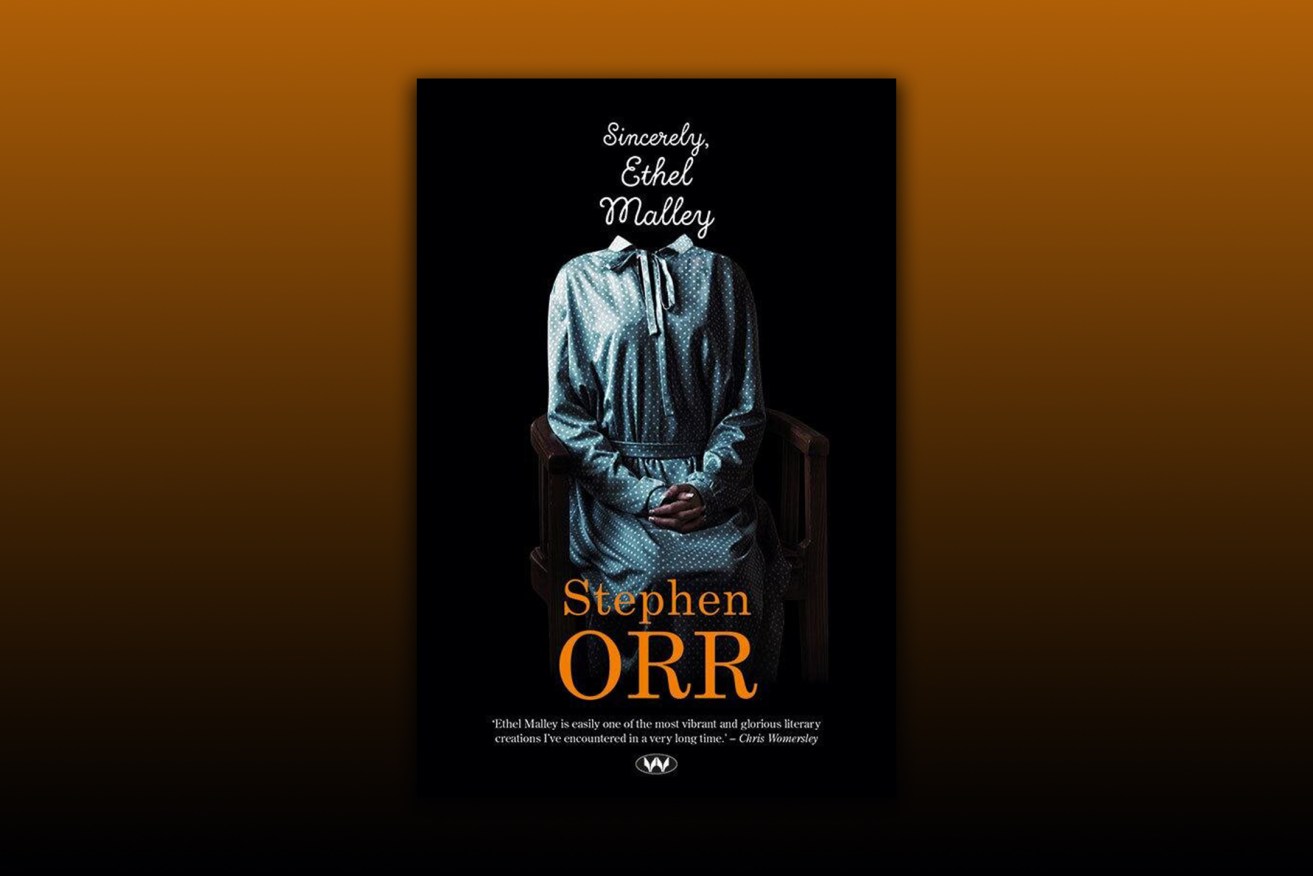

Book extract: Sincerely, Ethel Malley

In his imaginative and wryly witty new novel, Sincerely, Ethel Malley, Adelaide author Stephen Orr reimagines Australia’s greatest literary hoax, the Ern Malley Affair.

In 1944, conservative Sydney poets James McCauley and Harold Stewart infamously invented a series of deliberately obscure “modernist” poems in an afternoon, taking random phrases from sources as disparate as a dictionary and a medical textbook. Next, they invented soldier poet Ern Malley, recently deceased, as their author, and his sister Ethel as their emissary. Then they sent the poems to modernist magazine editor Max Harris in Adelaide.

