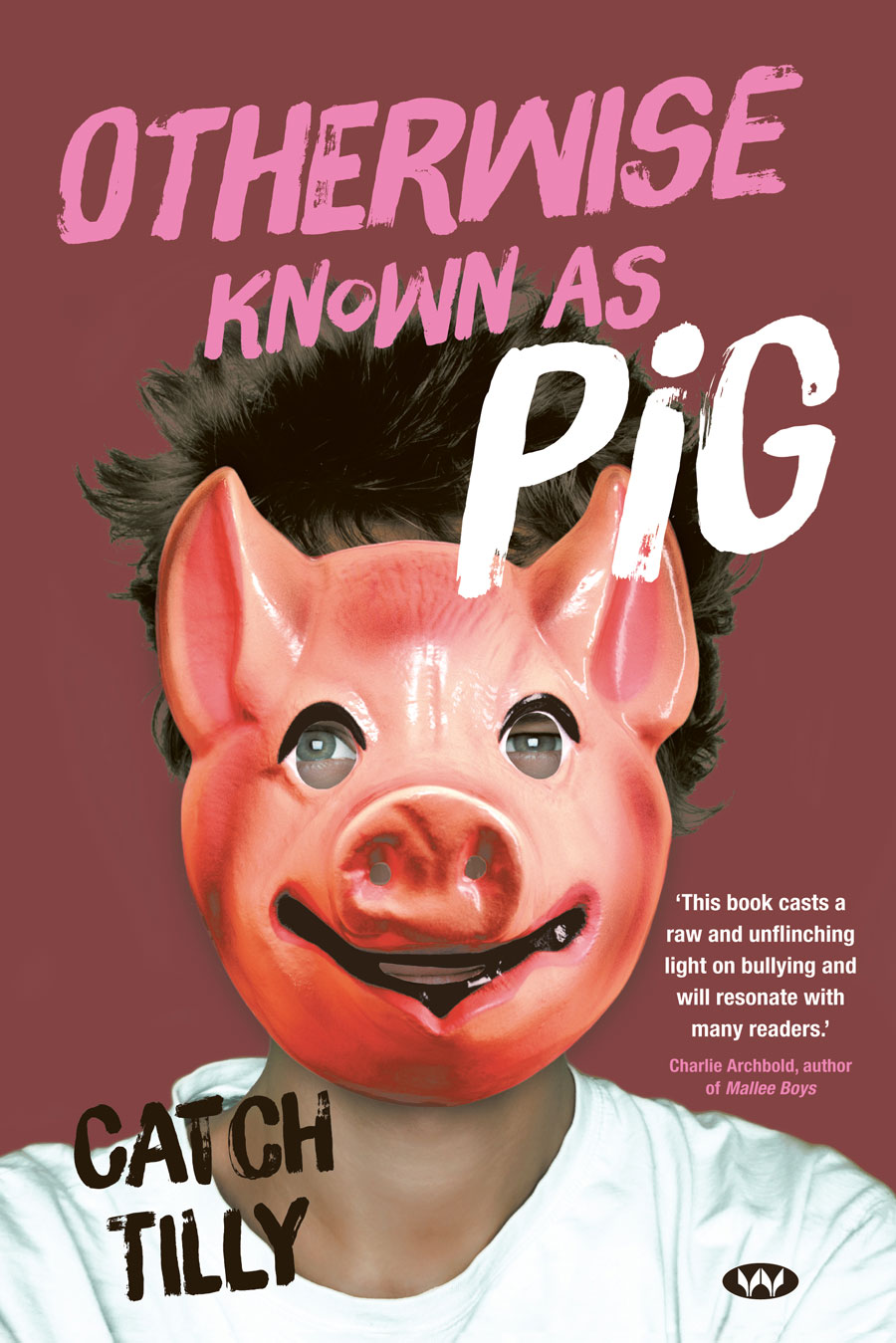

Otherwise Known as Pig shines a light on bullying

BOOK EXTRACT: Adelaide writer Catch Tilly’s new young adult novel, Otherwise Known as Pig, follows years spent researching schoolyard bullying – a problem she says is so prevalent it needs its own #metoo movement.

Tilly, a former high school teacher, originally wrote a play about bullying and was motivated to turn it into a novel after students told her how realistic and empowering they found it.

Otherwise Known as Pig, published this month by Wakefield Press, is set in a dysfunctional high school and narrated by a smart-mouthed student, Morgan (aka Pig), who is regularly beaten up by a classmate known as Stormin.

Tilly, who believes toxic masculinity creates cycles of bullying, says both Morgan and Stormin are trapped by their image of what a man should be.

Tilly, who believes toxic masculinity creates cycles of bullying, says both Morgan and Stormin are trapped by their image of what a man should be.

