You write what? In defence of romance

Romance novels are a $1 billion industry – a market-dominating genre written by women, for women, about women. So you should think twice before wrinkling your nose at love, writes Adelaide author Amy T Matthews.

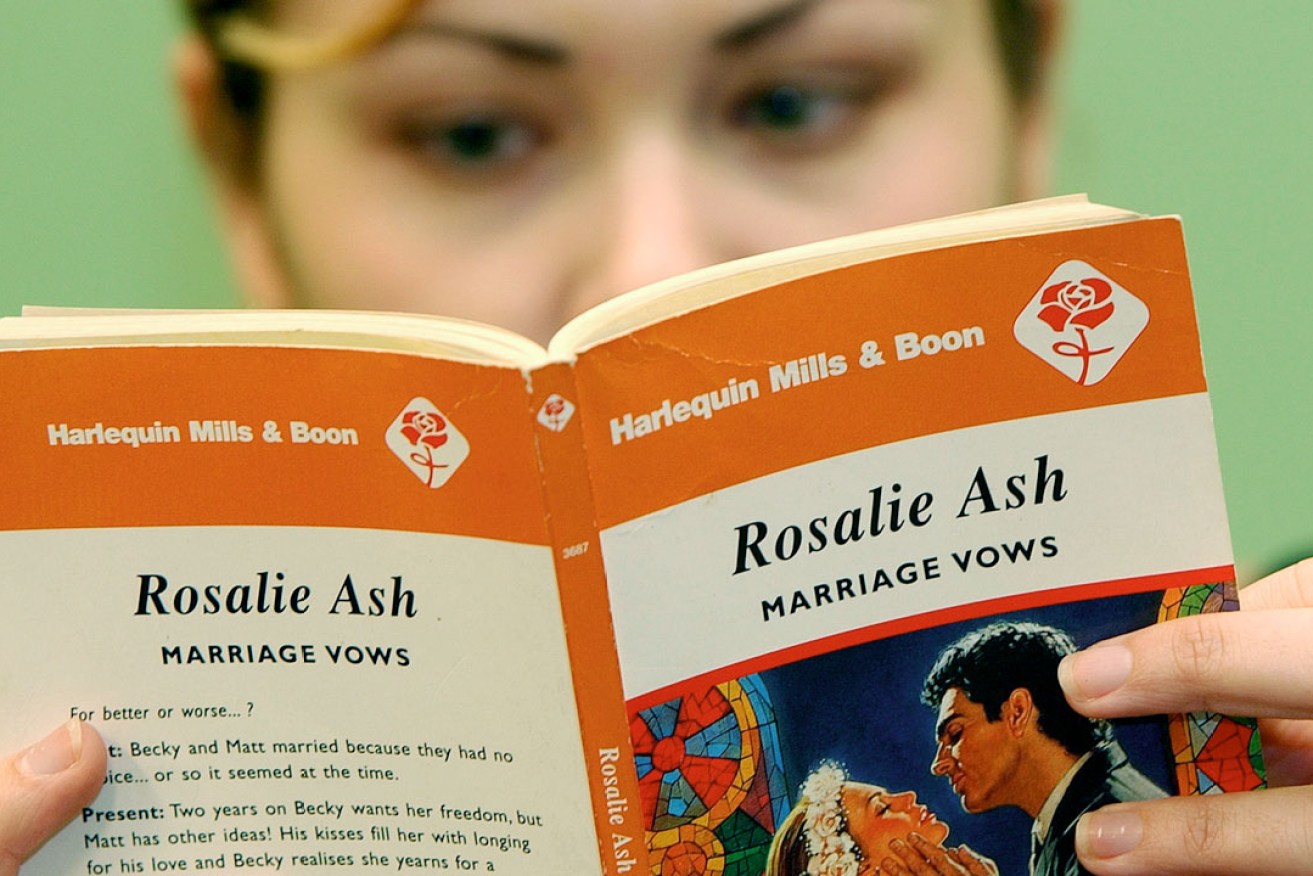

All kinds of women - and some men - read romance novels. Photo: AAP

“So, what do you do?” It’s the standard small-talk question, fired at dinner parties, cocktail parties, training sessions, conferences, events at the kids’ schools. Basically any time you meet someone you don’t already know.

“I’m a writer.” That’s simple enough. But I brace for the next question.

“What do you write?”

Ah, now. There’s the rub. Which writer should I be for you? The award-winning literary novelist? The one you’ll treat respectfully and be mildly impressed by, even if you’ve never read a word of it? Or the romance novelist? The one you won’t be able to help wrinkling your nose at?

Like most writers, I’ll be whichever one has a current book to spruik, even if it means I have to put up with a nose wrinkle or two.

