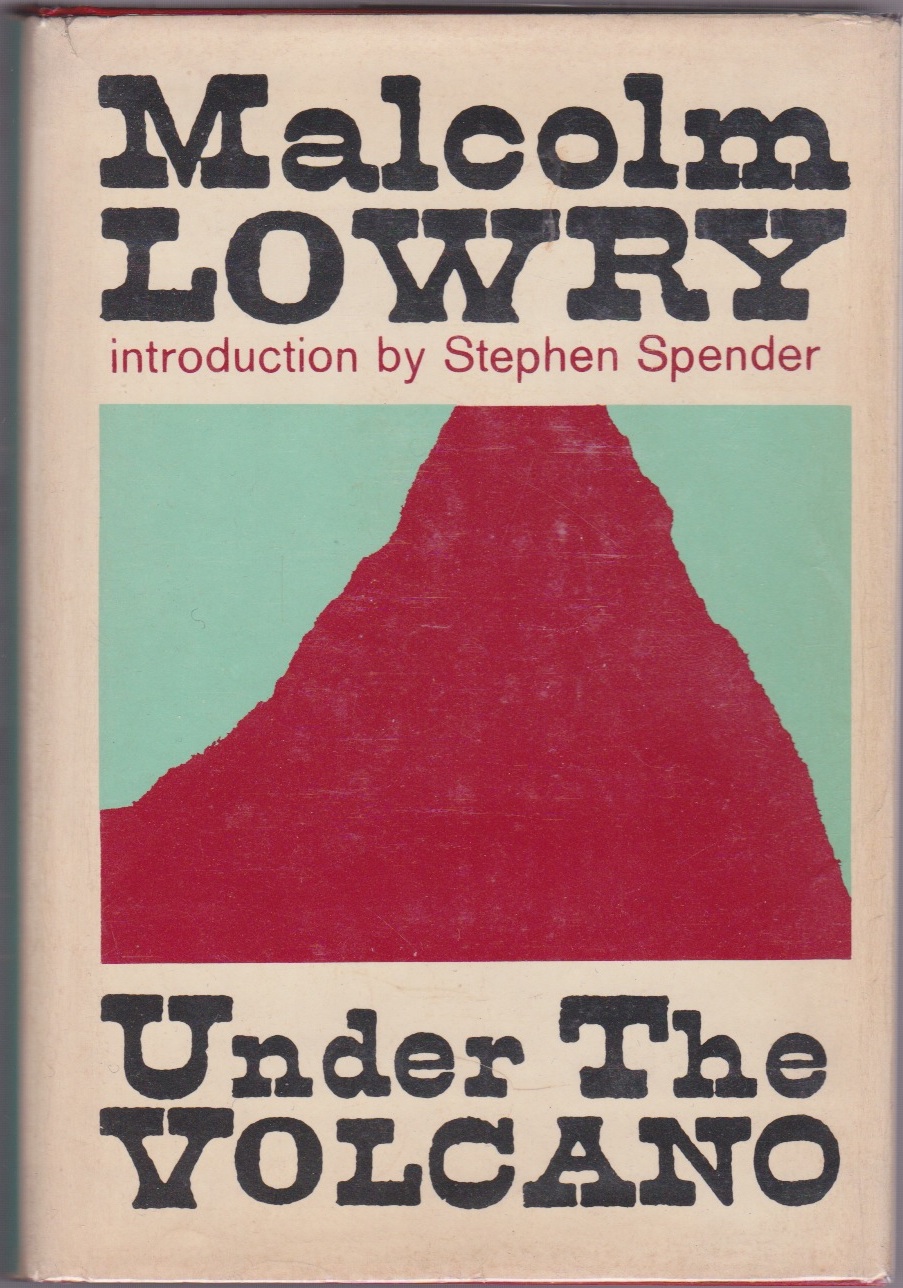

Books that changed the face of fiction: Under the Volcano

In this first article in a series about books that have changed or challenged fiction, Adelaide author Stephen Orr looks at Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano – a booze-soaked novel that is far greater than the sum of its parts.

There seems a niche market for alcoholic, abusive, self-destructive writers with a death-wish. Dylan Thomas, Hemingway – although Malcolm Lowry was, and is, by far the most interesting drunk scribbler. He suckled the teat at 14 because he felt neglected by his mother and, later, guilty (for the rest of his life) about the suicide of his Cambridge room-mate, Paul Fitte, whose homosexual advances Lowry had rejected.

Under the Volcano is an alcoholic novel. Reviewers and commentators can’t last long without reaching for a glass, or bottle, of the Consul’s mescal. The Consul being Geoffrey Firmin, the protagonist (although that term suggests forward movement, and the Consul really just stumbled), who is in fact an ex-consul, as there are no British interests in the Mexican town of Quauhnahuac, nestled below a pair of volcanoes with names too long and unpronounceable to bother with.

