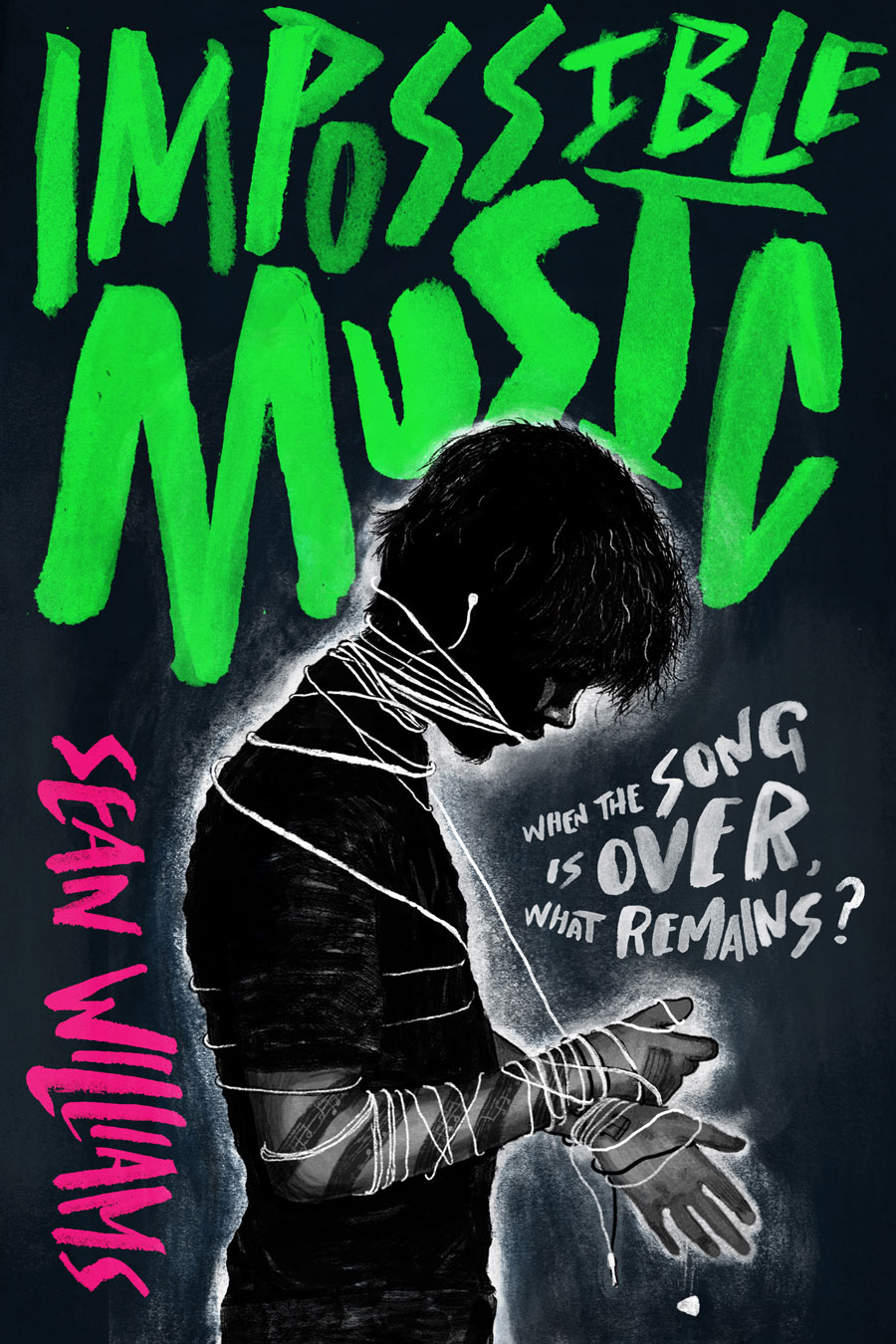

Book extract: Impossible Music

Adelaide author Sean Williams’ new novel, Impossible Music, explores deafness from the perspective of a guitarist who suddenly loses his hearing. It springs from Williams’ love of music and a fear of losing the thing he most loves: writing.

Sean Williams has written more than 40 novels and 100 stories, but Impossible Music is his first novel set in Adelaide and is a departure from his usual fantasy/speculative fiction.

The book is narrated by a 17-year-old promising heavy metal guitarist named Simon.

“When a stroke suddenly robs him of the ability to hear, he feels as though he has lost everything,” Williams tells InDaily. “It takes several attempts to get his life back together before he realises that he’s not the only one struggling.

“Impossible Music began 15 years ago as a near-future thriller, very much in my usual style. The more I researched hearing loss and deaf culture, however, the less interesting spectacle seemed to me and the more inspiration I found in the real world.

“Chronic pain, which made my life miserable for several years, was a key ingredient in the mix: I am not deaf, but I do know how it feels when the very thing that defines you is slipping away.

