Book extract: First Person Shooter

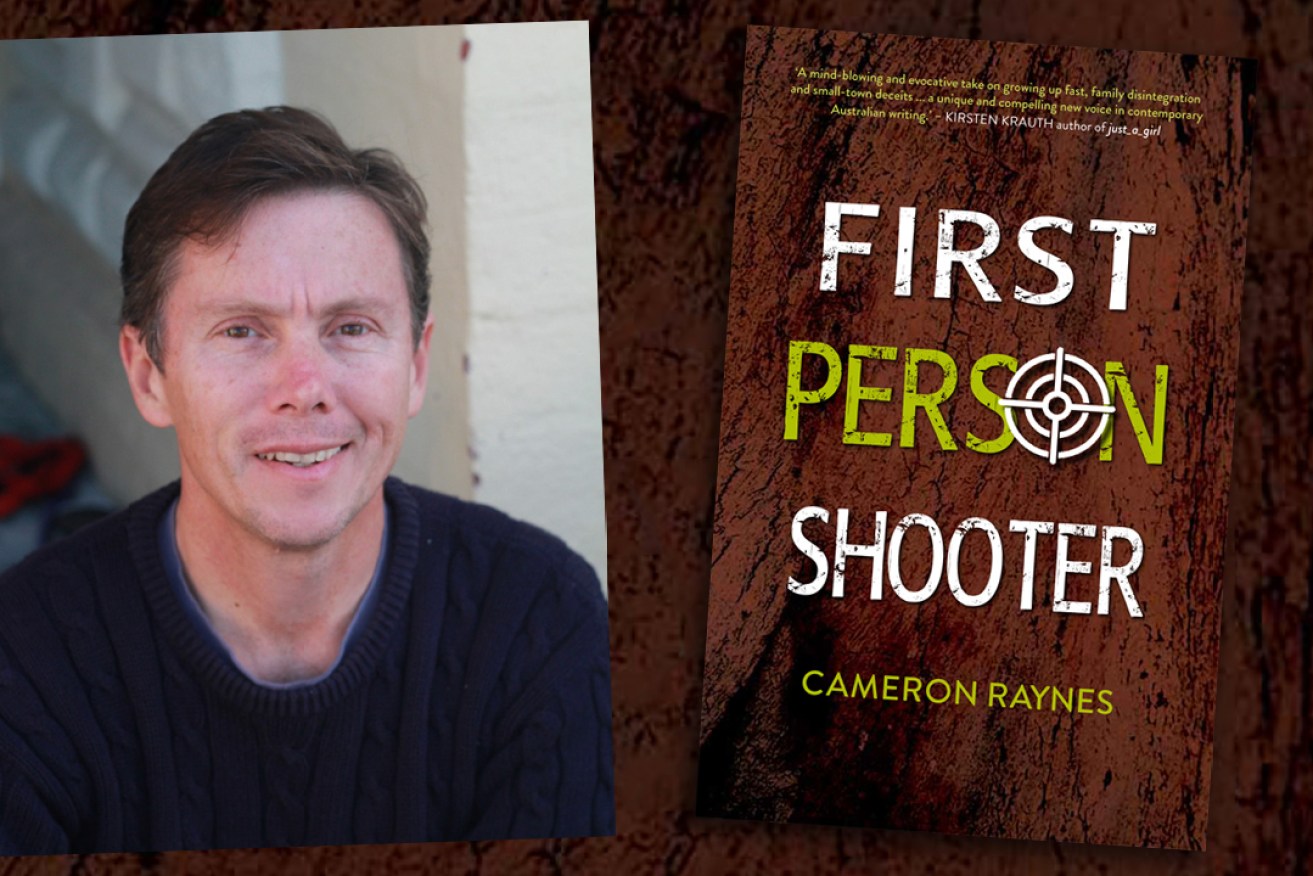

Adelaide author and teacher Cameron Raynes’ new novel is narrated by a teenage boy plagued by a stutter, addicted to video games, and living in a country town with bikie gang and drug troubles.

Cameron Raynes and his latest book.