Harris hailed them as genius and published them in a devoted issue of his magazine, Angry Penguins, only to be humiliated when the hoax was revealed.

In his novel, published this month by Wakefield Press, Stephen Orr playfully poses the question: What if Ern and Ethel were real? And what difference would that make to the value of the poems, which Max maintained his faith in to the end of his life?

In this extract from the novel, Ethel Malley brings Max Harris to visit the suburban home where her brother Ern grew up, and lived with her until his death, from Graves’ Disease, shortly before she found his poems and sent them to Max.

————-

The taxi dropped us, and we stood in front of number forty. ‘Well, here she is.’

I don’t know what he was thinking. Plain, ordinary, not a place you’d associate with one of – no, with Australia’s greatest poet. But that was the point: greatness came from shoe boxes, laddered stockings, coal mines, a little fruit shop on Parramatta Road. ‘This is where we grew up.’

Max lit a cigarette, stopped to take it in and said, ‘Not what I expected.’

Through our little picket gate (‘Dad put that in when we were about four or five’), past an orange tree (‘Ern’d climb it, but he’d always rip his clothes on the thorns and then Mrs Royal’d be on at him – make him sit there, half the night, with a needle and thread, fixing it’) and onto the porch. ‘I’m so glad we came, Max.’

‘It’s very middle-class.’

‘Nothing posh about us, Max. No St Peter’s College.’

‘We weren’t posh. That was a scholarship. If we hada had this …’ As he studied the neighbours’ yards.

‘Now, if you wouldn’t mind, Max, I try to avoid smoking in the house. Ern did, of course, but he wouldn’t be told.’

My brother, sitting a few yards away in a canvas chair, looking at us. Who the hell’s this, Eth?

I could’ve told him. The man who’s published your poems, Ern. But even then he mightn’ta been impressed, mighta said something like, Bit full of himself, isn’t he?

No, Ern, he’s the nicest man.

What, you fancy him, Eth? Grinning.

But the chair was empty, and had been for some time. Since he’d got so bad he couldn’t come out of his room. ‘He enjoyed sitting there,’ I said to Max. ‘Said he liked to listen to the birds. But I’d often look out and see him talking to someone going past. I think that’s what he was after … company. There’s only so much you can say to one person, isn’t there, Max?’

He just flicked his cigarette into the garden.

Entering, bags left in the hall, and I said, ‘And here, to your left, the sunroom, where he’d go of a morning, and here, the lounge … come on, then.’

We went in, and he stood, astonished. ‘Like it’s set for a play.’

‘Which one?’

But he wouldn’t say. Just turned circles, taking it all in. He sat on the lounge, and sunk into it. I must admit, it was just as bad as the one at Wilson’s. But he didn’t say anything. I approached the Bösendorfer, opened the lid and said, ‘This is it, Max. Hours and hours.’ I sat, played a few bars, sang a few lines. ‘They were good times, at the beginning … Somebody’s pinch’d his wings and toes, I had a bit of parson’s nose … Any requests?’

‘Nothing comes to mind.’

‘It’s a long way to Tipperary …’ Pounding the notes, although now I was Ern, hands criss-crossing, turning to Dad and taking the octave: ‘… it’s a long way to go …’ Ern, in his old recliner, lit a fag and looked at Max like, he fancies himself a bit, doesn’t he, Eth?

You be quiet. Always thinking the worst of people.

Max said, ‘Considering she washed up on a beach, she’s in good nick.’

‘Dad put a lot of work into her.’

And Ern, protesting, because he had to help sand the wood, help with the varnishing.

‘It paints a picture,’ Max said, examining the old candelabra (not a fancy one), the mantle clock that hadn’t worked for years, the hole in the rug near the front window where the dog had tried to dig a hole. I wanted to tell him about that, too, but supposed there was a limit to his interest. Wanted to say how Ern had told her, You can’t take her, Mrs Royal, she’s a good guard dog. Wouldn’t let no one get in.

She’s also a good shitter. Give her here.

I’m not givin’ her up.

You’ll do as you’re told.

Out the door, the car, the RSPCA. Me and Ern sitting, watching, studying the hole in the carpet. As she sat in the front with our dog in her arms (so happy to be going on an outing). Terry driving, as always, as commanded. Ern saying, I hate her! I hope she dies soon, today. I won’t help her, Eth. Before running out to try and reclaim his dog.

