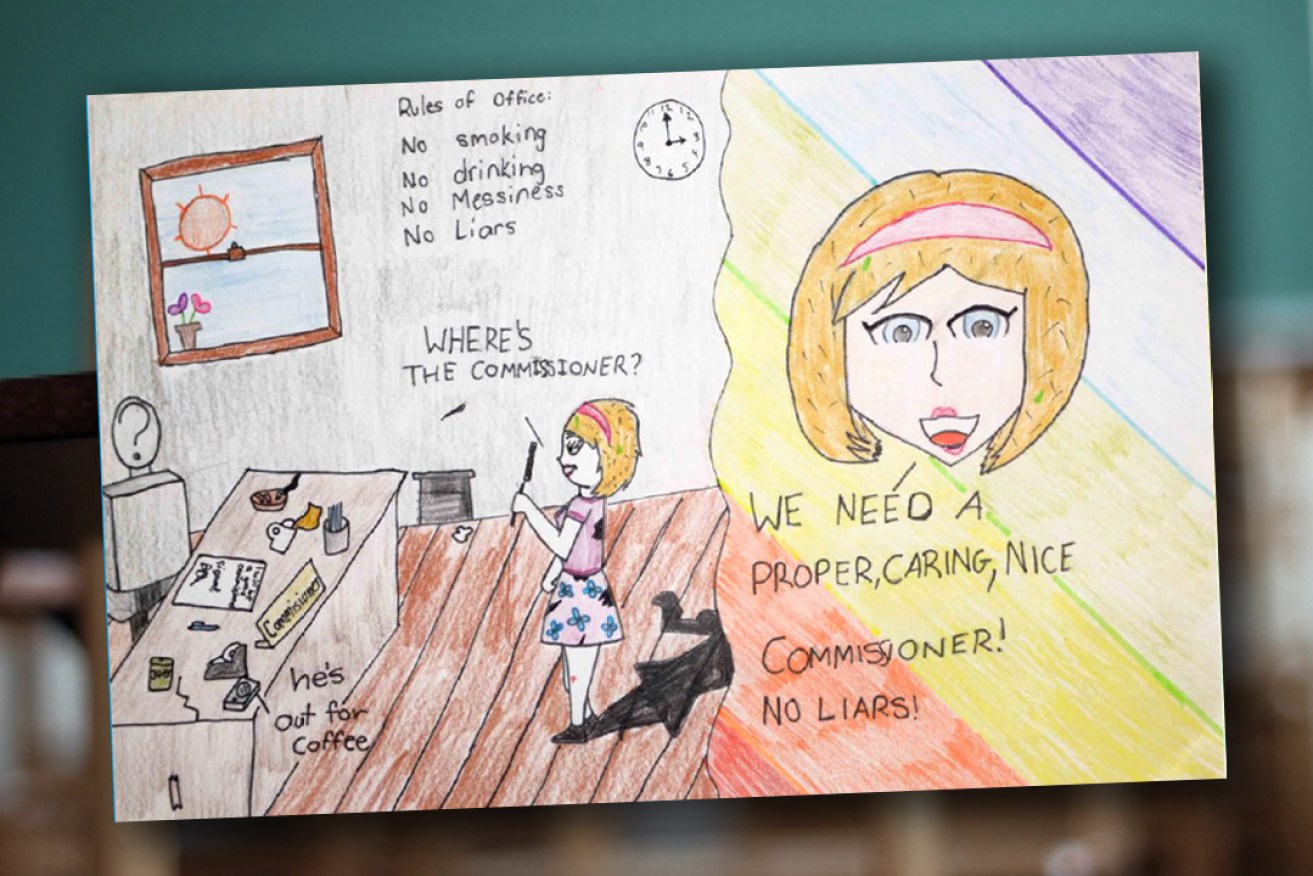

“Not surprisingly, the Council’s 2015 recent conversations with 1,654 children and young people aged 4-18 years indeed found they most want the Government to legislate for a Children’s Commissioner who they can trust and who will listen to them, take them seriously, and use their feedback to educate everyone about what kids need to grow up safe, happy and healthy.”

“Our new book advocates for giving children a greater say in matters that concern them,” says Adjunct Professor Shute, from Flinders’ School of Psychology.

“The issue of children’s rights has become very important internationally in recent years, and many countries from Namibia, Zimbabwe to Austria, Ireland and New Zealand, have well-established children’s parliaments that can put children’s concerns on the national agenda.”

Having the State legislate for an official to uphold the rights of children and young adults is paramount. SA could even become the first Child and Youth Friendly region in Australia.

“Our research into matters such as bullying has shown the value of listening to children’s perspectives,” Professor Shute says.

For example, adults often believe physical bullying is the worst kind, but young people report being more hurt by psychological attacks such as rumour-mongering and cyberbullying.

“South Australian young people have told the Council that feeling safe at school, at home and in the community are paramount, along with the right to education, privacy, respect, belonging and being listened to,” she says.

Many wider issues are also tackled in another 2016 publication Mental Health and Wellbeing through Schools: The Way Forward (edited by Shute and Slee).

Flinders University will host the inaugural Student Wellbeing and Prevention of Violence Conference in Adelaide in July.

The 2015 SA study, entitled “Conversations about rights and a Children’s Commissioner: Listening to the voice of children and young people,” is available online here

Simon Schrapel, chairman of the SA Council for the Care of Children, says it is important for the South Australian model to reflect young citizens’ feedback in the 2015 ‘Conversations’ survey.

“The best examples of Children’s Commissioner legislation provides for broad, systemic advocacy for children’s ‘voices’ to reflect their interests and rights, access to good health care, education, and other services … someone who provides face-to-face contact and is both empowered and free to uphold the best interests of children first and foremost,” Mr Schrapel says.

“Our Conversations project found this is of the utmost importance,” he said, adding the evidence provided further promotes the need to promote South Australia as Australia’s first UN-declared Child and Youth Friendly State.