Ern Malley: How the poet who never lived became the poet who will never die

It’s been nearly 80 years since the infamous Ern Malley hoax yet it is still inspiring new creative works. Samela Harris, who has lived with Ern since she was a child, reflects on how the affair affected her family and left her with the strangest of legacies.

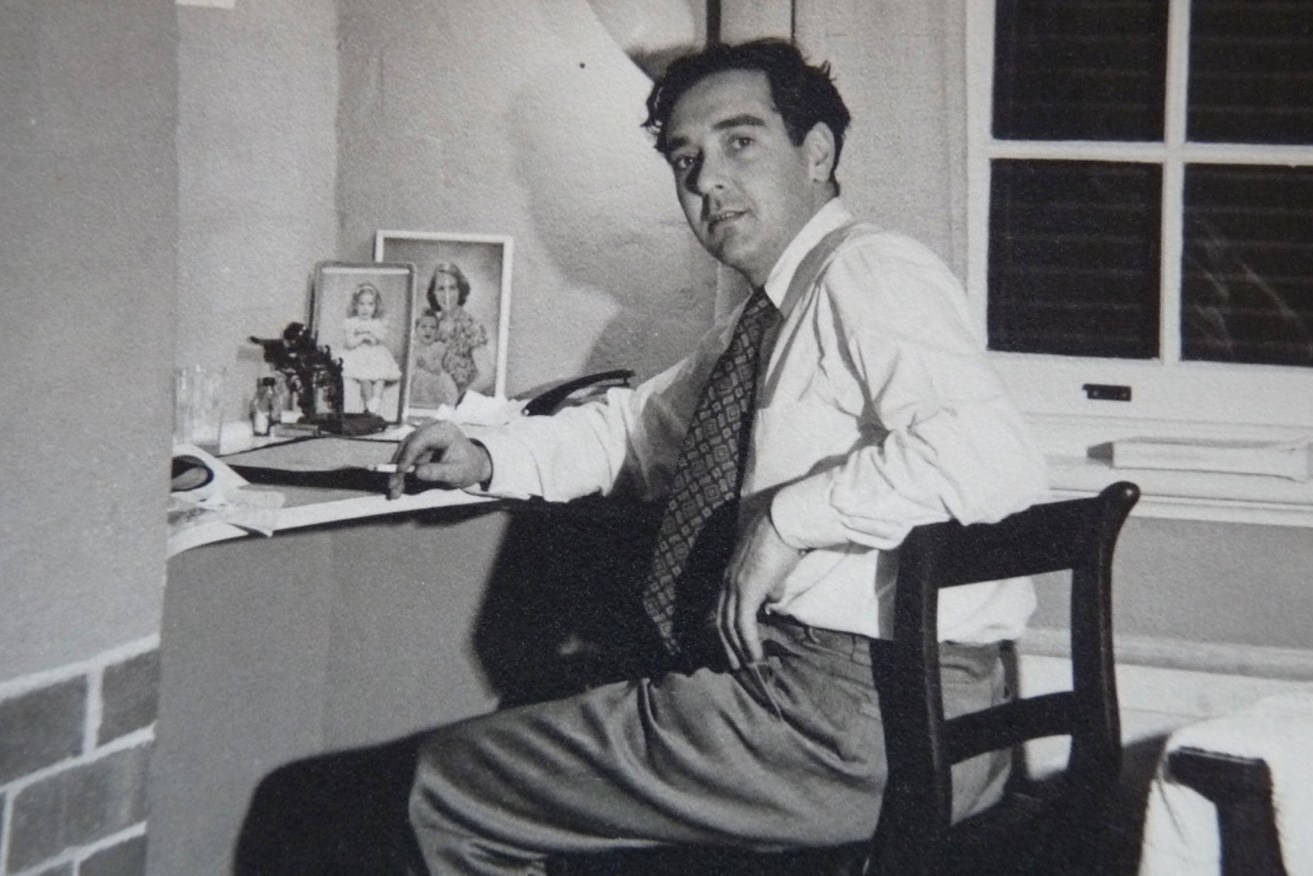

Poet, editor and publisher Max Harris, pictured circa 1949, was pilloried by Adelaide conservatives over the Ern Malley affair.

Ern Malley. Wherever I live, he lives – like a relative who came to stay and will not go home.

I knew his name long before I understood him. How do you explain a vexatious literary hoax to a toddler?

