Explained: Petrol prices are smashing records, so why isn’t fuel tax on the agenda?

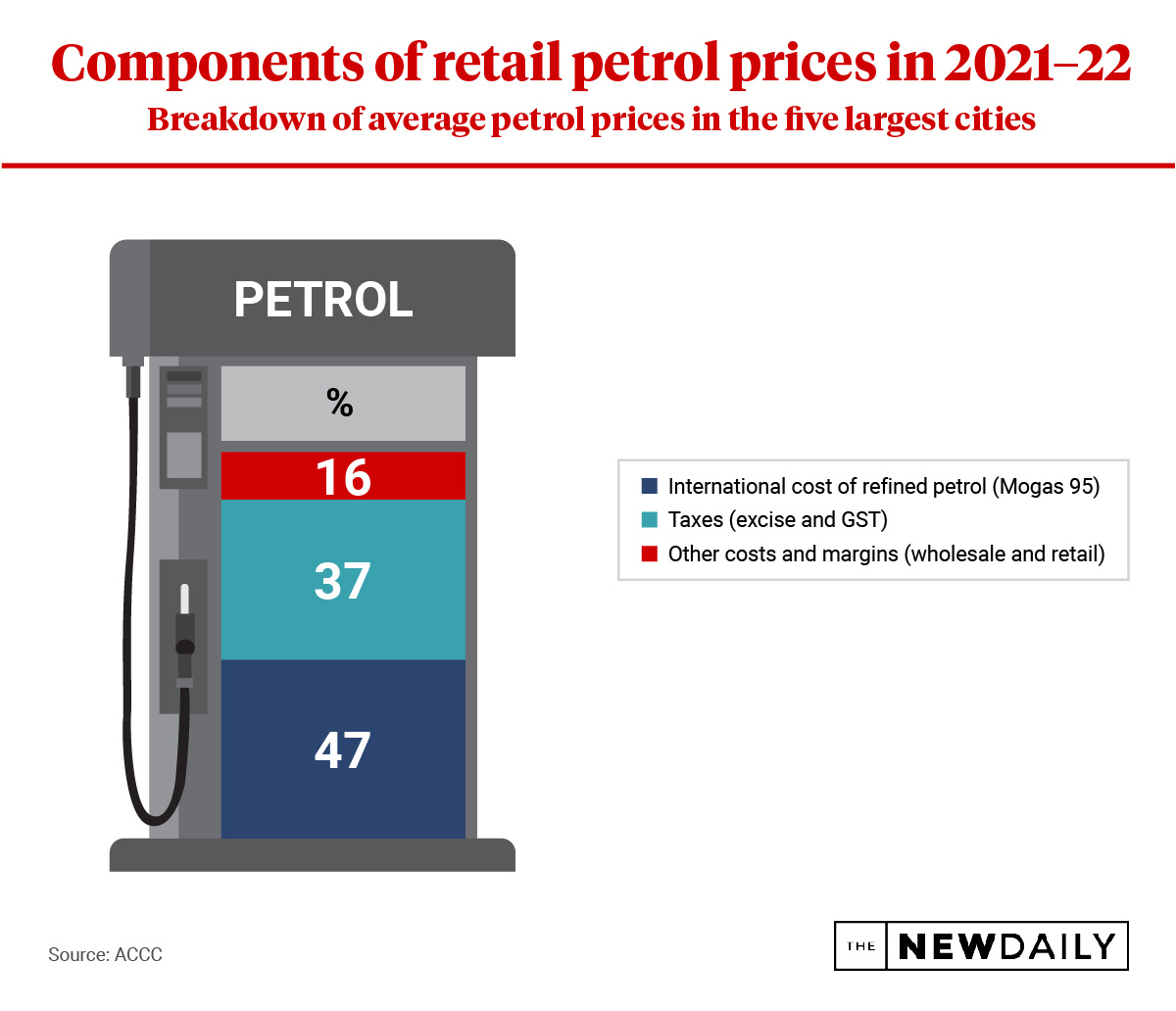

Global oil prices are typically blamed for rising fuel prices in Australia – the latest hikes have seen petrol prices approach $2 a litre. But more than a quarter of the price is tax and it just went up.

Photo: AAP

In 2001, former prime minister John Howard was forced into an embarrassing retreat after admitting he didn’t understand how rising petrol prices were squeezing Australians.

Bowser boards were rapidly climbing towards $1 a litre for the first time in Australian history, and, with an election coming, Howard conceded he was “plainly wrong” in earlier refusing to ease fuel taxes for motorists.

There’s no such contrition on the table these days – Scott Morrison flatly ignored a question about pausing twice-annual rises in the $12 billion fuel excise this month, and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg is mum on the issue as well.

