Tales from West Terrace Cemetery

The strange death of Francis Cluney, whose ghost may still haunt Adelaide Arcade, is one of many curious tales from the grave in Carol Lefevre’s “Quiet City: Walking in West Terrace Cemetery”.

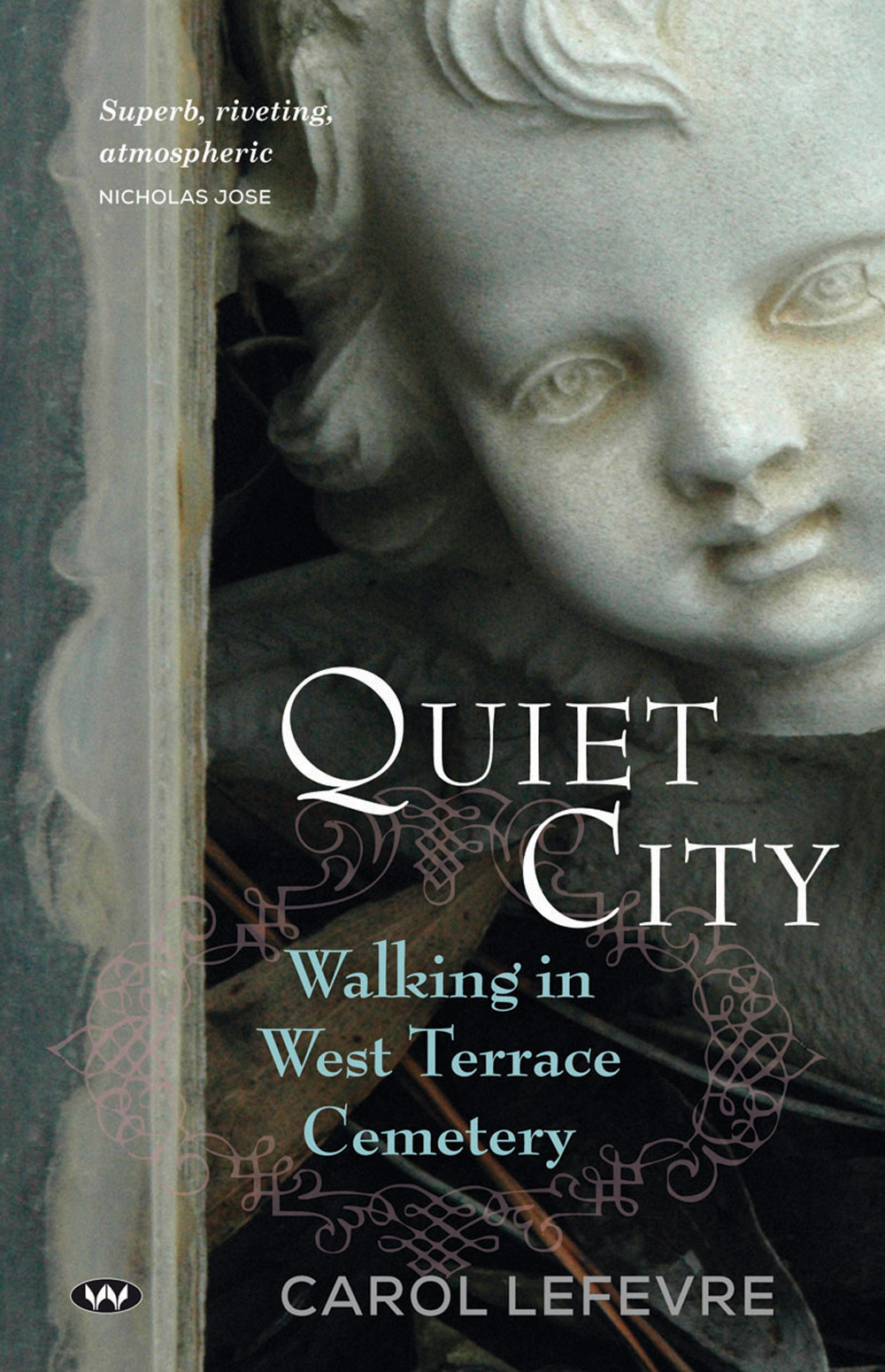

Stories from the grave. Photo from Quiet City: Walking in West Terrace Cemetery

Lefevre has studied headstones and archives to illuminate the lives of those buried in the heritage-listed cemetery, with their personal histories also revealing much about the social, cultural and political history of South Australia.

