Australia’s forgotten heroes: ‘They were fighting two wars’

Stories of heroism, mateship, discrimination and heartbreak are shared in an exhibition that uses family histories, photos, objects and art to highlight the war experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Reg Saunders, the first Aboriginal Australian to be commissioned as an officer in the Australian army, surrounded by his mates of the 2/7th Battalion, AIF, in 1943. Photo courtesy Australian War Memorial

“They were fighting two wars: one overseas and one on the home front,” says For Country, For Nation consultant curator Amanda Jane Reynolds, reflecting on the experiences of Indigenous Australians during World War I.

“They weren’t even recognised as citizens, yet thousands and thousands of people did sign up and were fighting for country, fighting to be recognised as part of broader Australia and fighting for hope for the future.”

The stories of these soldiers and numerous other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and communities are shared in For Country, For Nation, an Australian War Memorial touring exhibition opening at the Samstag Museum of Art on ANZAC Day, which reflects on the experiences of First Nations people during conflict and peace, both at home and abroad.

Alongside historic text, photos, artworks and objects – including war medals and military paraphernalia – are works by contemporary Indigenous artists including SA glass sculptor Yhonnie Scarce and official war artists Tony Albert and Megan Cope.

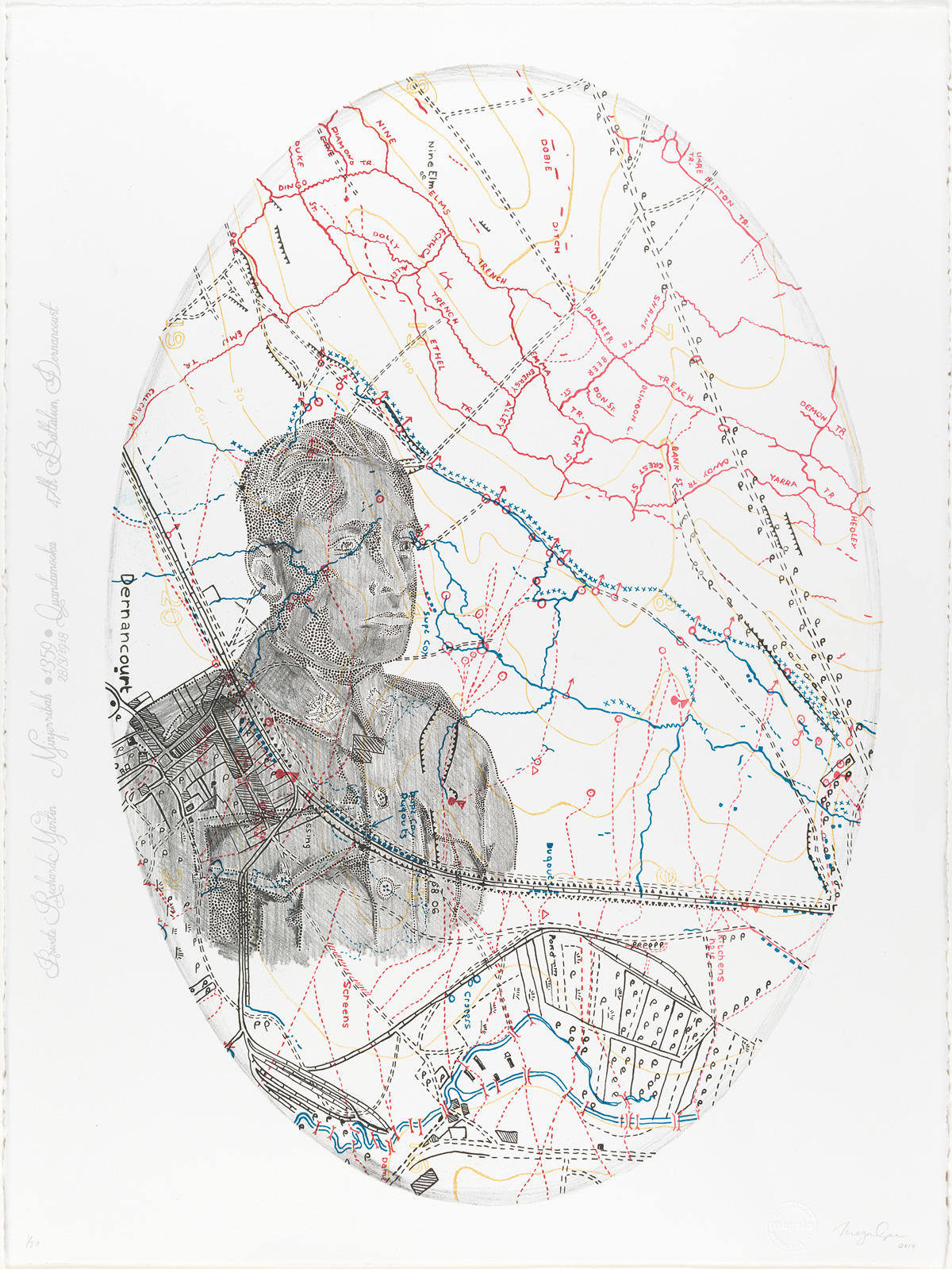

Megan Cope’s portrait of her great-uncle, from the Anzac Centenary Print Portfolio Lithograph, screenprint. Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial

Rather than being presented chronologically, the works are shown within six themes.

One of those themes, Human Rights and Social Justice, illuminates the different reasons individuals enlisted, and shares stories of the lengths they had to go to, including changing their names or convincing officials they were of “substantial European origin”.

The medals from young SA Private William Ridgway Rankine, who served on the Western Front in World War I, are on display alongside a quote from the Chief Protector of Aboriginals in South Australia saying that “as legal guardian of all half-caste Aboriginal children” he consented for him to enlist, “he being under the age of 21”. At that time, discriminatory legislation denied Indigenous Australians the right to make decisions about their own children.

“That’s just an example of the hoops service men and women went through over many generations,” Reynolds says.

“And then there was the sadness and betrayal, post-World War II, for example, of coming back home and some of the missions and reserves which had been put aside for communities were reclaimed back and carved up as part of the soldiers’ settlement scheme, yet there’s only a handful of cases where Aboriginal people were able to participate in that.