No, don’t think what you’re thinking. There was no way I could’ve helped Mrs Royal. It was quick and clean. God took her, in the same way she took the dog. See, it makes sense. God is dog backwards. What you do to one gets done to you. Amen.

‘He could play all of these,’ I said to Max, showing him the pile of manuscripts. ‘Self-taught. Like I said, no money for lessons. He was possibly a genius.’

‘That’s crossed my mind.’

‘If they hadn’ta called him up … Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square …’

He still didn’t join in. Just like on the train from Adelaide. A group of six or seven soldiers singing, and me, ‘It’s a long, long way to Tipperary but my heart’s …’

This was – is – the funny thing about Max Harris. Dispassionate, you might say. Just at those moments when you might expect a person to open up, let his or her defences down, become the inner Ern – just at those moments, he’ll back off, close up, give little or nothing away. Not sure why. Like if he was happy, for a moment, something terrible might happen.

The soldiers sang it over and over, me joining in, one of them saying, ‘You got a good voice on you, missus.’

‘It was my brother’s favourite. He always sang it. Played on the goanna.’ Another round, and then: ‘He was in the AIF as well.’

‘Yeah? What battalion?’

‘Second Third.’

‘Don’t say. We were fighting with them. What was his name?’

‘Well …’ I wasn’t sure I wanted to discuss it; not here, not now. I didn’t want to ruin a nice evening. Or afternoon. But Max said, ‘Ern Malley.’

The first soldier turned to the others and said, ‘Malley … doesn’t ring a bell.’

Things settled, and as we tackled the Blue Mountains, Max said to me, ‘You’d think someone mighta remembered him?’

‘Lotta people in a battalion, Max.’

‘But someone like Ern?’

‘What?’

‘Just sayin’. You woulda thought someone …’

Back at number forty, in the lounge, I said, ‘How about a cuppa?’

After I put on the kettle I showed him Ern’s sleep-out, and he said he’d prefer the lounge, and this suited me, as it’s hard, isn’t it, sleeping in a dead man’s bed? He stood staring at the stretcher, the imprint of a body, the old army sheets and rug (Mrs Royal, Legacy), the few knick-knacks I’d left, in memoriam.

‘This is where it all happened?’ Max said.

‘I guess so, although like I said, I never had any idea.’

‘He must have hid it well.’ Sitting on the stretcher, searching every corner of the room with his little brown eyes. ‘It’s hard to imagine how he could write all those poems and you didn’t … I mean, you’d think you mighta walked in on him once? Maybe he only worked at night – after you were asleep?’

‘Maybe.’ I crossed my arms. ‘Maybe I saw, but didn’t notice.’

‘How?’

‘Assumed he was writing a letter, although he wasn’t.’

He just stared at me. ‘Still, it’s good to see where he wrote. Although, it’s not that inspirational.’

‘No.’

‘He must’ve travelled, Ethel.’

‘How do you mean?’

‘Astrally. He must have risen from his bed, floated to Melbourne, Innsbruck, all over the place. He must have had a good imagination.’

‘I guess that’s how all writers work.’

‘I reckon you’re right.’ Still looking around, trying to work out Ern Malley. Ern on his bed, saying, Piss him off, Ethel. Man’s room’s a private place.

He’s just interested, Ern.

Piss him off!

Max checked under the bed, but there was nothing; on the shelves, nothing, except the old soccer ball. And he said, ‘Farsa? What’s that mean, Ethel?’

‘Couldn’t tell you.’

So he took out his notebook (as he always did at such moments) and wrote it down. I said, ‘Ern found it on the beach when him and Dad were collecting. He reckoned it’d come all the way from Chile.’

‘Don’t say?’

‘And one day, he reckoned, he was going to find the owner, return it.’

‘But he never did?’

‘No.’

‘That’s how it works, eh, Ethel? Mean to do something, but time gets away from you?’

‘That’s the kettle boiling,’ I said, and went out and switched it off, realised he hadn’t joined me, returned and found him searching the bottom of the wardrobe.