Although Raynes, who teaches history at UniSA, is now an experienced public speaker, he drew on his own struggles with a stutter to shape the character of 15-year-old Jayden.

The following extract is taken from chapter three of First Person Shooter, when Jayden’s best friend Shannon’s mother Madeleine is about to be released from prison, prompting fears that her sociopathic stepson Pete will try to exact revenge for his father’s death.

***

I don’t want to let Shannon go off on her own but it’s just three kilometres home and she knows the bush tracks like the back of her hand. I’m expected at Max’s Meats anyway. She gathers up her backpack and sets off up Flanagans Hill and I watch her go for a moment or two.

Max’s Meats is a skinny little shop from the 1950s, squashed between Gavin’s Rural Supplies and the Salvo’s Op Shop. Across the road, Dreams Come True, a new age shop painted about three different shades of purple, like someone’s idiot kid did it and kept cutting the purple with white to stop it from running out. Its windows are boarded up. A bit ironic, given the name. Around the corner is Main Street and the second-hand bookshop, Dusty Jackets, where Shannon’s sister Jess works.

I push the big glass door open and step into the smell of meat. It will be all around me, in my lungs, mouth and taste buds for the next hour and a half, and for most of the way home until the wind and sun knock it out.

Old Mrs Watkins is at the counter, watching as Max bags a kilo of his best mince. Max is in his blue-and-white striped apron. He wears a black holster slung low on his hip like a gunfighter, rattling with knives. Those knives are razor sharp. He sharpens them on Japanese water stones every couple of days and strops them on a leather strap between customers.

Roger must be out the back. Max gives me a smile and I duck under the counter, grab my apron from the stand in the corner and pull it over my school gear. Past the chopping block, through the western-style swinging doors, past the cold room and into what I call the Gristle Room, but which is really the cutting room – the place where all the behind-the-scenes butchering happens. Where the other chopping block, bandsaw, mincer and sausage machine sit. It’s cool in here with its thick concrete floor and the A/C on. I can hear Roger outside, at the bins, so I cross the floor quickly and wash my hands at the trough with a cake of scratchy oatmeal soap, faster than Max would like but not fast enough to avoid Roger.

‘Washing the stink off?’ he asks, suddenly in the doorway, his apron bloodied around his hips. Roger is about forty, twenty years younger than Max, and has a gap where his lower front teeth should be. I suspect he had them punched out a long time ago. He’s as skinny as a lizard and there’s something scaly about him, especially around his eyes.

I figure his question is meant to be something about me and Shannon. There’s something a bit off about Roger, though he puts on a sweet enough show for the old ladies who come into the shop. I toss him a frown and grab the sieve, the rake and the shovel and head for the cold room.

My first job each Tuesday and Friday is to freshen up the sawdust in the cold room. The walls are plastered brick, thick and smooth, and the temperature is always three degrees Celsius, but I don’t bother about putting on the jacket hanging from the hook inside the door. ‘No brains, no sense,’ Roger always says, but it’s a nice change from the heat outside.

There are plenty of other things hanging from hooks in here. Three sheep, four cows, three pigs and two goats. Goat is becoming more popular. ‘That’d be the bloody Muslims,’ according to Roger. I have nightmares where I open the door to the cold room and there’s a body hanging there. A person, the hook shoved through their neck. It takes a while to get back to sleep after one of those.

A layer of fine sawdust covers the concrete floor. My job is to sift through the sawdust, filtering out any bits that have fallen off the carcasses – drops of blood, stray bits of fat or flesh – then toss them into the bin at the back of the shop. I start in the far corner and work back along the wall, raking, then shovel the messy bits into a sieve as round as Max’s belly. I crouch down, shake it back and forth and the clean stuff drops through the mesh. It’s like panning for gold, except what I end up with is a tray full of gross bits of dead animal. I tip them onto a sheet of butcher’s paper and start on the next section.