“They returned back to the same discrimination and had to continue to fight for rights, and as we know, recognition is still being fought for in our community.”

The stories shared also offer insight into the lives of Indigenous people on home soil in wartime Australia, such Larrakia woman Louisa Cubillo, who was evacuated from Darwin with her nine children during World War II. Her daughter, Larrakia elder Mary Lee, recounts how they were allowed to take only one suitcase between them, and how after they left her father was killed during an air raid while he was working on the wharf in Darwin.

They used to come in busloads to look at these black refugees

The Cubillo family ended up spending four years in a camp at Balaklava Racecourse in South Australia, where Mary Lee says they went through the degrading experience of being viewed by people bused out by a tourist company: “They put us on the agenda … they used to come in busloads to look at these black refugees and to roam around to see how we lived, slept, ate, went to the toilet and everything.”

Reynolds says the creation of For Country, For Nation was a highly collaborative process which saw the curators working closely with a group of national elders and knowledge-holders.

They helped workshop ideas for the exhibition’s themes, which, in addition to highlighting the experiences of individual service men and women, also focus on areas such as the warrior tradition within Aboriginal culture, the ways Indigenous communities have been affected by military activity, and how memories are handed down through performance, stories and art.

The exhibition includes multi-media experiences and a touch screen where visitors can view additional stories, including excerpts from letters sent during war.

“All those different media are expressions of voice,” Reynolds says

“Every single story has first-person voice, if not from the person then from their family talking to their history or documents from the time.”

The contemporary artworks in For Country, For Nation offer a range of responses to conflict. Among them a glass sculpture called Blue Danube by Yhonnie Scarce, who was born in Maralinga and belongs to the Kokatha and Nukunu peoples.

Yhonnie Scarce’s Blue Danube [black], Melbourne, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and This Is No Fantasy + Dianne Tanzer Gallery

Displayed under the Communities on the Front Line theme, Blue Danube is part of a series Scarce created in response to the atomic weapons testing that occurred in Maralinga during the Cold War era. “It just gives a small insight into the lasting impact of that nuclear testing and the loss of country it caused,” Reynolds says.

