Growth and jobs under the Marshall Government, two years in

Ahead of the 2018 state election, Steven Marshall said a Liberal Government would deliver higher economic growth and more jobs. As the Premier prepares to mark his second year in office, we crunch the numbers to assess his government’s performance.

Steven Marshall, pictured on election night 2018. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

In a speech to mark the end of his first year, Premier Steven Marshall noted that his government “took office 12 months ago, with a clear mandate to pursue economic growth”.

He added the notably forward-looking caveat: “… with the right mind-set, there is great opportunity to do so”.

So what do the statistics say about the state of this opportunity?

GROWTH

According to the University of Adelaide’s SA Centre for Economic Studies (SACES), gross state product increased by 2.3 per cent in 2017-18 – roughly in line with the state’s performance in the final year of the Weatherill Government.

And it grew by 1.4 per cent in 2018-19 – roughly, the first year of Marshall’s incumbency.

The latest SACES economic briefing, published in December, suggests growth has slowed further in the current financial year, forecasting gross state product to expand by just 0.75 per cent in 2019-20, with recovery due the following year.

None of these figures have come within 100 basis points of the Marshall Government’s ambitious growth target of 3 per cent per annum.

Treasurer Rob Lucas now concedes that the Marshall Government won’t achieve that ambition within the next 12-to-18 months, at least.

“I think you’ll find most of the estimates for economic growth in Australia across all of the states would be lower than any of us would wish,” he told InDaily.

“That doesn’t mean that we still don’t have an ambition as the Premier’s outlined to grow the state’s economy at three per cent.

“But clearly that’s not going to be achieved in this current 12 month period or the next one.”

Treasurer Rob Lucas presenting the 2019 state budget.

By “the current 12 month period”, Lucas means this financial year.

So, the earliest he thinks three per cent possible is the middle of next year, less than 12 months before the end of the Marshall Government’s first term.

Nonetheless, Lucas argues that the Government has done everything in its power to encourage and sustain economic growth in the face of economic “headwinds” from interstate and around the world – including the international slowdown in part caused by Donald Trump’s trade wars and new threats, like the COVID-19 coronavirus.

The estimates of economic growth are going to be lower in South Australia … that’s just a statement of fact.

He cited reductions in payroll tax, land tax and the Emergency Services Levy as evidence of the government’s efforts.

SACES director Michael O’Neil told InDaily factors outside of the Marshall Government’s control, including the decline of car manufacturing, but especially the drought, have had a big impact on growth in South Australia in recent years.

Drought is currently affecting around 70 per cent of the state, according to Primary Industries and Regions SA, including more than 4500 farming properties – and rainfall continues to be below average.

Total crop production across South Australia was 6.9 million tonnes in 2017-18 and 5.6 million tonnes in 2018-19, compared to the five-year average of 8.3 million tonnes.

The Marshall Government announced a $21 million drought support package in December.

Labor Treasury spokesperson Stephen Mullighan told InDaily that “the major growth engines of the state’s economy are all struggling”, and Marshall Government’s should be doing more to prop up the state’s economy.

In particular, he points to the construction sector.

