The time I taught Willie Nelson to play the didge

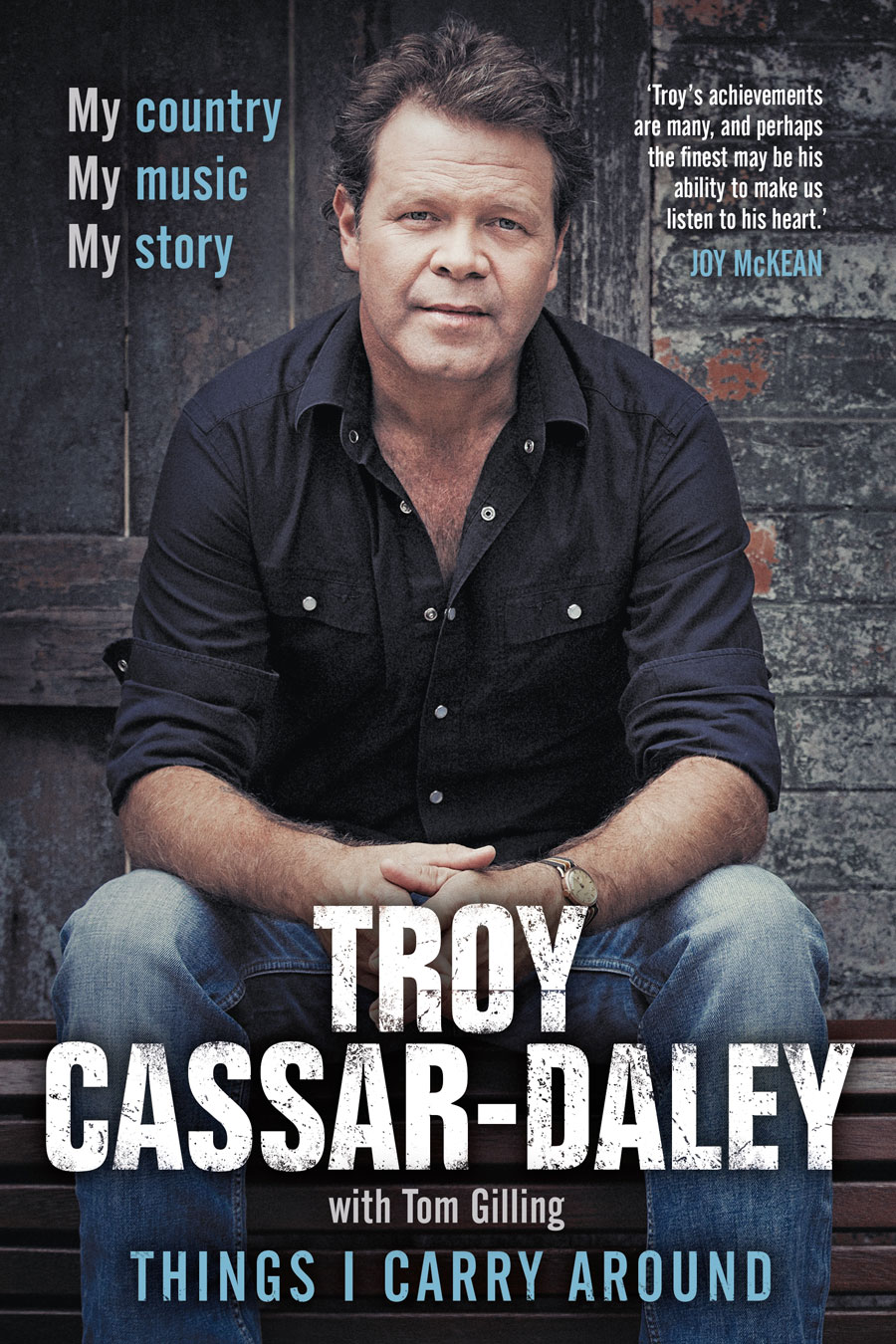

Teaching Willie Nelson how to play the didgeridoo and getting caught up in a haze of his “blue smoke” is one of the stories Australian country singer Troy Cassar-Daley shares in his autobiography, Things I Carry Around.