Last week, some motorists in Brisbane were coughing up almost $2 a litre for petrol, a fresh record that The New Daily would typically cover by explaining the reasons behind rising global oil prices, a factor over which Morrison has little control.

But it’s often forgotten that more than a quarter of the price is driven by something the government does control: Tax. And it just went up.

You’re now paying 42.2 cents for every litre of fuel in your vehicle, and before the end of the year it will rise again in line with inflation as the government has no plans to reduce the tax.

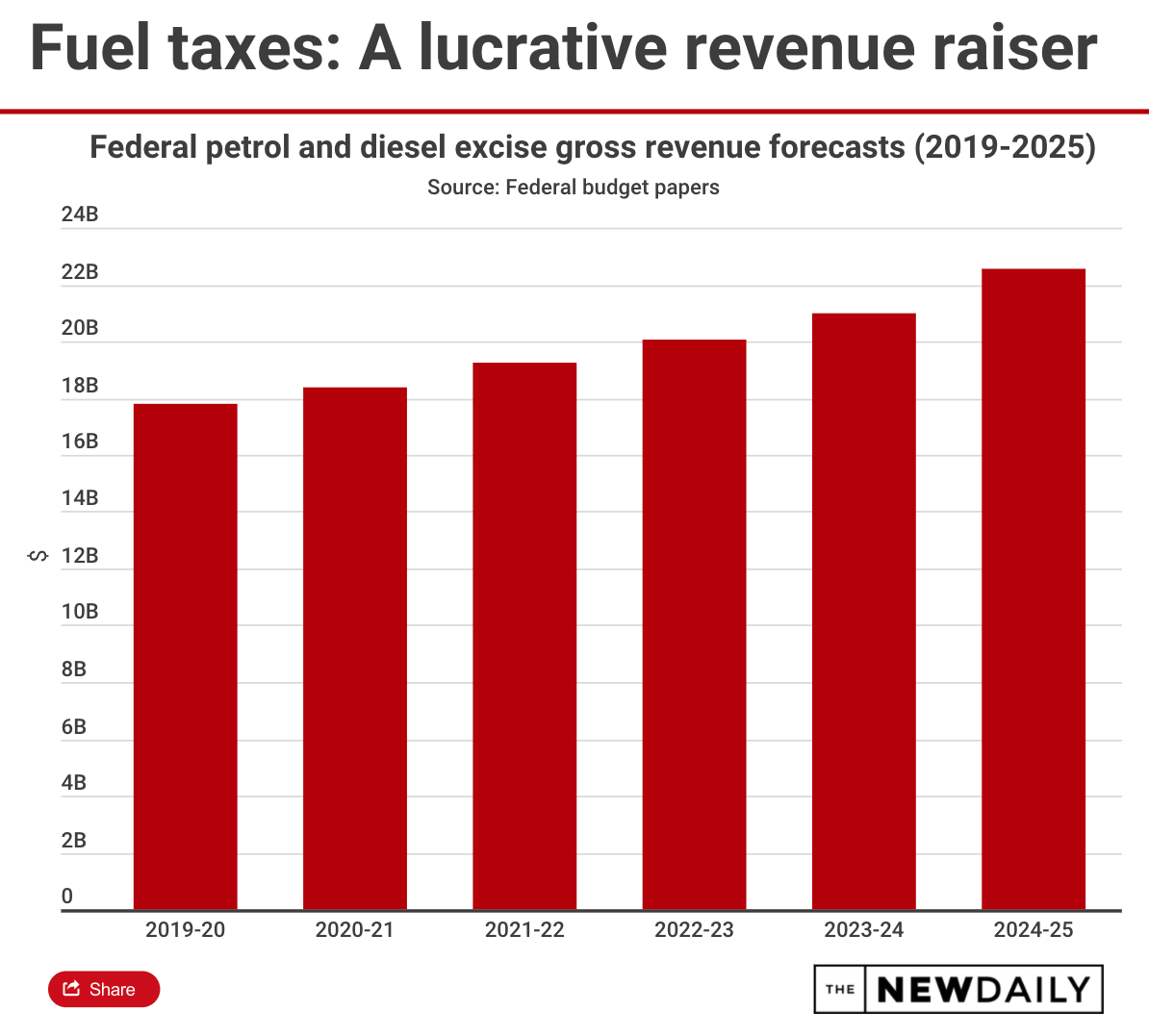

These inflation ‘indexations’ help make fuel excise one of the most lucrative taxes at the Commonwealth’s disposal in the fight to pay off its COVID-19 debt.

And perhaps that’s why neither major party wanted to talk about the tax when asked by TND to comment on its effect on households, despite the impending election slated to focus on the rising cost of living, of which the petrol squeeze is by far the most serious.