My mother kept him hidden in the bottom of a cedar cabinet like a shameful secret. I was about five when I found him there, in the form a cache of sensationalist newspaper clippings which revealed that in 1944 my father Max had been prosecuted by the police for “obscene advertisements” which were actually poems.

Later, I was to learn that my poor dad, then aged just 23, had suffered days in court defending the hoax poems line-by-line and even defending his own works and views, hammered by an onslaught of philistinism from a constantly-objecting prosecution.

My mother was highly distressed when I asked about my discovery. She denied knowing the clippings cache was there. She said my father’s friend, business partner and family insider, Mary Martin, had collected them during the trial.

Next time I looked in the cabinet, they were gone, never to be seen again. But, for me, Ern was out.

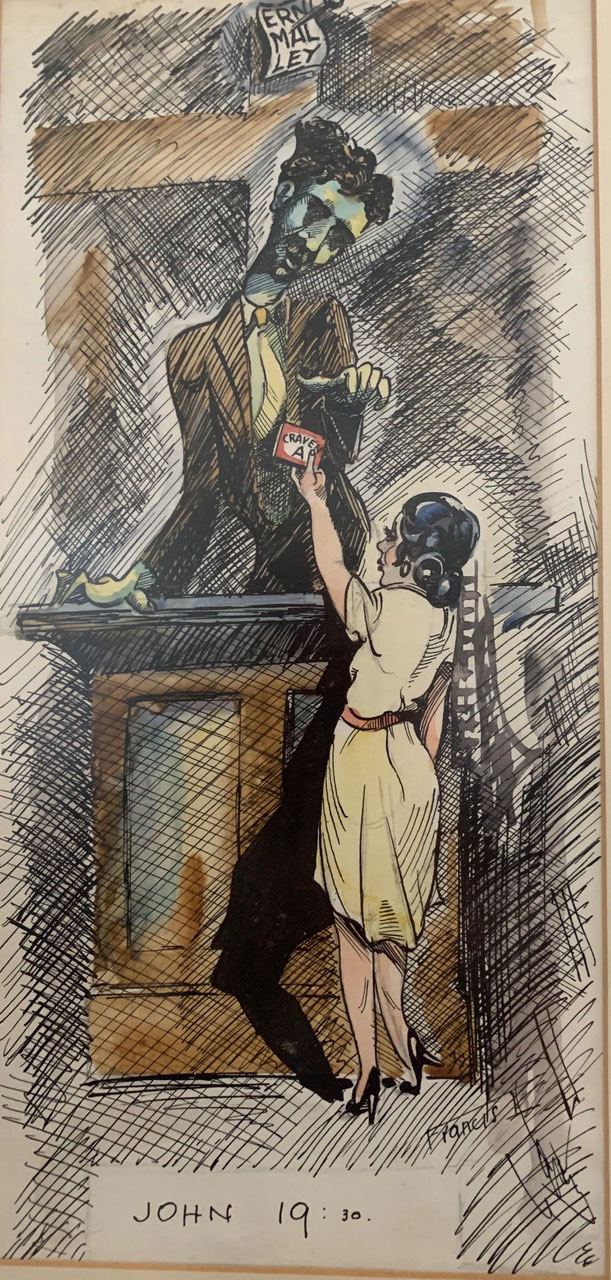

An Ivor Francis cartoon from Max Harris’s trial. Francis, a member of Angry Penguins modernist community, depicted Max’s crucifixion with what they called “the Senorita” offering him his favourite cigarettes.

Not that either of my parents wanted to talk about him. The Ern Malley Affair had been a terrible public humiliation for Max. He was pilloried by the super-conservatives of Adelaide. He had been fooled by two snide soldiers trying to make a mockery of modernist literature, the likes of Dylan Thomas, which was being published in Angry Penguins, the literary periodical produced by Max and his fellow modernists originally from Adelaide University. They stood for everything feared and despised by “the old school”.

Like the hoaxers, Adelaide people were predominantly straightlaced, narrow-minded, judgmental and of meat-and-three-veg mentality in the 1940s Oh, how they loved bringing down that handsome tall poppy of the modernist movement.

My mother remembers people actually spitting on her on the street.

So, it was into the wake of these traumas that I was born. The Ern Malley Affair was infamous.

Well, 78 years later, it is still infamous and I quietly grieve for the enduring pain it caused my late mother, Von.