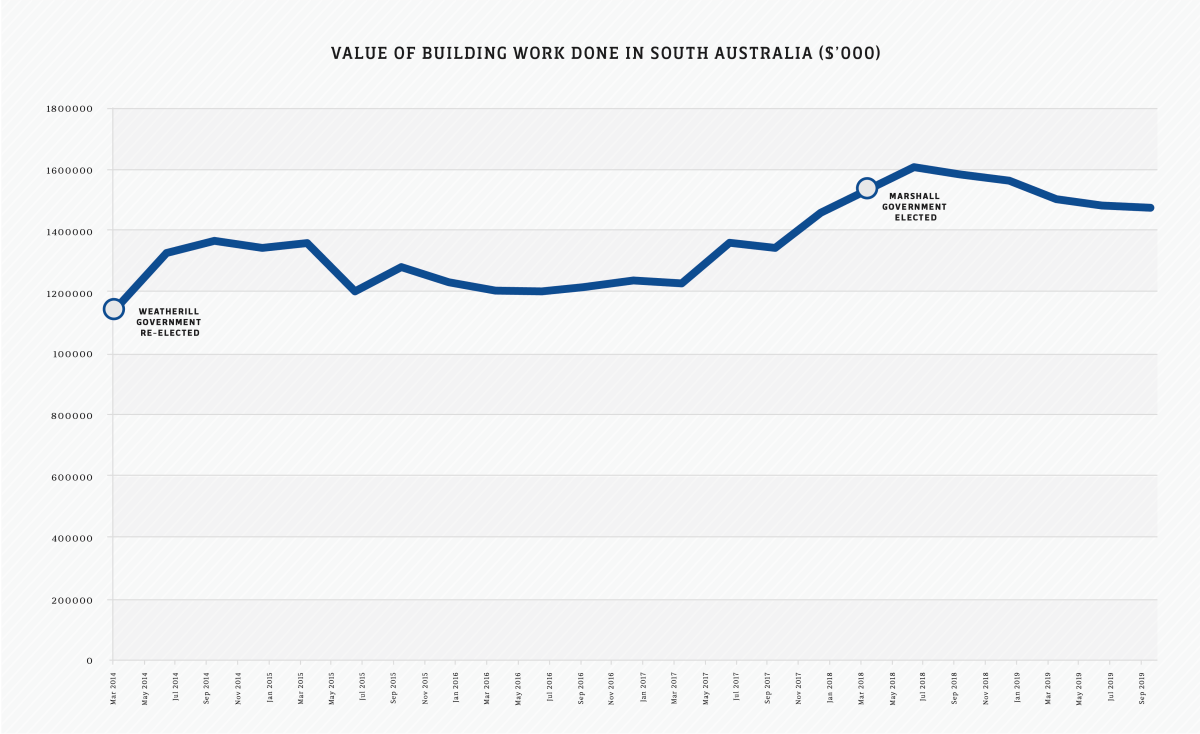

“The total value of building work done … is substantially down,” said Mullighan.

“The Government’s racking up debt, but they aren’t spending that money on … a huge program of infrastructure construction.”

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the total quarterly value of construction work done in South Australia hit a peak of $1.6 billion in the June quarter of 2018 and has been steadily declining since.

But those figures remain substantially larger than those seen during the last term of the Weatherill Government.

Data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, seasonally adjusted quarterly value of building work. Graph: Bension Siebert / Nicky Capurso

Mullighan argued that now is the time for investment in major new infrastructure projects, and that the Government has yet to deliver.

Lucas said that Infrastructure South Australia, the agency set up by the Marshall Government to recommend such projects on the basis of merit, is due to issue its draft 20-year infrastructure plan “this month or next month”, and to release its five-year rolling capital intentions statement before the next state budget.

The Treasurer said he would be paying “very strong respect (and) attention” to the recommendations of that body – although he stressed it was the Government’s prerogative whether or not to accept them.

Overall, in the immediate term, Lucas said he was expecting economic growth to remain soft.

He predicted “a very significant write-down in Australia … as a result of bushfires and coronavirus”.

The impact of coronavirus, he said, would go beyond tourism and international students (Chinese students make up the largest proportion – 40 per cent – of international students in South Australia) to also affect manufacturing businesses that source mechanical parts from China.

“I think people are only just coming to appreciate the impact,” he said.

“In terms of the coming year – 2020-2021 – the estimates of economic growth (are) going to be lower in South Australia, but also in every other state … than any of us would have wished or previously predicted. I think that’s just a statement of fact.

“We’re going to have to work our way through those significant headwinds, but that doesn’t mean you don’t do all the things that you know you have to do to try and drive economic growth … as we promised to do.”

The Marshall Government revealed its “growth state agenda” last year.

Of the nine industries since identified as growth sectors for the state as part of the plan, the Government has so-far produced industry plans for only two: tourism and international education.

“Every other of those is still being worked on – that’s pretty slow for a government that’s been in power for two years,” said O’Neil.