This extract below comes from chapter 11, Ghost Walk, which tells of the deaths between 1887 and 1904 of a number of characters associated with the Adelaide Arcade – and whose spirits perhaps still inhabit the building.

Ghost Walk

THE sky is overcast on this morning in late March. Stones gleam in the diffused light while trees subside into their own soft shadows. The angels on their plinths are luminous. Leaves silkily stir the hush, and there is the tingle of approaching rain. In short, it is the perfect moment for a ghost walk.

I do not think that I believe in ghosts, but just for this morning, just for the time it will take to ramble through this quiet city under clouds the colour of tin, or of pigeon’s wings, I am going to believe in them. South Australia is much haunted. The Old Adelaide Gaol is famous for it, although I wonder that the banks of the Torrens do not teem with ghosts because of the numbers who have perished in the river, especially children. The parklands, too, must have their sad spirits, Aboriginal men who were hung there for suspected crimes, and people without hope who contrived their own hangings. But this morning it is the ghosts of the Adelaide Arcade I plan to visit, and what an interesting crowd they are: Francis Cluney, the arcade’s beadle; baby Sidney Byron, and ‘Madame Kennedy’, palmist and clairvoyant; Florence Horton, young estranged wife of ‘Anglo the Juggler’. Reeling off their names I feel a ping of pride to inhabit a city strange enough to have been populated by such characters.

The Adelaide Arcade was officially opened on 12 December 1885. Mr Gay’s Furniture Warehouse and Barker Brothers Horse Bazaar had previously occupied the site. Mr Gay’s name has endured in the lovely arcade that opens off the eastern side. An orchestra played the ‘Adelaide Arcade Grand Polka’ at the opening ceremony. It had been composed by the Italian violinist Raphael Squarise; a newspaper cutting on display in the arcade’s museum shows a rather intense-looking young man with thick dark hair and shining eyes. He had studied at Turin and came to Australia as leader of the Cagli and Paoli Opera Company; when the company dissolved in Melbourne, Squarise came to Adelaide, where he led the orchestra at the Academy of Music, and the Theatre Royal.

The arcade was one of the first establishments to install electricity, still a novelty in 1885. The electricity plant was housed in a narrow room on the eastern side of the arcade. In it was an Otto Crossley horizontal gas engine, with two heavy flywheels each weighing a ton; the engine supplied the power for two dynamos, spaced about ten feet apart and connected by bands. The plant, once started up, was automatic, feeding itself with oil and requiring no particular attention.

Francis Cluney, the arcade’s beadle, was the equivalent of today’s security guard, and although the position was humble, Cluney was a well-known, almost public figure. He had been a sergeant major in one of the British regiments and had served in the Crimea, where he distinguished himself and won several medals. In his role as beadle, Cluney liked to dress in his old military uniform.

Henry Harcourt was the electrical engineer to the Arcade Company. On the night of Tuesday 21 June 1887 he left the machine room to install a number of electric lamps at the Adelaide Jubilee Exhibition. He put the beadle in charge, with instructions to see that the machinery was going on all right but not to touch anything, although Cluney was to shut it down if anything went wrong. He had often helped Harcourt start the engine. On this Tuesday in early winter, the lights were lit at 5.15pm, and Harcourt left the arcade just after eight o’clock. He had hardly departed, when all the electric lights went out and Charles Horne, an employee of Wendt’s jewellery shop, went to the machine room to see what was wrong. At the horrible sight of a pair of legs protruding from the workings, and clouds of gas escaping, Horne ran outside shouting that a man had been killed. Constable Pawson and the manager of the machine room at the Advertiser, Mr Simms, arrived together, and having turned off the gas saw that Francis Cluney had suffered a catastrophic accident.