Numerous people shared their memories of childhood bullying experiences with her while she was writing the book.

“People just tell you stories. It’s like #metoo. Once you start to look, it’s everywhere.

“There should be a #metoo movement for bullying, to bring it into the open.”

Tilly hopes her book will encourage readers to say something next time they see someone being bullied: “Because that’s what we need to do. And it’s hard.”

The following extract is the first chapter of Otherwise Known as Pig.

_________________________

Stormin punched me in the mouth today.

It’s always a shock: that sudden explosion of pain and the short involuntary cry as my lips meet my teeth. I hate that cry. That’s when he laughs. Along with the rest of Year 9. Maybe they’re too scared to do anything else or maybe it’s funny – watching someone else get hurt.

They’re laughing now. Some are even applauding and calling out suggestions. It’s like a football match. Except that I can’t play sport and Stormin doesn’t like suggestions. He’s just standing there: over six feet tall, with his fists re-clenching on the end of gorilla arms.

‘Come on, Stormin, hit him.’

Smack. It’s a single punch and Alex, the kid who’s spoken, is down. Stormin’s clearly pissed and what I should do is keep my already bloodied mouth shut and just back off like everyone else.

‘What’s wrong, Stormin? Don’t you like team games?’ I say instead.

‘Nah, I don’t.’ Then he hits me again. It’s a different shock this time because he gut punches me and I lose breath in a sickening thud before his fist connects with my eye and stars explode. It’s about now he starts to smile. At about the third or fourth punch, when I’m down and cringing and wishing I could take his stupid face apart and knowing I can’t. I hate that smile.

‘Still a loser, Pig,’ he says. ‘Guess you haven’t learnt much over summer.’

‘I don’t know,’ I reply, bloody, bowed and hating his guts. ‘I can read.’

Which is when he kicks me. I really should learn to keep my stupid mouth shut. Seeing Stormin thoroughly occupied, the rest of Year 9 drift back, although they do wait till he’s left before resuming their commentary.

‘Loser.’

‘Coward.’

‘Hopeless.’

‘Pussy.’

‘Pig.’

That’s me: Morgan Patrick Lohdi – otherwise known as Pig.

I spend the rest of the day in sick bay. At least I’m missing the usual first day activities: How to Be Bored to Tears in Assembly, Get a Good Head Start on This Year’s Vandalism, or Your School’s Drugs and How to Get Them. It must be a great day – provided you don’t have a brain.

Sick bay’s crowded – as usual. I can hear a Year 11 kid who is coming down from something while our overworked nurse, Miss Sefton, hands out gauze pads to several Year 8 basketball victims.

‘Hi,’ I say, slumping in a chair. ‘If you’re giving them away, I’ll take six.’

Which would have sounded cool if I hadn’t been shaking when I said it. I can see the three Year 8 girls edging away.

‘Don’t worry,’ I tell them. ‘It gets worse.’

A throat-tearing scream from next door makes them all jump.

‘What’s that?’ one of them asks as Miss Sefton rushes off.

‘Exorcism,’ I explain nonchalantly. ‘Quite common in the upper years. I mean,’ I add, as they look doubtful, ‘does that sound like anything human?’

It doesn’t, and I can see my theory gaining weight. We’ve just got up to the superhuman strength of your average demon and how they haunt the school when Miss Sefton comes back in.

‘Oh, do be quiet, Morgan. There’s nothing supernatural about a bad drug experience.’

‘Are you certain it’s drugs?’ I say, but the mention of my name has already sidetracked the conversation.

‘Are you Morgan?’ Girl One asks and I can hear her whispering – loudly – to her friend. ‘My sister told me about him. She said to stay away from him.’

Girl Two takes a surreptitious look at me. ‘He’s sort of cute,’ she says (an opinion she’s bound to change). ‘Is he Asian? Can he do martial arts?’

Girl Three shakes her head and curls a heavily lipsticked mouth. ‘He’s not a Chink,’ she answers, not bothering to keep her voice down. ‘The eyes are wrong. And my brother says he can’t fight for shit.’

‘Worst loser in the school,’ Girl One confirms. ‘That’s what my sister said.’

It’s the price of fame. Girl Three has lost interest and is putting on even more lipstick – I think she’s after a world record – but Girl Two is of a more scientific turn of mind.

‘Is he tribal?’ she asks, looking at the two-shades-darker-than-suntanned skin that means I have to dodge cops as well as Stormin. ‘Is that how your sister knows him?’

Girl One, who is dark-skinned and pretty and clearly Indigenous, shakes her head. ‘He’s not family,’ she says.

‘Then he’s a terrorist?’ Girl Two’s look of excited fear is the most respect I’m likely to get all year. ‘Is he going to blow us all up?’