I know you don’t mean to do it. But your mind goes to Mills & Boon and your nose wrinkles right up. Because anyone could do that. Right? Besides, it’s sexist nonsense. Pap to keep women happy.

Germaine Greer said that all the way back in the ’70s, didn’t she? She crankily dismissed romance readers (and writers), as women who were “cherishing the chains of their bondage”.

And it’s just porn for women. Isn’t it? Look at that Fifty Shades of Grey, it’s rubbishy smut. And so badly written! You could write that in your sleep. Blindfolded. It’s not a real book.

Don’t worry. We get it all the time. The vague astonishment. The distaste. The dismissiveness. And yet… romance accounts for almost 50 per cent of all books sold and is a $1 billion industry. It’s read by women of all kinds (and some men), of all levels of education, by professionals as much as (if not more than) stay-at-home wives and mums. Teenagers read it and octogenarians read it. And it’s as progressive as it is conservative.

Progressive? You wrinkle your nose again at that. It’s okay. I don’t judge you for it. Everyone does it.

This is usually where we’ll get another glass of wine, if we’re somewhere that’s serving wine. Because we’re both interested in this and we both enjoy conversations that get good and feisty.

How on earth can those kinds of books be progressive, you ask as you get your fresh glass. They’re all about women getting married, about limp heroines getting swept off their feet by alpha males. Aren’t they?

Yeah, not so much. Since they were the first thing you thought of, let’s start with Harlequin Mills & Boon (we call them category romance). There are dozens of different kinds of categories, ranging from the sweet (no sex anywhere to be seen) to the blazingly sexy, and they’re a cultural barometer for women’s issues. In fact, they’re usually ahead of the curve.

There were heroines who were career women long before it was culturally acceptable. There were heroines who were divorcees, single mothers, pregnant women, rape victims, survivors of sexual abuse, survivors of domestic violence – romance believed these women were heroines when the culture at large couldn’t move past them being victims.

Romance novels have dealt with infertility, adoption, step-parenting, the struggle to find the mythical work-life balance and many other issues women face in their lives. Romance takes these things and turns them into heroic journeys.

There’s a lot going on in romance. It’s complex. But our embedded sexism leads us to dismiss it

But come on, you say, what about the fact women have to end up with a man at the end of the book. How can you call them progressive when that happens?

I said they were a mix of progressive and conservative. I agree with the criticism of romance’s heteronormativity, and the fact that most romance features only middle to upper-class white people. But we’ll leave aside those issues for now, even though I think they’re issues that need addressing urgently; the range of human sexuality and romantic experience is visibly under-represented in mainstream culture and I don’t intend to dismiss them indefinitely. But, just for today, let’s talk about the core of the mainstream romance: the relationship between a man and a woman.

Relationships matter. Our culture has been built around the family, with the monogamous heterosexual couple at its centre. So many of us are in a relationship, or longing for a relationship. And these relationships, and hopes for them, occur within a cultural context that has historically devalued women’s roles.

Romance tells women they matter. It matters to be a lover. It matters to be a partner, or a wife. It matters to be a mother. You are valued. That’s the message of romance. More than that: you are central. Not only do you mean something, you mean everything.

The conservatism of the genre reflects the culture, as does the progressiveness. What we see in romance is the dynamic we see in the culture; we see the tension between traditional expectations of women and their drive to break free of those expectations since second-wave feminism.

“But you write proper books too?”

There’s always a point where you’ll get bored and shift the conversation, and that’s usually the next question you’ll ask. You’ll be more comfortable talking about my “serious” books, even though fewer people probably read them, and I think of them as less culturally relevant (in some ways) than the romances. You’ll shift the conversation because you get bored, or because you don’t really buy what I’m saying. Because no matter what I say, they’re not “proper books”.

And there we have it. That’s what we live with as women. A genre written by women, for women, about women, which dominates the market, is dismissed off-hand with the wrinkling of a nose.

There’s a lot going on in romance. It’s complex. But our embedded sexism leads us to dismiss it, without ever really taking the time to think about it.

Almost $1 billion in sales every year. All those women around you are buying those books. Why?

Because they matter.

Amy T Matthews is an award-winning novelist and a lecturer in creative writing at Flinders University. Matthews’ novel End of the Night Girl won the Adelaide Festival Unpublished Manuscript Award; it was also long-listed for The Australian/Vogel literary award, and short-listed for the Nita B Kibble Dobbie Award and the Colin Roderick Award. Her alter ego Tess LeSue writes historical romantic adventure stories. Her latest book, Bound for Eden, was released this month.

Matthews is organising the academic University of Love conference stream at the Romance Writers of Australia national conference in Adelaide next month.