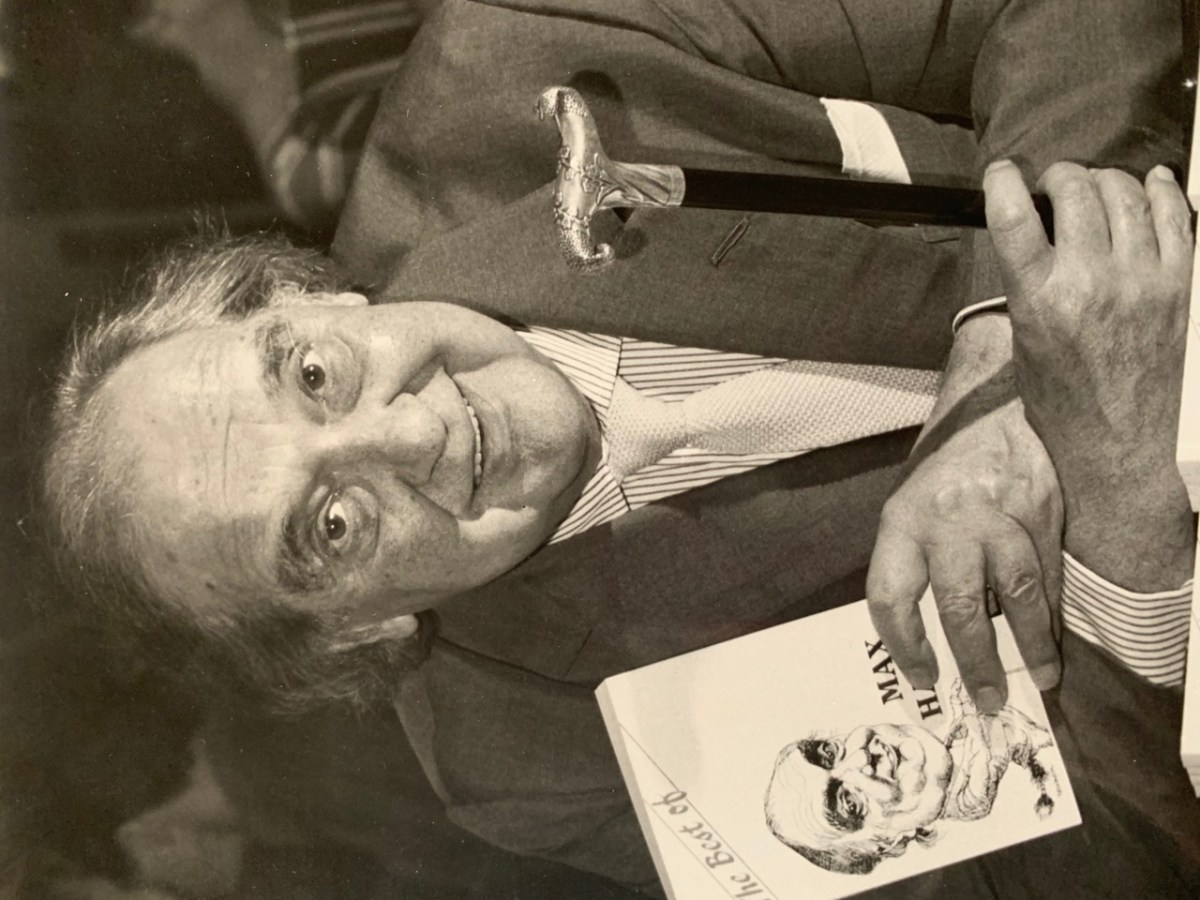

Max, however, who was possessed of a prodigious intellect and a supremely positive outlook, simply stuck by his judgment of the poems. Obloquy be damned. The hoaxers had inadvertently written the best works of their lives. The Ern Malley poems were brilliant. He stood by this belief until his last breath in 1995. And, his judgment of the poems had been endorsed by some of the world’s literary greats of the day, while evidence given in court by Detective Inspector Vogelsang made inadvertent comedy of the very basis of the prosecution by saying such things as “I don’t know what the word ‘incestuous’ means, but it sounds indecent”.

That court-case transcript reads like a weird black comedy.

Max lost, was fined five pounds, and was to live the rest of his life renowned as the raison d’être of Australia’s greatest literary hoax.

But, if he was vilified then, he has been vindicated ever since.