Experts say we’re overdue a conversation about it, though, because over the next 30 years the excise will fall into terminal decline as motorists adopt electric vehicles, leaving a huge hole in the budget for whichever government is in charge.

How much fuel tax you pay and why

First, some history.

Australia has taxed fuel for decades under the proviso of funding road infrastructure and maintenance.

But these days the money isn’t tied to roads – instead, it flows into general government revenue like most other federal taxes.

The average motorist paid about $775 in fuel excise in 2021, based on 35 litres a week in petrol purchases. Tax is about a third of our fuel bills.

Fuel excise is a regressive tax, because poor workers cough up a much greater proportion of their income paying it than rich people do.

But this tradeoff is accepted by economists, who say consumption taxes like this are an efficient way to pay for schools, roads and vaccines.

University of New South Wales Professor Richard Holden said motorists wear down roads, create congestion and emit pollution when they drive and should pay for these negative “externalities” through higher taxes.

He said the outsized burden the fuel excise places on workers could be addressed in other ways under Australia’s largely progressive tax rules.

“If we want to address budget pressures on households, then we should address those by reducing other taxes or by giving other subsidies to households,” Professor Holden said.

“Encouraging people to drive more doesn’t seem like the best way.”

Grattan Institute transport and cities program director Marion Terrill agreed with that assessment, adding that the fuel excise is also seen as a de-facto carbon tax.

In fact, the Australia Institute estimates that when Howard paused the fuel excise in 2001, it created an extra 16 million tonnes of carbon emissions because driving around became comparatively cheaper.

“[The fuel excise] does sort of operate that way given we don’t have an economy-wide carbon tax,” Terrill said.

“But that’s not the reason we’ve got it.”

The bottom line is that you’re paying fuel excise because governments need money and consumption taxes are an effective way to earn it.

They’re difficult to evade and everyone who drives must pay them.

Well, almost everyone.

‘Doesn’t make sense’: Australia’s big fossil fuel tax break

Some of Australia’s largest and most profitable businesses are actually able to claim their tax bills back under a controversial rebate scheme.