About fifteen minutes before the lights went out – which must have been the moment Cluney fell into the machine – William Tuttle, a photographer, had needed the beadle’s help to deal with larrikins who had broken one of Tuttle’s frames in the arcade. The beadle helped him catch the offender and made him pay for the damage. If the larrikins went on like that, Cluney said, he would do what he had done the night before and put the lights out. Cluney’s body was found jammed between the engine and the flywheel. The injuries he sustained were terrible.

On the following day a coroner’s inquest was held at the Sir John Barleycorn Hotel. Edwin Burnett, a stationer’s assistant, testified that Francis Cluney was his father-in-law. Cluney had left a wife and seven children, the youngest only seven. He was not insured, nor was he a member of any benevolent society; he left nothing for his wife and children.

Rundle Street was not a pedestrian mall then, and newspapers of the time report that the street and arcade were busy. Why else would the man run from Wendt’s to see why the lights had gone out? Would a jeweller’s shop even be open now in Rundle Mall on a Tuesday night, especially a cold night in June?

***

Francis Frederick Cluney’s address is Road 1 North, Path 43, Plot 7. I walk from the main entrance down Road 1, and the path is on the right at the bottom just before the road swings left. I have come, expecting to find a memorial, something solid and respectful erected by the Arcade Company, or even a modest headstone got up by a subscription among the traders. What I find instead is a large number of unmarked graves; the soil is stony here, and it looks less kempt than other places. One or two of the plots, though bare, are touching in their detail: the spot beside the place where Cluney lies lacks a headstone but is carefully outlined with small white pebbles; there are artificial flowers in a vase, and terracotta edging tiles laid out flat at the foot of the grave. On Cluney’s other side the plot has also been outlined with stones; these have not been as carefully chosen and not all remain in place. In its centre a small heap of broken tiles and the remains of flowers poke from the reddish soil, the vestiges, perhaps, of something damaged and swept away.

Francis Cluney’s plot is bare but for a scattering of white pebbles. The only way I can tell that this is his last resting place is that on the map the graves of Thomas Tregoweth and Matilda Jane Abbott stand slightly behind his, and their headstones, especially Tregoweth’s, remain intact.

Standing at the spot where the beadle was laid to rest it occurs to me that if Francis Cluney haunts the Adelaide Arcade it could be for a number of reasons. The first is that the word ‘beadle’ has vanished from the working vocabulary. Next, and more compelling, is that the Arcade Company did not fund a monument to mark his grave even though he died while on duty. Third, and much more serious, is that the larrikin he forced to pay for the broken frame did not leave the arcade, but followed him into the machine room for a bout of push and shove. This is, of course, speculation. But as for the rest, I am sure that if I had been Francis Cluney, a man who still wore his old soldier’s uniform and medals with pride, I would have bitterly resented the lack of official recognition and I might have resolved, if it were possible, to return from time to time and express my displeasure.

I am about to move on, when the name Tregoweth again catches my eye, stirring a memory of a story about a different ghost. Constable Thomas Alfred John Tregoweth, whose family grave here includes a separate headstone for him, is said to haunt an area of Waterfall Gully close to the chalet that was once a kiosk and tearooms. In the hot December of 1929, a fire broke out in the gully and a carload of police arrived to lend a hand. Constable Tregoweth and a colleague were on the steep hillside above the chalet beating out flames in the long grass. When the fire crept up behind them, Tregoweth lost his footing and tumbled down the sheer slope, sustaining injuries and fatal burns.

Thomas Tregowth had survived service in the First World War in France; survived, too, being captured by the Germans and his twenty months as a prisoner of war. On his return from Europe he had joined the police force, only to lose his life in the Adelaide Hills. He left a wife and infant son.

Over the years there have been many sightings in Waterfall Gully of a young man dressed in the blue police uniform of the era. Almost all the reported encounters specify the colour blue, and he is thought to be a helpful ghost. Tom Tregoweth died, like Francis Cluney, in the line of duty, and here they lie not ten yards apart. In life the two were very different men, though both had been soldiers; in death it seems their spirits share the same restlessness.

From Quiet City: Waling in the West Terrace Cemetery, by Carol Lefevre, published by Wakefield Press, $29.95. Extract republished with permission.

Carol Lefevre has also published novels and short stories. She is a visiting research fellow at the University of Adelaide.