Girl Three leaves her lipstick record to laugh. ‘Him?’ she says. ‘He couldn’t do anything.’

‘Total loser,’ Girl One agrees. She turns her back and takes the tube of lipstick off her friend. ‘And you call him Pig.’

Girl Two giggles.

Well, there went the last of my guilt over the exorcism story. Only wish I’d managed to terrify her more before my identity was revealed.

Odd how someone always thinks I’m Aboriginal. Not the actual Indigenous kids, of course, but someone. And when they exhaust that option it’s always, am I a terrorist? I guess being three-quarters white and one-quarter not has left me looking like nothing in particular. It’s pretty unimportant compared with my inability to kick a football.

That’s what’s left me looking like shit.

‘Spoilsport,’ I mutter as the girls leave and Miss Sefton starts cleaning blood off my face.

‘You shouldn’t tease them, Morgan.’

‘Why not? First day back is the only chance anyone will listen to me.’

She doesn’t answer, just keeps checking me over. Icepack for my face, cream for my ribs – she knows the routine as well as I do. She’s a nice lady.

After a minute I mumble, ‘Sorry.’

That’s all right. It can’t be easy for you.’

Well, she’s right about that. It’s not an easy life, being a loser.

‘Do you want to report this?’

‘We already tried that,’ I say. ‘No point.’

It was last year, term two, just after Stormin had iced both me and Alex. Miss Sefton had helped me prepare the report on my injuries but then six other witnesses, including Melissa Hancock – a girl I’d thought was my friend – swore that I’d been fighting. End result: warning for Alex, three-day suspension for yours truly and a lot of pain from Stormin when I got back to school. Conclusion had been that Stormin couldn’t have been involved; he didn’t have a mark on him. I’ve always wondered whether they really believed it or just didn’t want to tangle with Stormin.

She doesn’t repeat the suggestion, just hands over another icepack and gets me a Coke from the machine. You know you’ve hit rock bottom when your only friend at school is the nurse.

She gave me this journal to take home. I think it’s supposed to be therapy. Or maybe proof for later charges? But at least it’s someone to talk to who doesn’t call me Pig.

Why ‘Pig’? Everyone has called me Pig since Stormin labelled me in Year 4 and I still don’t get it. I’m not fat, I’m not pink and my eyes don’t bulge out. I DON’T LOOK LIKE A PIG!

‘What’re you writing?’

My older sister Cynthia looks like a pig.

‘What is it?’ She pushes her way into the room I share with my brother. ‘You can’t have work to do yet. We never do anything on the first day back.’

‘I noticed that, wish I hadn’t gone.’ I turn back to my book. ‘It’s not work, it’s just stuff I’m writing.’

‘What?’

‘Stuff.’ There is no way I’m telling my sister I’m writing a journal.

‘It’s ’cause no one will talk to you.’ She may be right. ‘It’s pretty pathetic when the only person who’ll talk to my brother is a piece of paper.’

‘At least it’s an intelligent reply.’

‘Yeah?’

‘But I wouldn’t expect someone who still demands a gold star for getting her name right to understand.’

‘Just stay away from me, loser.’

‘With pleasure. I do have some standards.’

She’s looking around for something to throw at me when Mum walks in. ‘There you are, Cynthia love. So nice to see you getting on with your brother.’

Cynthia and I just look at her. Cynthia looks like Mum, blue-eyed and blonde, and I’m dark-haired and dark-eyed like Dad, but I bet we look the same in our blank incredulity.

‘Dinner in half an hour, loves. Roast chicken with all the trimmings.’

‘Thanks, Mum,’ we chorus, but the door has barely closed before Cynthia is adding, ‘and remember, don’t let anyone know we’re related, or I’ll make you regret it.’

‘Stand in line,’ I say, ‘I’m not your exclusive punching bag. Besides,’ I add as she picks up a convenient missile, ‘I have no problems at all disassociating myself from a sister of such mind-numbing stupidity.’

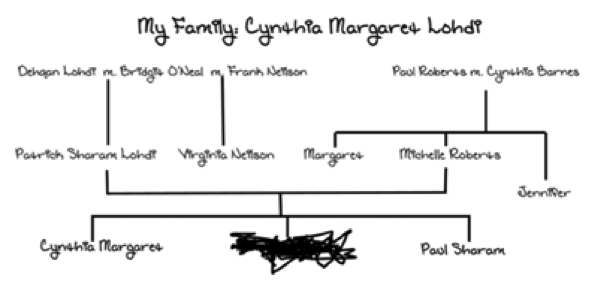

Which is perfectly true and anyway Cynthia never admits we’re related. I’ve still got a copy of the family tree she had to do in Year 6.

That’s me: the blot in the middle. God, my ribs hurt.