Radical tenderness at the heart of scandalous tale

Nearing the end of his life, DH Lawrence poured a vision of radical tenderness into Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the ‘scandalous’ novel which UK writer Alison MacLeod says essentially led to a woman’s sexuality being put on trial.

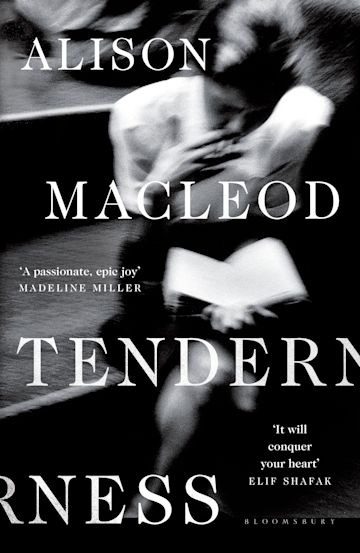

Alison MacLeod spoke via livestream with chair Felicity Plunkett (right) in an Adelaide Writers' Week session titled 'A Tender Lady Chatterley'. Photo: Tony Lewis

The 1960 obscenity trial at London’s Old Bailey over the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover took societal revenge on the fictional Lady Chatterley, a married woman who was essentially on trial for daring to have an affair.

“The phrase that comes to mind in both the courtroom and the hearing prior to it in London is what we now call slut shaming,” said UK writer Alison MacLeod, who joined Adelaide Writers’ Week via livestream from the UK to talk about Tenderness, her fictionalised history of DH Lawrence and his book.

“It wasn’t really a book being tried, as much as a woman’s sexuality being put on trial. That is evident throughout the transcript.”

DH Lawrence was gravely ill and haemorrhaging blood when he finished the book in the late 1920s, but he knew how scandalous it would be.

“This book is a bit of a revolution,” Lawrence wrote to a former publisher. “It is a bomb of a book.”

The frank accounts of sexual intimacy meant Lady Chatterley’s Lover could at first be published only privately by Lawrence, and by an Italian printer.

It was finally released in unexpurgated form in the US in 1959, where the FBI, headed by J Edgar Hoover, tried to have it banned, and in the UK in 1960, where it triggered one of the great trials in the history of free speech, with Penguin Books defending itself against charges of obscenity.

MacLeod said that as part of the evidence against Penguin, prosecutors forensically studied the text, tallying up “bouts” of sex (there were 13) and a list of dirty words, which the prosecutor read out. Following six days of trial and a short deliberation, the book was found not to be obscene, and when it came out a month later it sold 200,000 copies on the first day.

MacLeod said that as part of the evidence against Penguin, prosecutors forensically studied the text, tallying up “bouts” of sex (there were 13) and a list of dirty words, which the prosecutor read out. Following six days of trial and a short deliberation, the book was found not to be obscene, and when it came out a month later it sold 200,000 copies on the first day.

“Lady Chatterley herself was on trial and, in a sense, Lady Chatterley walked free,” MacLeod said.

MacLeod unearthed new evidence for the inspiration for Lady Chatterley, assumed to be Lawrence’s wife Frieda. But the writer concluded she was modelled on a woman called Rosalind Baynes, with whom Lawrence developed a five-year fixation.

“Lawrence had an intensity about him that led him to have obsessions with women.”

Baynes, the daughter of a renowned sculptor, was in a failing marriage and Lawrence engineered a meeting in Florence where he initiated an affair. They were together only briefly, but MacLeod said the notion of a contemporary novel based on a failing marriage stayed with him.

“It’s not really been examined before and I found it interesting – most of us assumed it was about Frieda Lawrence, an aristocrat who had an affair with a working-class man, who was the model for Lady Chatterley. But it is Rosalind Baynes’ appearance who influences in quite a detailed way Lady Chatterley, with her colouring, with her fresh country-girl look.”

MacLeod said she called her book Tenderness, a title Lawrence had considered for his novel, because for him the word encapsulated a level of honesty that represented everything he stood for.

“In Lady Chatterley, his last novel as he was dying, he poured the last of his artistic vision,” she said. “The more I spent time with Lady Chatterley, and its varied history, the more I became aware that radical tenderness was, above all, the bomb waiting to go off.”

Adelaide Writers’ Week continues in the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden until March 9. InReview is reporting from Writers’ Week each day – read coverage of other sessions here.

Read more 2023 Adelaide Festival stories and reviews here on InReview.