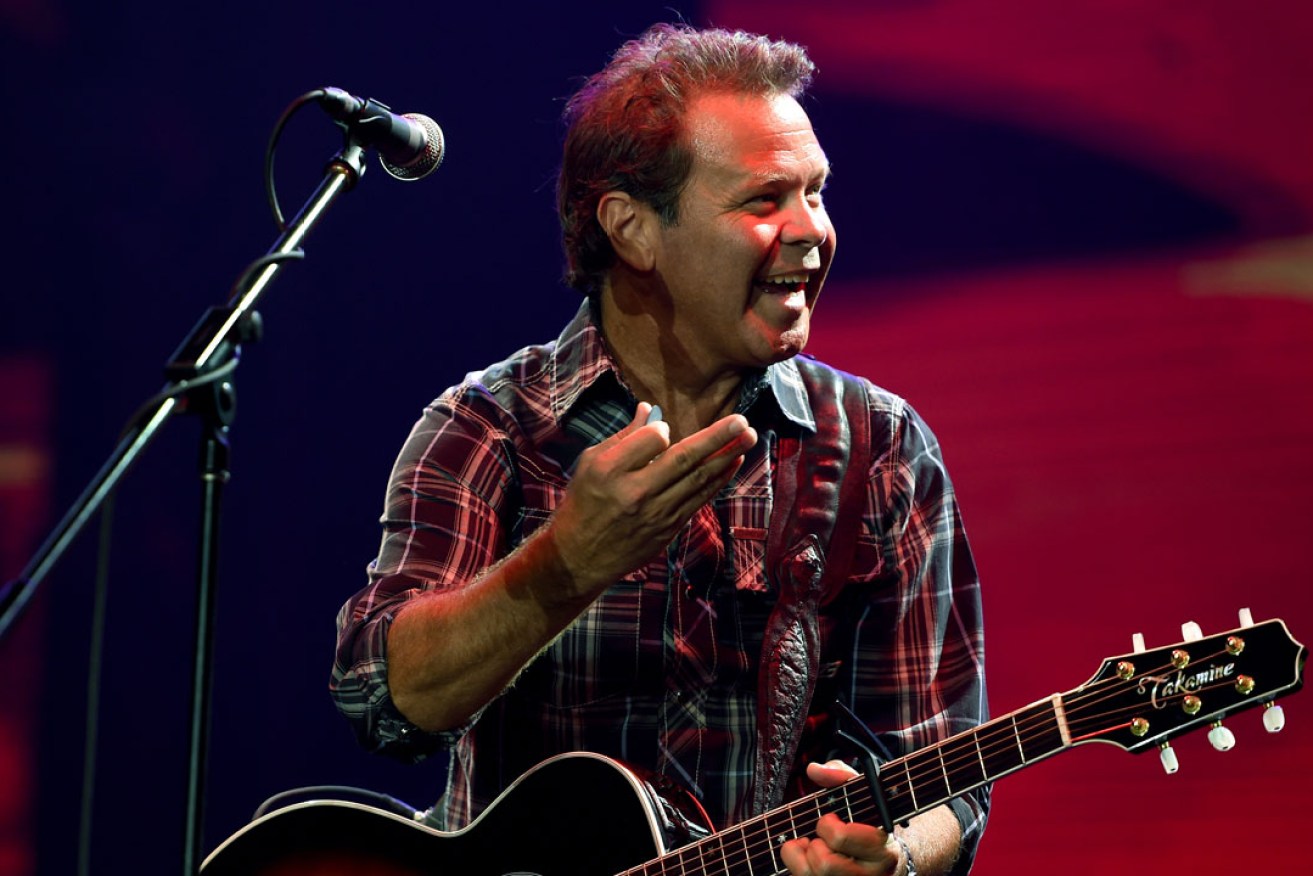

Troy Cassar-Daley, pictured at this year's Tamworth Country Music Festival, will launch his new book and album in Adelaide this week. Photo: AAP

Cassar-Daley will perform his first South Australian show in around three years – at Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute on Thursday – to launch both the book and his tenth studio album.

In Things I Carry Around, written with Tom Gilling, the multiple Golden Guitar and ARIA award winner writes about early life in his extended indigenous family, performing at Tamworth for the first time, and playing with musicians such as Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Slim Dusty and Merle Haggard.

The following edited extract recounts his colourful experiences with Cash and Nelson while on tour with the country music super-group The Highwaymen, whose members also included Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson.

***

I was at Allan and Barb’s house in Harbord when the phone rang. It was Gill Robert, who had come up with Gina Mendello to watch me play in Tamworth before Sony offered me the record deal.

Gill sounded pretty pleased with himself. He said, ‘Mate, we’ve organised to get you on as the support for The Highwaymen when they tour Australia in November.’

I was so gobsmacked that I almost swallowed the phone.

The Highwaymen were not just any old group: all four members – Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson – were legends of American country music. When I was a kid, I loved all these blokes’ music and bought a lot of their records. I’ve been a fan ever since.

The Highwaymen were Sony artists and so was I. Someone in Australia had pulled a few strings and that’s how I got the gig. All the same, I couldn’t believe it. Me on the same bill as Johnny, Waylon, Kris and Willie … ‘Pinch me, mate,’ I wanted to say, ‘I must be dreaming.’

When the tour was announced, the plan was for The Highwaymen to play five shows, but those dates sold out so fast that another five were added. That meant I would be playing ten shows with four of the legends of country music.

