Experts divided on housing crash predictions

Two of Australia’s major banks have this month foreshadowed the biggest housing market price crash in decades but experts are split on the prediction’s accuracy.

There has been a big change in the outlook for house prices in the past week.

After two years of rapidly rising prices, most homeowners have gained more wealth from their property than their jobs since COVID-19 started, with house prices skyrocketing more than 25 per cent in 2021 alone.

But Commonwealth Bank and National Australia Bank now argue this record-shattering run is about to unravel into the biggest housing crash of our generation.

Economists at both banks are predicting a 10 per cent fall in house prices next year, on the back of an expected interest rate hike by the Reserve Bank.

Commonwealth Bank senior economist Belinda Allen said the market is headed towards a significant “cooling”.

“We have already seen fixed-rate mortgages move higher in recent months as well as the implementation of the higher interest rate serviceability buffer by APRA on November 1, 2021,” she said.

“Both will assist in cooling the market.”

NAB chief economist Alan Oster has a similar view, forecasting that the 10 per cent fall in 2023 will follow a 3 per cent rise in 2022.

“We see this as a relatively orderly decline,” NAB chief economist Alan Oster said.

“It is important to remember this correction comes after a very sharp run-up in prices over the last year.”

Westpac economists are also predicting falling house prices in both 2023 and 2024 after the RBA lifts the official cash rate.

Will house prices plunge?

These forecasts imply the median national property price will fall by about $73,000 next year, based on the latest CoreLogic data.

That would be the biggest housing downturn in modern history, according to housing economist Andrew Wilson.

The last time property took a downward turn was in 2018, when prices plunged by about 5 per cent.

It drove headlines like: “Prices fall at the fastest rate in 30 years”.

Prices also fell 4.8 per cent in 2011 after a period of post-global financial crisis rate rises from the Reserve Bank.

Dr Wilson said those falls pale in comparison to what banks now predict.

“These are quite remarkable forecasts,” he said.

“Historically we’ve only had three years of falling prices since 1987.”

It’s worth paying attention to what the big banks think about housing because they have a lot of money tied up in the property market.

But buyers agent Arjun Paliwal, who is head of research at InvestorKit, said the banks are often wrong about it.

A recent example was when the big banks predicted a dramatic property crash in early 2020, before the market did quite the opposite and prices soared.

“Banks don’t have a great track record with housing,” Mr Paliwal said.

He argues that low unemployment, falling housing supply and an influx of migrants as borders reopen all point towards higher prices in 2023.

“The idea all these things equal prices going down stumps me,” he said.

“Even if the cost of money [interest rates] trends up slightly, it should be going up with other things like wages growth.”

Dr Wilson is also sceptical about forecasts of a housing downturn.

He said the banks think higher interest rates will drive prices lower because they will constrain buyers’ borrowing power.

But historical data shows it takes a while for housing prices to respond to higher rates.

“When we see house price reductions it comes after a sustained period of higher rates,” Dr Wilson said.

“The falls tend to be quite moderate.

“Prices usually rise faster with lower rates than they fall with higher rates.”

The Reserve Bank, which is responsible for whether interest rates rise, has also played down a 2022 rate rise and suggested that if it does hike rates such moves would be incremental.

Key to the timing will be the pace of wages growth, which RBA governor Philip Lowe says must rise above 3 per cent in annual terms before conditions are ripe for higher interest rates.

Two-speed housing market emerges

Mr Paliwal said current housing market conditions point to higher prices.

But price growth is slowing as a two-speed market emerges, he said.

Basically, the market is balancing out in Sydney and Melbourne, making conditions better for buyers and worse for sellers than it has been during the pandemic.

“In markets like Sydney and Melbourne, more stock is on hand each weekend and buyers have more choice,” Mr Paliwal said.

But in other cities, particularly Brisbane and Adelaide, selling conditions are still improving due to higher demand from those moving interstate.

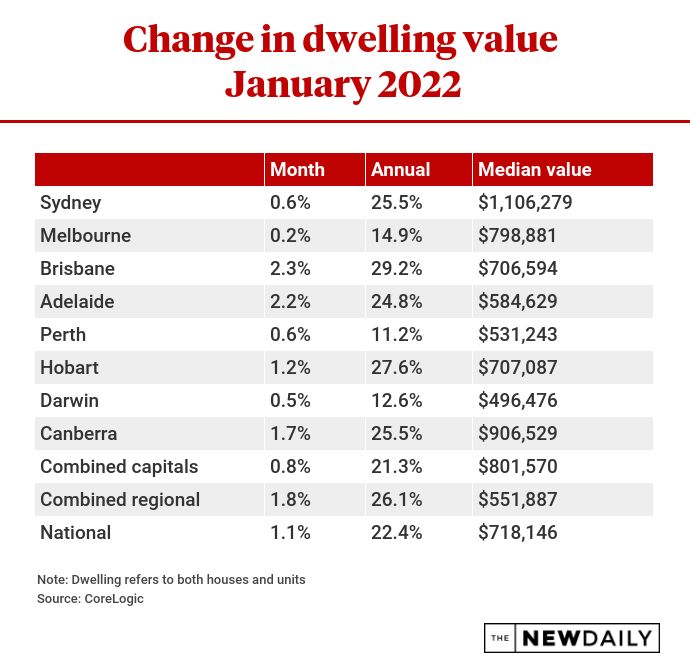

This was seen in the recent January house price data from CoreLogic.

Prices rose 0.6 per cent in Sydney and just 0.2 per cent in Melbourne.

But in Adelaide and Brisbane they rose by 2.2 per cent and 2.3 per cent respectively.

Mr Paliwal said one property in North Adelaide he searched for on behalf of a client last week drew more than 60 offers and 100 visitors to the open house.

It was advertised at $600,000 to $640,000 but sold for more than $750,000.

This article was first published by The New Daily, read the original article here.