The suburban Adelaide address that could be the nation’s most important cultural site

In a leaky brick and aluminium warehouse in Adelaide’s western suburbs hides what has been described as one of the most culturally significant sites in Australia – and it’s a place that is perpetually under threat.

SA Museum director Brian Oldman at the museum's Netley storage facility. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

SA Museum Director Brian Oldman stands by the entrance of an old printing premises in Netley.

Surrounding him is a maze of metal racks, drawers and boxes – some draped with white sheets like forgotten attic furniture and others left exposed, their shelves tightly lined with tens of thousands of spears, boomerangs, shields and other cultural material embodying more than 60,000 years of living Aboriginal culture.

“What you have in this room is, in effect, the essence, the distillation, the summation of Aboriginal Australian culture,” Oldman says, motioning towards the rows of priceless artefacts before him.

“There is nowhere in the world that you can come into proximity with that other than here.

“Culturally, this is one of the most important places in Australia.”

The SA Museum holds the biggest and one of the oldest collections of Indigenous Australian cultural material in the world, with more than 30,000 spiritually- and anthropologically-significant pieces sourced – ethically or otherwise – from across Australia’s approximate 250 Aboriginal language groups.

The bulk of the collection was gathered during the 19th century – the SA Museum just the second institution of its kind in Australia when it was founded in 1856 – and later between the 1920s and 1970s, when a concerted effort was made by Adelaide anthropologists to start recording and collecting Australian Indigenous culture, spurred by fear it was slowly dying.

Even today the collection continues to grow, with museum staff having just finished cataloguing 150 new woven baskets as well as a plethora of contemporary Aboriginal art.

About 30,000 Aboriginal cultural objects are stored by the SA Museum. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

“We see ourselves very much as the custodians of the collection,” says Oldman.

“The collection is really the collection of the community groups who have the cultural authority for the area for which they have their culture.

“We simply look after it on their behalf.”

Stored behind lock and key and only opened to visiting Aboriginal groups and the occasional non-Aboriginal visitor upon request, the collection is at a crossroad between colonialism and modern-day museum practices.

There’s a remnant from the first Aboriginal flag, an Eora man’s wooden club that Lieutenant David Blackburn fashioned into a whip upon arrival in Australia on the First Fleet, and intricate contemporary Yolngu bark paintings.

Those pieces lie alongside 5000 spears, 3000 boomerangs, 500 bark paintings and drawers brimming with hundreds of intricately woven baskets, neck-pieces and sculptures, to name a few.

Only five per cent of the museum’s Aboriginal cultural material is on display – the remainder resides at Netley.

“It is incredibly humbling to be here,” Oldman says, “and I’m talking as a white European museum director.

“For people to whom these objects are at the centre of their country, their culture and their spirituality, I can only assume that’s how it would feel by a factor of 100 or 1000.

“They can see things that were made by their parents, their grandparents, their great-grandparents or even further back, and that’s redolent of their continuous culture of 60,000 years.”

A cut-out from the first Aboriginal flag, which was first flown in Victoria Square in Adelaide on “National Aborigines Day” in July 1971. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

Oldman has moved to a mezzanine overlooking the 170-square metre room and its bourgeoning collection of priceless objects.

The reason for his visit is not to boast about the collection – although the superlatives to describe it come thick and fast – but to speak about the unfortunate environment in which it is stored.

Behind him are rows of womeras – wooden instruments used to propel spears or darts long distances. There are about 2000 of them, all stored in the open without protective covering.

“They shouldn’t be on open shelves, that’s not how they should be stored at all,” Oldman says, shaking his head.

“Ideally, these should be contained in some way.”

The SA Museum’s team of collection managers have been fighting an uphill battle against the elements, which have quite literally leaked into the Netley building and risked damaging their collection beyond repair.

The problem lies not just with the building – which is prone to flooding and humidity when it rains – but a succession of governments that have failed to find the items a permanent home.

“We have had in the past multiple ingresses of water – rain events – and we’ve had water sheeting down walls,” says Oldman, motioning towards now-bare walls that once hung acrylic paintings.