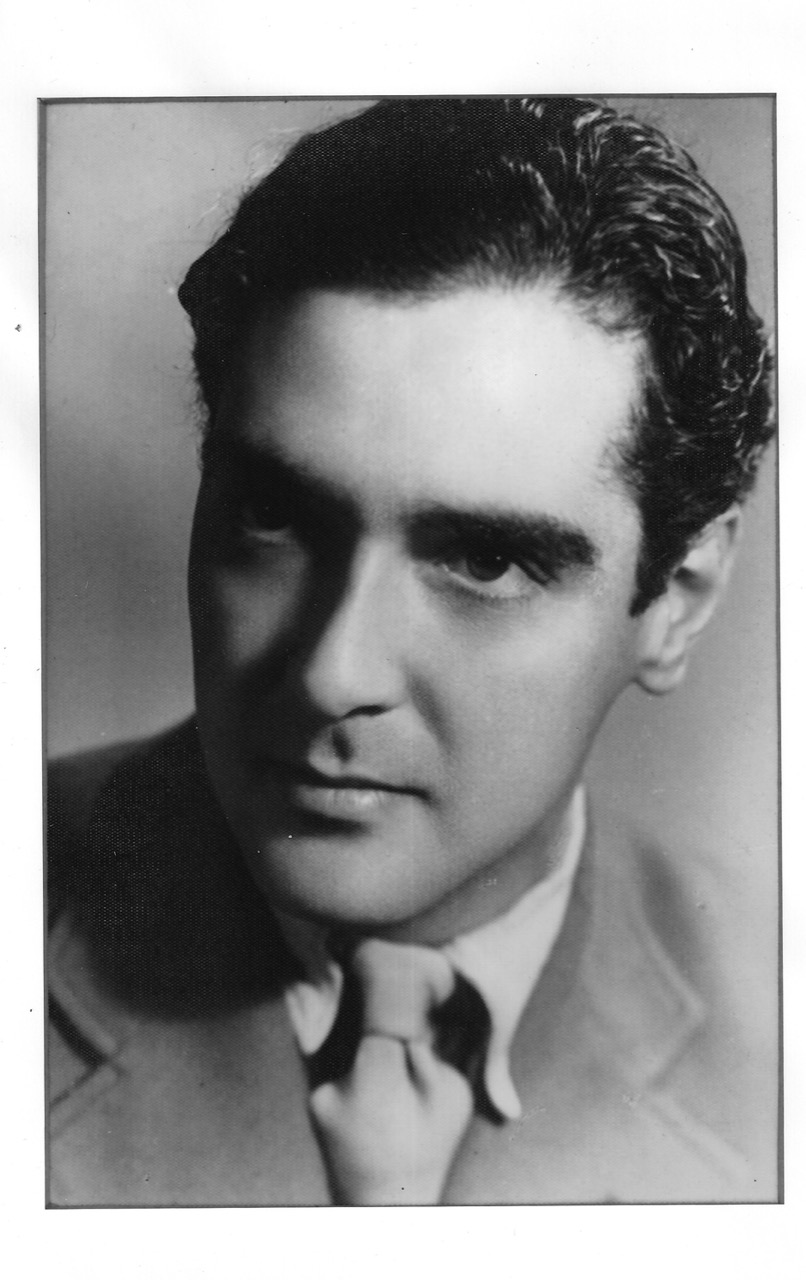

Young Max Harris was the handsome tall poppy of the modernist movement.

Ern Malley, the poet who never lived, became the poet who will never die.

Many times I asked Max to extrapolate on the Ern Malley experience.

One thing he made clear to me. He believed the conservative poet AD Hope was the real figure behind the hoax. He had lashed Max with a ferocious excoriation in reviewing his early surrealist novel, The Vegetative Eye, and as a friend of the hoaxers, Hope was cited as urging them to “Get Maxie”.

And thus inspired, the two soldier poets sat about with their random reference books and knocked up 16 accidentally stunning surrealist poems. Max never believed the hoaxers’ claim that they wrote them in just a few hours. It was a carefully executed plot, complete with the late Ern’s concocted life story and an ingenuous submission letter from his sister, Ethel.

Sometimes Max seemed world-weary at being saddled with Ern. He noted an intellectual parasitism among those who kept interrogating him on it. But he could laugh about it. Launching one reprint of the poems in 1988, we had actors Henry and Emma Salter impersonate Ern and Ethel. With his ever-ready wit, Max was a thriving participant in the Ern celebrations.

In the abstract, however, Max was interested in the “mythologising” of Ern Malley and the way in which his having been “a gullible victim” had seeped into the Australian psyche and how the Ern phenomenon had grown as a creative catalyst for writers and composers.