I was packing death about the prospect of standing up there in front of an audience that had paid to see The Highwaymen. It was bad enough when audiences had come to see Gina Jeffreys. But I knew I had a great band behind me: Stuie on guitar, James Gillard on bass, Shane Flew on drums and the brilliant Michel Rose on steel guitar.

It took us a couple of shows to get accustomed to the set- up – the catering, the big capital city entertainment centres, even the experience of seeing our idols eat dinner – but by the third night we were right into it. Even so, for a bloke who’d grown up listening to these legends on a record player at Halfway Creek, sitting a table away from Johnny Cash and June Carter took a bit of getting used to!

The big guy doing the introduction would walk onstage and say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, tonight, The Highwaymen,’ and the whole place would erupt. When the applause died down he’d say, ‘But first, please welcome ARIA award-winner and Sony recording artist Troy Cassar-Daley,’ and I knew everyone would be thinking, who the hell is Troy Cassar-Daley? Talk about a let-down for the audience!

You can’t big-note yourself in company like that; you have to remember who the audience has come to see. Despite the album and the ARIA, I was an unknown quantity to most people in those days.

By the fourth gig I’d plucked up the courage to get my Takamine guitar signed by all of The Highwaymen. First stop was the Man in Black, since his dressing room was next to mine. Johnny Cash was the oldest of the four and he had a few health issues during the tour. He didn’t socialise as much as the others but spent most of the time hanging with his wife, June. On that fourth night the tour manager and I knocked softly on the door, and this huge figure of a man with a distinguished head of silver hair slowly filled the doorway. In a gentle voice he asked, ‘How can I help you, gentlemen?’

I said, ‘Would you mind signing my guitar, Mr Cash?’ ‘Not at all,’ he said, ‘but let me play it first.’ Johnny strummed a couple of chords and sang a couple of lines from ‘Bird on a Wire’, then signed the guitar and handed it back to me.

I noticed that in his dressing room there was a beautiful black Martin acoustic leaning in the corner with a signature in white pen on it. I thought, whose signature would Johnny Cash have on his guitar? so I had to ask him.

Johnny glanced over his shoulder and said, ‘Son, Gene Autry signed that guitar for me’ and as I walked away I thought, wow, even Johnny Cash has heroes.

***

I had records by each of the four Highwaymen but the artist I had the most of was Willie Nelson. Willie is a really special soul and I saw countless examples of his generosity on that 1995 tour. He had time for everyone in our crew and would go outside after shows and chat to people through the chain-wire fence at the entertainment centres.

We all asked his personal bodyguard for photos of ‘Trigger’, Willie Nelson’s 1960s nylon string Martin acoustic guitar. The bodyguard actually wasn’t there for Willie himself but for his old guitar! That guitar used to have its own seat on the plane everywhere we went and the bodyguard never took his eyes off the thing.

Playing Trigger at a sound check was a bucket-list thing for me before I even knew what a bucket list was. That guitar played like butter in your hands. Holding it was like sitting in your favourite old saddle or slipping on your most comfortable boots. It was an amazing instrument and I would love to have seen half of what that old guitar had seen: concerts in huge stadiums; motel room jams with other great singers and songwriters; bus and plane rides across the world. I’d like to be that guitar for a week and gaze out on the thousands of people who have lived and loved the many songs that Willie has written on it.

During the tour Willie became very interested in Aboriginal culture. On his way through one of the big airports he bought a didgeridoo, but of course he didn’t have a clue how to play it, so he asked the local crew if they knew anyone who could show him how it was done. As I was the only Indigenous person on the tour, they all pointed the finger at me. So one night – I think we were in Perth – the summons went out and I was asked to go to Willie’s dressing room.

I approached the dressing room door with Willie’s minder and as it opened a huge plume of funny smoke emerged from inside Willie’s room. (He never touched alcohol while he was on the road, but I reckon coffee and weed kept him going.) Willie handed me his new didge and asked me to get a noise out of it. So I started to blow on it as Willie puffed away on his joint, filling the room with even more smoke. My uncles had taught me the circular breathing trick for the didgeridoo, so once I got started I could keep playing without drawing breath. Willie was flat-out amazed. Staring at me through clouds of smoke, he took the joint out of his mouth and said in his laid-back Southern drawl, ‘Man, how long can you blow on that thing?’

So I stopped playing and said, ‘Mate, I was gonna ask you the same question!’

After that, Willie started to have a whole new interest in what I was up to. I’d tell him about my family and he’d reflect on some of the Native American friends he had. Quite a few times, when I was doing my set, I noticed Willie sitting behind the stage watching and waiting for the song ‘Dream Out Loud’ to start because it featured the didgeridoo.

An edited extract from Things I Carry Around, by Troy Cassar-Daley, with Tom Gilling, published by Hachette Australia, $32.99.

Cassar-Daley will perform in the Tandanya Theatre from 7.30pm this Thursday, October 13, to launch his new book and album. Details here.