“That’s what the government says it was about … it’s about industry leading jobs growth.

“Surely you should be at the stage of implementation now.”

Lucas said the hold-up was the result of ongoing consultation with the remaining industries: defence; food, wine and agribusiness; hi-tech; health and medical industries; energy and mining; space industry and creative industries.

Mullighan said the Marshall Government’s growth agenda was a reheated version of the Weatherill Government’s “10 economic priorities”.

JOBS

A promise to lower the unemployment rate was key to the Liberal Party’s appeal at the 2018 election.

Analysing the Marshall Government’s performance on jobs against that of the Weatherill Government during its final term presents two obvious problems: many factors outside of the control of any State Government influence the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate – which is, itself, a deceptively complicated metric – and we’re comparing a full term of government against a half-term.

Nonetheless, some clear conclusions can be drawn.

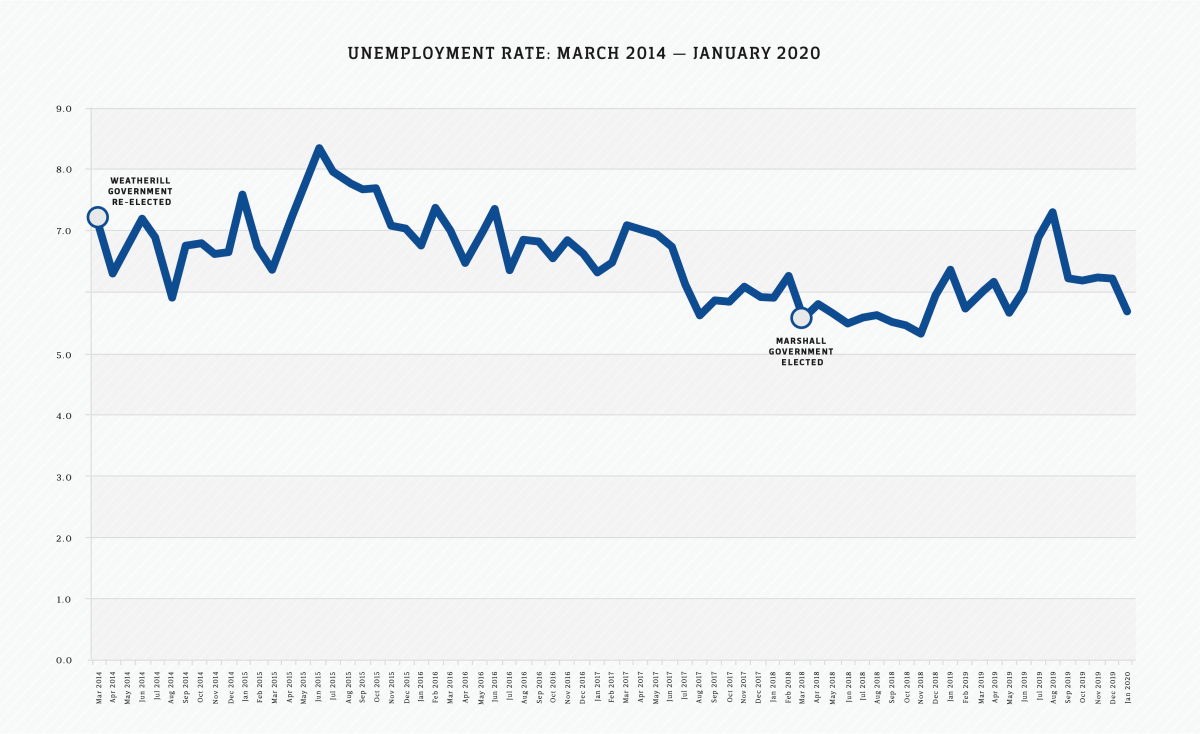

Data: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Graph: Nicky Capurso / Bension Siebert