By the time I’ve done the whole floor, there’s enough dusty globs of meat to fill a lunch box. Roger reckons he’s gonna make me a pie with them one day. No thanks, I’ve seen what goes into the sausages. Sheep’s bums and bulls’ dicks. I rake the remaining sawdust until it’s spread evenly around, then take a big scoop of fresh stuff from the sack in the corner of the room and sprinkle it underneath the carcasses. The sawdust is pine and smells clean, like antiseptic. This is as good as the job gets. Everything is downhill from here. The scraping of the chopping blocks, the cleaning of the bandsaw and the cutting room floor. When I first started, I nearly spewed a couple of times and couldn’t eat meat for about a month.

Onto the butcher’s block next to the bandsaw. It’s a round slab of sheoak. These things are tight-grained, dense. Made to last. The scraper too. Stainless steel with a hardwood handle running the length of its edge.

Roger ambles over. Front teeth and politeness aren’t the only things he’s missing. On his left hand the middle finger ends at the top join and his ring finger at the first knuckle. Most butchers end up with less than the full deck of digits, according to Max.

‘Tell me something I don’t know,’ he says now, a change from his usual, ‘Whadayaknow,’ which I usually answer with a, ‘Not m-m-much.’

I rack my brains for something. ‘Madeleine’s g-g-getting out next w-w-week.’

‘Everyone n-n-knows that,’ he says. There it is. His little stuttering joke for the day. Out of the way. He lifts a shoulder of lamb onto the bandsaw and presses the green button on the side of the machine. It screeches into life. He lines up the first cut and pushes the meat and the fine-toothed blade rips through muscle and bone.

‘What’s the plan with Pete?’ he asks. Pete worked for Max and Roger when he was about my age, a decade ago. Max took him on as a favour to Madeleine, probably to get him out of her hair. Pete was a natural butcher, carving up dead things, but Max had to give him the sack when things went weird.

Roger makes a second cut, hits the red button and the machine dies a quick death. I shrug my shoulders at him when he turns around.

‘You gotta have a plan for him,’ he says. ‘He’ll be coming for Madeleine. Mark my words.’

Dad says it’s character building to work with people you don’t like. Says that’s what adult life is all about. He’s going through a really cheery stage at the moment. Still recovering from the car accident.

I keep at the block with the scraper. You have to put in a fair bit of effort, pushing the blade across the block at a low angle to lift up all the mess left behind from the chopping and cutting. Blood and fat mainly, with a strand of meat or sinew here and there. It all clogs together on the up side of the scraper and I wipe it on a scrap of butcher’s paper. Start again. When I’ve gone over the block three or four times and it feels dry to the touch I give the scraper a final wipe and head for the shop floor.

I get stuck into the big old block near the swinging doors, pushing and scraping at it while Max serves old Mrs Taylor. Flowery dress, lemony smell. She asks him about his granddaughter and Max leans his big, meaty arms on the glass-topped counter. Tells her she’s at university, studying to be a vet, and you can hear in his voice how proud he is.

‘From butchering to healing in two generations,’ he says, placing a parcel of lamb and rosemary sausages next to the hunk of silverside she buys every Tuesday.

Mrs Taylor wishes the girl well, then it’s her turn to tell Max about her own grandson, how he recently married a girl from the next town across. Max smiles and says to pass on his regards even though we’ve been hearing the same story every Tuesday for a year. Lately, she even forgets what meat she buys on what day, but Max always jumps in and is at it before she’s halfway into the shop. Maybe it’s to stop Roger. He’d probably serve her up a half kilo of French cutlets just to see the confused look on her face.

Bill Musgrave shuffles in. He’ll be after a kilo of mince coz he’s only got about three teeth left in his head and can’t chew. That’s what a diet of bourbon and cola does.

Then Mrs Taylor notices me in the corner and says ‘Hello Dear, how’s that girlfriend of yours?’ which makes me go bright red.

‘She’s good,’ I say.

‘I bet she’s looking forward to seeing her mum again.’

‘Yep.’

‘We’re all behind Madeleine, you know,’ she says, placing her parcels of meat carefully into her shopping bag. ‘Best thing she ever did. Shooting Terry.’

Extract from First Person Shooter, by Cameron Raynes, $24.99, published by Midnight Sun Publishing.

Raynes teaches history at the University of South Australia and is also author of The Last Protector and the short story collection The Colour of Kerosene.