“Simon’s quest to invent an entirely new form of music, one that can be appreciated equally by hearing and deaf alike, so he doesn’t have to miss out, may seem as mad to us as it does to his family and friends, but it comes from a dark place we may all visit at some point in our lives.

“I sincerely hope that this book will inspire anyone on their own journey.”

The following is an extract from Impossible Music, which is published by Allen & Unwin and available now.

———

Three weeks after my stroke, I attended my first Deaf Class, but with a sense of obligation instead of the this is a new beginning, yay! that my counsellor would rather I embraced. I was sick of the facsimile of hearing. I wanted the real thing, and no one could give it to me.

Because none of us had planned to be there – who would? – we each had a different way of reacting. The guy with the thick handlebar moustache, a forklift operator whose years working in a factory had finally done in his hearing, watched everything closely and reproduced the signs with mechanical precision belying the look of his leathery, knuckled hands. The woman with bouffant, dyed fake-natural hair came bearing voluminous notes and a repertoire of apologetic expressions ready for when she got things wrong; she had lost her hearing from a bad case of the flu, of all things. The guy in his twenties who hit on me once seemed almost excited to learn this new skill, engaging with an exuberance that was desperate at times. Or maybe that was just me projecting. He was a recreational diver who timed an ascent wrong and blew his ears out.

Deaf Class was where I met G. Our teacher was a cheerful Deaf woman in her fifties who, via a mixture of handouts, projections, and whiteboard scribbles, did her best to bring us up to speed. Her name was Hannah, and I would’ve liked her more had our circumstances been different. The first thing she taught us was the difference between gestures and signing.

Deaf Class was where I met G. Our teacher was a cheerful Deaf woman in her fifties who, via a mixture of handouts, projections, and whiteboard scribbles, did her best to bring us up to speed. Her name was Hannah, and I would’ve liked her more had our circumstances been different. The first thing she taught us was the difference between gestures and signing.

Gesture is any form of nonverbal communication, like shrugging, giving someone the middle finger, or blowing a kiss. Those early days, my home life was conducted almost entirely through gestures, every exchange an elaborate, torturous variation on ‘pass the salt’. Deaf and hearing alike use gestures. They’re not the same as signing, though, which is a full-on language, with rules.

G was a master at expressing disdain by means of gestures as well as posture (slouching, mainly), proxemics (where she stood in relation to others, usually apart), hand position (biting her fingernails so neither her fingers nor her expression was clear), and so on.

At first it was intimidating, particularly if she and I were paired together. Later, I found it amusing. Perhaps because it was clear I wasn’t enjoying classes either, she seemed to settle on me as the least irritating person available

People are building sign-language gloves, you know, she texted me once from the other side of the room during a ten-minute break in class. Like dictation software but for Deaf people. The machine turns the signs into words on a screen so ordinary people can read them.

How does that help us? We can’t sign.

Ah, you see, that’s the best bit. We don’t need to. We can still talk, right? Ordinary dictation software can transcribe it, so Deaf people can read what we’re saying. Then the gloves transcribe what they’re saying back to us. No need for us to learn sign language at all!

Could work. It’d all have to be done through computers, though. Or phones.

That’s where augmented reality comes in.

Now I know you’re messing with me.

Someone has to. I mean, have you looked in the mirror lately?

That stung a little, because I wasn’t sure how she meant it. Was she saying I was sloppy-looking? My hair is long and straight and not easy to keep in condition. I have a goat patch on my chin, but nothing as protuberant as Tutankhamun or the bassist from System of a Down. The rest I keep clean-shaven.

Or was she talking about my clothes? I’m a jeans-and-band-T-shirt kind of guy, with Converses or something chunkier if I’m in a particularly metal mood. The money I don’t spend on my guitar goes on my feet, mainly.

So to be dissed, potentially, by this hot stranger, possibly the last one who’d ever try to talk to me in my isolated new world . . . well, I wanted to know exactly what for.

I asked her, in response to her mirror crack, Have you ever listened to a recording of yourself talking?

Not lately. Duh.

Of course not. Before.

Who hasn’t?

It sounds weird because we’re used to hearing our voices via the bones of our skull and jaw. That’s why we sound so bassy and warm, to ourselves. We all have this overinflated sense of how good we sound, because we never hear ourselves right.

Is that true? Huh. Interesting. But who says the way other people hear us is the ‘right’ way to hear us?

My point exactly. Mirrors are the voice recorders of the eyes.

Wait. Wouldn’t they be the echoes of the eyes? Or wouldn’t seeing yourself in a video be the same as a voice recording?

Are you always this pedantic?

Only when someone says something wrong, but still interesting.

I’ll take that as a compliment.

That was the first time she smiled at me, and I felt something flutter through me. It didn’t feel like passion, but it certainly felt real.

———

Read more about Impossible Music here and see a list of Sean Williams’ other published works on his official website.