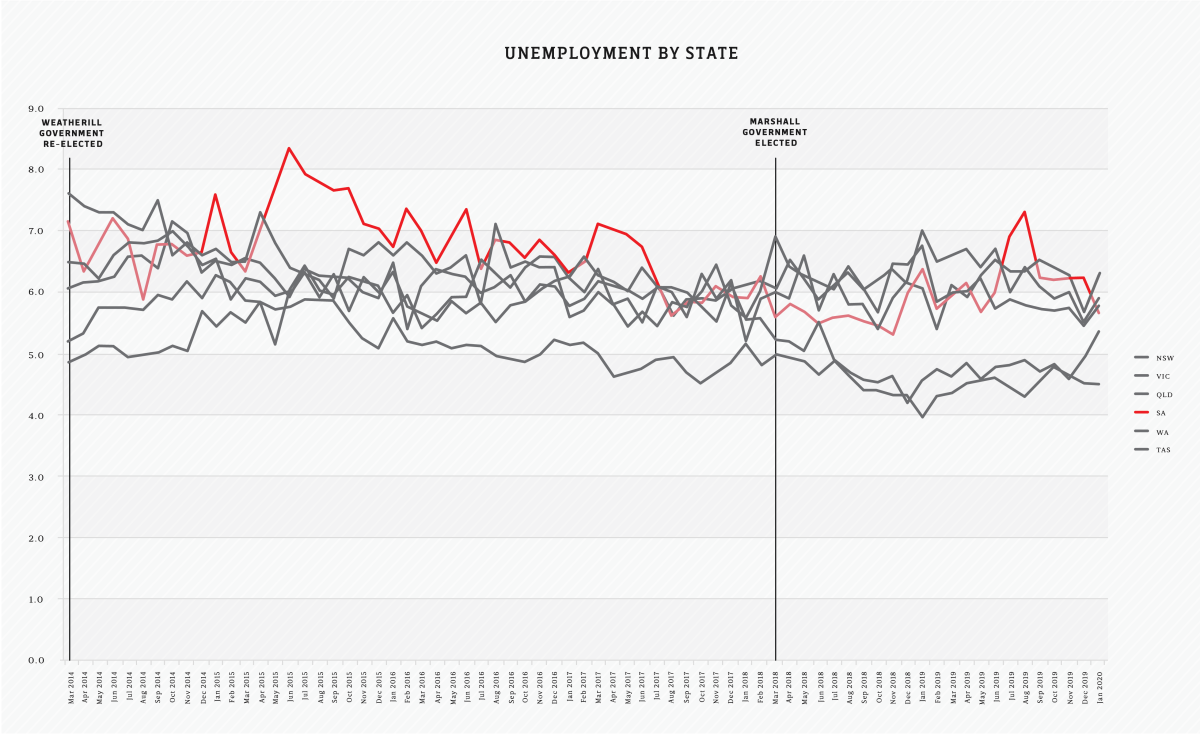

Firstly, unemployment was higher during Weatherill’s four-year term – 6.79 per cent on average – than it has been during the first two years of the Marshall Government: an average of 5.94 per cent.

It was also significantly higher – an average of 7.1 per cent – during Weatherill’s first two years than Marshall’s first two.

It also probably felt higher because much of the news coverage of the joblessness rate, including in InDaily, focused on whether or not South Australia had the highest unemployment rate in the country each month.

South Australia held the unwanted title over 27 months of Weatherill’s 48-month term, but only three months of Marshall’s 23 month term thus-far.

South Australia had the country’s highest unemployment rate 27 out of the last Labor Government’s 48 months in office – and three months during the Marshall Government’s 23-month term so far. Data: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Graph: Nicky Capurso / Bension Siebert

Mullighan conceded that the headline unemployment rate was higher during the last term of the Weatherill Government.

However, he argued the rate was heavily influenced by General Motors’ announcement in early 2014 that it would end Holden car manufacturing in Australia.

He said the Weatherill Government’s response to the crisis caused a turnaround in about 2016, after which the unemployment rate trended downward.

The jobless rate reached its lowest point in years in November 2018 – eight months after the election of the Marshall Government.

But it has been trending upwards since.