This is the booziest of novels. Not bad booze, destroying the Consul, but some sort of magic water, creating him from the ground up.

But now the mescal struck a discord, then a succession of plaintive discords to which the drifting mists all seemed to be dancing … It was a phantom dance of souls, baffled by these deceptive blends, yet still seeking permanence in the midst of what was only perpetually evanescent, or eternally lost.

Malcolm Lowry in 1946. Photo: New York Times

Lost, like Lowry (1909-1957) himself, born and raised in relative comfort, teenage golf champion, an honours degree in English. But like all great writers, he couldn’t give a shit about that.

To his parents’ horror he worked as a deckhand on a steamer for five months in 1927, later incorporating this experience into his first, forgettable, novel, Ultramarine (1933).

He then might’ve drifted back to a comfortable teaching job, or bank, but instead, set off on one of the most remarkable writing lives imaginable, his discontent and self-loathing stirring in the bottom of a bottle of tequila’s big brother, mescal. And Lowry was the worm, a lush, soaking it all in until his tragic, mysterious death by grog, or pill, or misadventure (you decide).

Because Under the Volcano is one big misadventure. Eleven of the 12 chapters are set (fittingly) on the Day of the Dead (November 2) in 1938. Firmin is constantly pissed. He is Lowry, and Lowry the Consul, wandering the world in search of … meaning, more booze, or (like Hemingway rising early, going downstairs and fetching his shotgun from the basement) death. The Consul is Faust (reappearing constantly in the text) making a deal with the devil, offering up his soul for alcoholic salvation. This is a book full of symbols, especially horses.

… Ah, to have a horse, and gallop away, singing, to someone you loved perhaps, into the heart of all the simplicity and peace in the world; was that not like the opportunity afforded man by life itself?

Because here’s the thing about Volcano: like the best books (Ulysses, The Bible), it’s far greater than the sum of its parts.

In a sense, it just concerns Firmin, his unfaithful wife, Yvonne, who returns to him for this single day (the 12 chapters matching the 12 hours he has left), and his brother, Hugh Firmin, who’s had an affair with Yvonne (there are others). All these people betraying the central figure of what’s become (after being out-of-print at the time of Lowry’s death) one of the 20th century’s top 10 books.

All the great themes are explored – for example, our failure to meet our potential (the failed consul Geoffrey, the failed actress Yvonne, and Hugh, the musical child-prodigy who never made good). The book rings with poetry (‘I have resisted temptation for two and a half minutes at least’), sings the most lightly-worn philosophy (‘How, unless you drink as I do, could you hope to understand the beauty of an old Indian woman playing dominoes with a chicken?’), drips with a near-proof feeling of presence, place and being that saturates each page with the God of Death (Mexican style), of threat (the ever-patient volcanoes), the cheapness and briefness of life, the futility of trying in a world where everything has been decided, long ago.

All the great themes are explored – for example, our failure to meet our potential (the failed consul Geoffrey, the failed actress Yvonne, and Hugh, the musical child-prodigy who never made good). The book rings with poetry (‘I have resisted temptation for two and a half minutes at least’), sings the most lightly-worn philosophy (‘How, unless you drink as I do, could you hope to understand the beauty of an old Indian woman playing dominoes with a chicken?’), drips with a near-proof feeling of presence, place and being that saturates each page with the God of Death (Mexican style), of threat (the ever-patient volcanoes), the cheapness and briefness of life, the futility of trying in a world where everything has been decided, long ago.

Nothing is altered and in spite of God’s mercy I am still alone.

Alone. Lowry’s first wife, Jan, tried to help him, as did his second, Margerie, who supported him for years in a dozen different homes, especially their beach shack in Dollarton, Canada (across the bay from the SHELL refinery, its glowing sign missing its ‘S’), before this burnt down. The Volcano manuscript was saved from the flames by Margerie. Neither woman was Yvonne. Perhaps his mother, Fitte, or maybe Lowry was just born wired to be a writer, with its attendant miseries.

Lowry spent his life perfecting one book. He planned to make it the centre of a trilogy, a great myth to be called The Voyage That Never Ends, but spent the rest of his time fiddling with work that never matched the potential of Volcano.

This is a book that seems to defy explanation, that can’t be understood until read, until you are tumbling down the ravine, shot by the local police, coming to rest beside a dead dog whose name, reversed, might really mean God.

Stephen Orr’s latest book, Incredible Floridas, was recently nominated for the 2019 International Dublin Literary Award.