He always kicked himself for not picking up on the hints James McAuley had left for him. He pinned a postcard with a clue above his desk to enjoy the picture and missed the clue. Of the two hoaxers, it was with McAuley that there was final rapprochement. He seemed the calm one, the one with regret and compassion. Harold Stewart, on the other hand, seemed to burn with anti-modernist hatred for the rest of his life. I always thought it incongruous that he ended up as a Buddhist. Max forgave the hoaxers but Stewart’s ongoing agenda mystified me. Still does.

It was McAuley who, when the issue of copyright came up, wrote to Max on behalf of them both, saying: “We did not put our names to the poems when we wrote them and we won’t now.”

Max always said that Ern was a strange “unlucky penny”. He was an historical cultural entity to be “husbanded” carefully, to be protected and respected. He had never made money, quoth Max, and nor would he, ever.

And thus Ern came to me, under the wing of ETT Imprint publisher Tom Thompson in Sydney. We ensure that he is respected and, if his words are to be quoted, that the attribution is correct.

It has to be the strangest of all legacies.

Max had a positive outlook and always stood by his belief that the Ern Malley poems were brilliant.

Max had been a boy wonder. He could read when he was barely a toddler and his bombastic father would show him off by making him read the racing form guide aloud to his boozy country mates in the pub. Max’s first precocious poetry was published by Possum’s Pages when he was wee. By the time he was about nine he had read (and remembered) the entire Mount Gambier library from A-Z before (against his father’s wishes) winning the Vansittart scholarship to St Peter’s College.

Even in Adelaide at Saints, the handsome young poet was an outsider. He shone as a rover on the football field mainly, he later told me, to keep the bullies at bay. He was bullied at school and even at university when the engineering students famously threw him into the Torrens. With a tousle of wavy black hair and chocolate-velvet “bedroom” eyes, he was the avant-garde highbrow voraciously reading and writing.

Even in Adelaide at Saints, the handsome young poet was an outsider. He shone as a rover on the football field mainly, he later told me, to keep the bullies at bay. He was bullied at school and even at university when the engineering students famously threw him into the Torrens. With a tousle of wavy black hair and chocolate-velvet “bedroom” eyes, he was the avant-garde highbrow voraciously reading and writing.

Soon he was a member of the creative clique producing the university’s Phoenix literary magazine and a founder of the Angry Penguins modernist literary and arts periodical which was to spark Ern Malley into being. Max was driven by an urge to champion intellectual debate and literary creativity.

Angry Penguins was at the vanguard of the new modernist movement in art and literature. The daring international content of the magazine so impressed Melbourne publisher and intellectual John Reed that he lured Max to Melbourne and into the eyrie of his world with Sunday Reed, Sidney Nolan, Bert Tucker, John Perceval, Arthur Boyd, and Joy Hester. There, the publishing company Reed & Harris was born, and Heide was where I was to be conceived.

The “discovery” and subsequent sensational exposure of Ern Malley was to throw that interesting Heide arts hub into a bit of turmoil. Max bravely offered to take the fall when the police threatened prosecution. Reed and Nolan supported his belief in Ern. Sunday had reservations.

It was terribly bleak for our Max. He was incredibly brave and articulate in the face of the ensuing witless anti-intellectual onslaught.

My mother’s football star and dentist father forbade her from attending the trial, which was held in Adelaide, the official business address of Angry Penguins. He saw gentle Max as a scurrilous bohemian. Von had done her best to conceal their love, sneaking out by night to call him from phone boxes, moving to Melbourne as a Borovansky ballet student to be with him.

My mother’s soul bled for the ordeal inflicted on Max back then. She never got over it.

It has been nearly 80 years and the poet who never lived is more alive than ever. It was an Adelaide story then and it still is. History is still being written about him – exemplified by the arrival of Adelaide author Stephen Orr’s reimagining in the novel Sincerely, Ethel Malley and in musician Max Savage’s thrillingly improvisational Cabaret Festival “operatic tour de force”, Ern: Australia’s Greatest Hoax.

The hoax poems continue to be analysed and celebrated, unlike anything else the two hoaxers ever wrote. Poetic justice?

Sincerely, Ethel Malley, by Stephen Orr, was published by Wakefield Press last month (read an extract on InReview here). Ern: Australia’s Greatest Hoax, is a collaboration between South Australian musician Max Savage, composer Max McHenry and realist oil painter Josh Baldwin which will be presented on June 24 and 25 at the Space Theatre as part of the 2021 Adelaide Cabaret Festival.

Samela Harris in an old photo with her dad, Max.