Scarce herself writes of her work: “There’s a bomb site out at Maralinga called Breakaway and it is so hot that the ground turned to glass. Apparently when it first happened there were sheets of glass all over the landscape but now there’s little shards that look like glitter. Not being able to access our country makes me upset. It’s been desecrated without our permission and we can’t go out there because of the health risks. For me, it’s about using my body to create these objects that refer to culture.”

Other contemporary works include a portrait by Queensland artist and Quandamooka woman Megan Cope of her great-uncle, Private Richard Martin, who fought in World War I and was killed in 1918 while defending allied lines near the French village of Dernancourt.

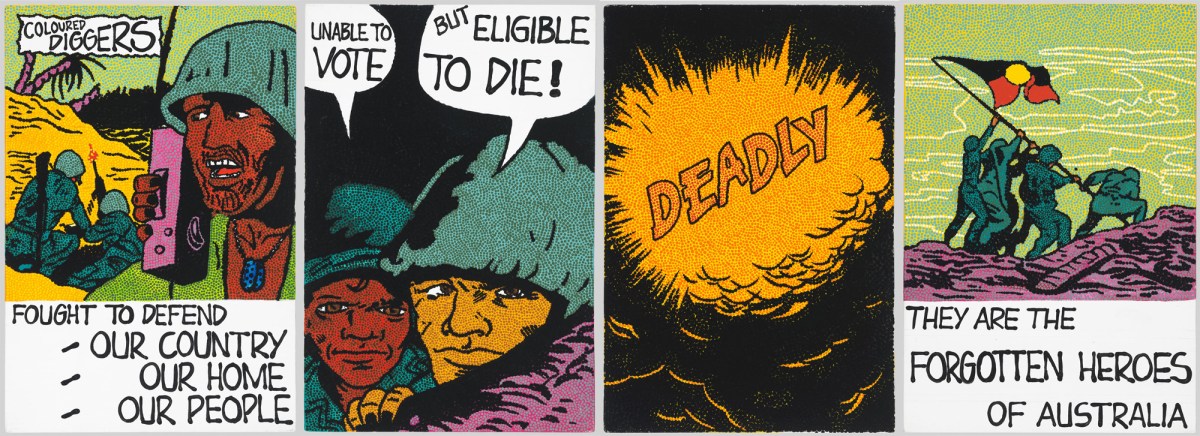

There are also works by Tony Albert (the 2016 Fleurieu Art Prize winner), who is said to draw on his grandfather’s World War II service and post-war experience as inspiration. His comic-strip-style painting Coloured Diggers gives a stark depiction of the inequality experienced by Australia’s “forgotten heroes”.

“It’s a very popular and much-discussed piece,” Reynolds says.

Tony Albert’s Coloured Diggers, acrylic on canvas, 2013. Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial

Visitors to the exhibition are welcomed by a didgeridoo soundscape and a large work by Victorian weaver Aunty Glenda Nicholl, We Remember, which comprises a woven fish net and feather flowers. It is intended as both a symbol of welcome and of commemoration of Indigenous service, and has grown to included hundreds of poppies which people were invited to attach to it while the exhibition was at the Australian War Memorial.

Reynolds says that while the lack of recognition of Indigenous service people over many decades had a devastating and heartbreaking impact, For Country, For Nation is helping inspire further education and projects to raise awareness of this important part of Australia’s history.

“We have found there’s been huge support.

“The desire to recognise and give justice is so long overdue, and people have been waiting such a long time for this chance and this opportunity, that everyone just wanted to do the best they could to get this story our.

“There’s thousands more stories than what are included in this exhibition.”

For Country, For Nation launches at the Samstag Museum of Art on ANZAC Day alongside Reality in flames: modern Australian art and the Second World War, a separate exhibition which explores how Australian modernist artists – including Nora Heysen, Sidney Nolan and Albert Tucker – responded to World War II. To celebration the opening of the exhibitions, the museum has planned an afternoon of events including live performances and a panel discussion with speakers including Amanda Jane Reynolds and Megan Cope (details here).