Shit. The envelope! He’d removed the rubber band, and the photos, and sat studying them. I took a few steps closer and saw the various shots: the boy, only a toddler, playing on his front lawn; five or six, on a jungle gym; in a park (the photo had been taken from a distance, and it was blurred, but you could tell it was the same boy); as a nine-year-old, leaving his school, turning to look at me, as if, somehow, he knew who I was; a year or so older, playing in the ruck (another bad photo, the shot obscured from where I was hiding the camera); and several of the same boy mowing the lawn for his dad, pruning, for his mum. Max said, ‘Who’s this?’

I reclaimed each of the photos I’d hidden (I wasn’t expecting company). ‘A friend’s son.’

‘Right.’ But, of course, his suspicions right.

‘You ready for a cuppa?’

‘Coming.’

A few minutes later we were sitting around the dining table, if you could call it that. You could squeeze six people around it, arm to arm. Old, wobbly, scratched from a thousand plates, burnt by hot mugs, plates of suet. ‘This place is full of memories,’ I said. ‘I’ve been wondering if I should sell it. Find something smaller, with less garden.’

‘You can’t,’ Max said. ‘Your whole life’s here.’

‘That’s the problem. Every day you’ve got to look at it.’

He waited; wanted the details, I guess, although I wasn’t sure he deserved them.

‘It’s upsetting, Max.’ I felt like crying. ‘Like he might walk through that door at any moment. Say hello, ask what’s for dinner. If I had one of those new places, with the double-brick, I could get on with … but you’re right …’ Sighed. Because that’d be like burying what was left of Ern. Some family moving in with their kids writing all over the walls; some wogs, cooking tomatoes all day, the place smelling of garlic. No, I couldn’t do it.

‘It’s early days,’ Max said. ‘Course the place is full of memories, but they’ll fade.’

‘Not sure I want them to, Max.’

‘Well, you choose how you remember. Could become a shrine to Ern – if the journal sells, if people take to him. A line out the door. The Ern Malley Memorial House, seven and six a ticket. Yes, folks, this is where the great man slept … stand back there, son, don’t touch his bed.’

Max could always get around you. I smiled, reached across, touched his hand. ‘D’you reckon?’

‘Of course. Like Lawson’s house. People visit that.’

I squeezed it. ‘You know how to cheer a person up.’

‘No point getting gloomy, Ethel. I can feel Ern here, beside me, talking to me. How are you, Ern? Good thanks, Max. Nice job you did on me poems. No worries, Ern, any time. People seem to like them. Some, that is. Well, Mr Harris, you tell them others to take a long walk off a short jetty.’ He smiled, sipped, squeezed, but then reclaimed his hand. Pity.

‘Memories, everywhere,’ I said. ‘Dad, standing on this very table with a bottle of beer in one hand and a pile of bills in the other, saying, No way out, Ethel. Stumbling, then he was on the ground. Just about broke a bone.’ As I noticed where he’d fallen. ‘But he got himself up. Cut lip, black eye. Cleaned himself off (me and Ern, shoving him in the shower). Then we made him a coffee and he sat here drinking it, reading the paper, and he said, Christ, listen to this: the Esso Reliability Trial … See, that’s how it works, Max. When God closes one door …’

He didn’t seem convinced.

‘Then he was off, fixing up his Indian.’

Max drained his tea, said to me, ‘What about your grandparents?’

‘Both sets in Liverpool. We never saw them. They never came to visit. Which seems strange, doesn’t it, Max?’

‘Why?’

‘Knowing they had grandkids in Australia.’

‘Maybe there was no money?’

‘Maybe.’

‘In which case, they’d write, or phone, wouldn’t they?’

Enough of the past. ‘You’d like a shower, wouldn’t you, Max?’

‘Wouldn’t say no.’

So I set him up in the lounge room beside the Bösendorfer, made up his bed while he was in the shower. Returned to Ern’s room, stripped the sheets and rug, because they’d do, and sat on the stretcher and said, ‘You’re gonna have to make more of an effort, Ern.’

————-

From Sincerely, Ethel Malley, by Stephen Orr, published by Wakefield Press. Extract republished with permission of the author and publisher.

From Sincerely, Ethel Malley, by Stephen Orr, published by Wakefield Press. Extract republished with permission of the author and publisher.

Stephen Orr is the author of eight novels (including the Miles Franklin longlisted Time’s Long Ruin and The Hands), a volume of short stories (Datsunland) and two books of non- fiction (The Cruel City and The Fierce Country).