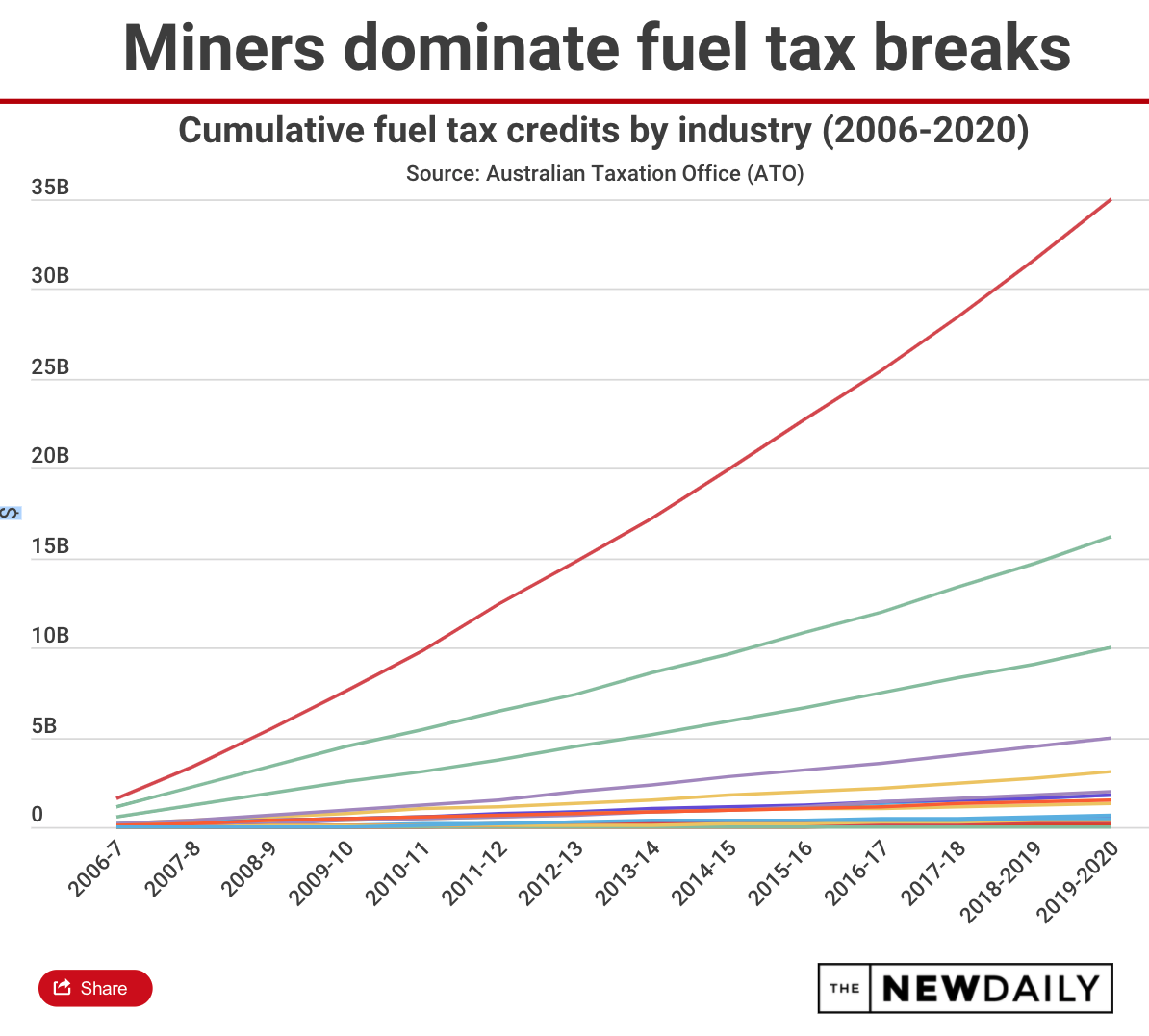

In total, $7.8 billion was paid out in fuel tax credits in 2019-20, which is more than was set aside for the navy in that year.

The Australia Institute calls it our largest fossil fuel tax break because key beneficiaries are oil, coal and gas giants, who claimed $14.5 billion in fuel tax credits between 2006-2007 and 2019-2020, public figures show.

Businesses and the government justify the rebates by noting their vehicles don’t use public roads.

A coalition of mining and agriculture lobbyists celebrates the credits as good for independent farmers.

But agriculture rebates are dwarfed by Australia’s massive mining sector.

Miners, including giants like Rio Tinto, claimed $34.9 billion in rebates over 14 years to 2020 – more than three times every farmer combined.

Terrill said the way these rebates operate are also “quite arbitrary”.

She said that because fuel excise isn’t directly tied to road funding, rebates can’t exactly be justified by whether a firm uses public roads.

Other negative side effects also occur regardless of where vehicles are driven or diesel machinery is used, most notably pollution.

“You get rebated if you are a particular kind of road user, but it’s quite arbitrary in how it works,” Terrill said.

“If your heavy vehicle is more than 4.5 tonnes you can claim a credit, but if you have a smaller rigid truck you can’t … it doesn’t make sense.”

Professor Holden is also critical of rebates, saying diesel credits should be “abolished”.

Australia Institute research director Rod Campbell said scaling back fuel tax credits to fossil fuel giants could allow the government to ease the tax burden on motorists without reducing government revenue.

“It’s entirely possible for the government to wind back, to a large degree, what turns into a subsidy for the mining industry,” Campbell said.

“It’s pretty weird to us that the coal industry doesn’t pay this tax whereas a nurse or tradie that drives to work does.”

Australia’s doomed tax

Campbell said reforming the excise will become increasingly urgent as Australia faces international pressure to improve emissions targets.

The New Daily asked Treasurer Josh Frydenberg and shadow energy minister Chris Bowen about the excise, but neither politician answered questions about it.

Experts said the tax has been thrown into the ‘too-hard basket’ because its future is mired in uncertainty, with the transition to electric vehicles set to dramatically reduce the use of petrol.

Terrill and Professor Holden both agreed the fuel excise is facing a terminal decline over the next 30 years as the nation reduces its carbon emissions, creating a $12 billion annual hole in the federal budget.

This problem has been understood for several years – The New Daily covered it in 2019 – but Terrill said little has been done at the federal level to prepare for the transition to electric vehicles (EVs).

Alternatives do exist, though.

Road-user charges, which tax motorists based on the distance they drive, have long histories in nations like Singapore and are much more transferable to electric vehicles than fuel-based taxes.

But unlike Singapore, the federal government is part of a federation, which creates some thorny issues.

Terrill said Australia’s constitution does not allow the Commonwealth to discriminate against taxpayers based on where they live, which is something a road-user charge arguably does because it is based on where people are driving.

And so this means state governments might have to take the lead on road tax over the next three decades.

In fact, Victoria is already charging a road-user charge for EVs, but Professor Holden said the positive side effect of drivers switching to clean vehicles shouldn’t be forgotten.

“We want to encourage the uptake of electric vehicles, and so I would prefer not to have a road-user charge right now,” he said.

“But we will have to end up with one once you can’t buy a petrol car anymore.”

This article was first published in The New Daily. Read the original article here.