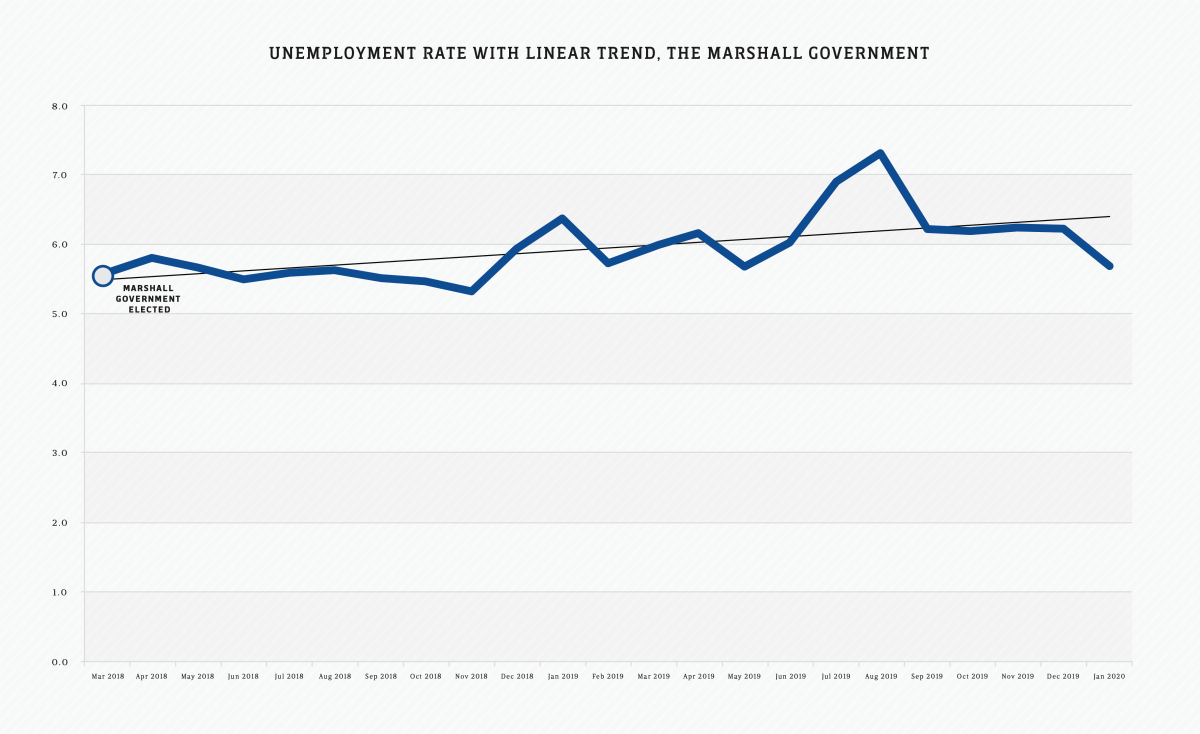

The graph below shows the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate, according to the ABS, since the election of the Marshall Government, with a linear trend-line.

Data: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Graph: Nicky Capurso / Bension Siebert

The trend unemployment rate – as opposed to the more turbulent seasonally adjusted rate – was lowest during the Marshall Government’s term in mid-2018, climbed higher until September last year, and has since started coming down again, with the latest figure marginally higher than it was when the Liberal Party won the election.

O’Neil said stagnating wages have led to a major reduction in retail spending across the country, contributing to higher-than-otherwise unemployment in South Australia.

Lucas said the SA unemployment rate remained higher than he would have hoped, which he described as a “natural corollary of the economic growth not being as strong”.

But Lucas pointed to South Australian defence and shipbuilding jobs, due to be created over the next few years, as cause for optimism moving forward.

The head of the French company, Naval Group, building Australia’s 12 Future Submarines Jean-Michel Billig addressed a Senate hearing last week, recommitting the company “to a level of Australian industry capability that will have the effect of at least 60 per cent of the Naval Group contract value spent in Australia”.

But it’s far from the 90 per cent figure spruiked by the company when it was pitching to the Federal Government’s competitive evaluation process in 2015.

It remains unclear what proportion of those jobs will go to South Australians.