“The collection is in totally unsuitable circumstances and that’s placing it at risk.”

The SA Museum’s storage warehouse in Netley. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

The circa-1970s warehouse was repurposed in 1999 into what was promised at the time as a temporary storage facility for the museum, which had rapidly outgrown its North Terrace site and was in desperate need of a modern storage space.

Twenty years later, Oldman reveals the museum is “at this point of time no closer to the long-term space”, despite it being at constant loggerheads with the State Government over the functionality of the building.

“It’s like trying to hold a gas in a colander – it’s just fundamentally the wrong instrument to do the job you’re trying to do,” he explains.

“By construction, the building’s got a cantilever roof, which are built to move around and they have air spaces, so it’s very difficult for us to control heat and cold.

“We have difficulty controlling humidity, we have difficulty maintaining moisture levels, and also it gives us problems regarding infestation.”

Much of the SA Museum’s Aboriginal spear collection is stored on open shelves. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

It’s a warped blessing that museum staff have been able to restore the 40 artefacts that have been damaged since the collection was moved to the storage facility, with the remaining items at perpetual risk.

“The things that have been damaged have been acrylic paintings, which we have been able to conserve, however, had our flood come in a little bit further across it would have hit our bark painting collection, which is all ochres and that would have been the end of that,” says senior collections manager Alice Beale, who joins Oldman.

“Every time there is a water ingress issue the entire collection gets put at risk because even if the water isn’t hitting that object directly there’s the humidity that can cause mould, warping and cracking.

“We now keep several paintings in corridors, which isn’t ideal, but we’ve had to store them there to avoid them getting wet.”

SA Museum senior collection manager Alice Beale with a womera. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

Beale recounts an incident one night in 2013, when sprinkler heads installed in the buildings’ ceiling accidentally set off, causing water to be spurted across the collection. She says museum staff were forced to work into the early hours of the morning vacuuming water off the ground to save the objects from irreparable damage.

“What you shouldn’t have in a museum storage area is water suppression for fire because the last thing you want to do is douse this collection with water,” Oldman says.

“This shows, fundamentally, that it is the wrong type of building.”

Compounding the issue is the nature of artefacts themselves, most of which are made from organic material and weren’t built to be stored in western museums for over a century.

“When the anthropologist at the time would have said, ‘Could I possibly have that?’ and they were given that, it could have been an object that the community would have discarded until the next ceremony,” Oldman says.

“We are looking after objects which, when they were first created, were not made to be there forever: they were ephemeral.

“If you were to lose the objects you would never get them back and yet they’re placed in this totally unsuitable building.”

An Enos Namatjira watercolour painted on a womera. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

One of the museum’s collection managers, Tara Collier, brings out an “incredibly significant” Enos Namatjira watercolour encased in a cardboard box lined with foam mouldings.

It’s a typical landscape reminiscent of the style of Namatjira’s celebrated father, Albert, whose works are displayed in museums across the world.

“The conservationists have stored it in this way because it doesn’t sit flat and to help reduce light damage,” Collier says.

“It’s also one of our more significant pieces, being a Namatjira, so we have prioritised it in this way.”

The piece is one of the luckier items in the collection. Only 10 to 20 per cent are currently boxed appropriately, with the majority left exposed on open shelves.

“It would be nice to have everything in a container even if a container is just a shelving unit,” Beale says.

“That would give it at least some barrier to protection, as opposed to things just being stored on open shelves.

“But until we fix the leaking situation there’s really not much we can do.”

SA Museum collection manager Tara Collier with her favourite item in the Aboriginal culture collection: toy horses made by children in the 1960s. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

The problem, in Oldman’s view, has been a lack of recognition from past governments and society, more broadly, of the importance of preserving Aboriginal culture.

Enduring prejudices in favour of European collections, alongside limited arts funding, has meant collections such as the SA Museum’s Aboriginal Culture Collection have been left by the wayside.

“It’s part of how Australia is developing as a nation in terms of acknowledging Aboriginal culture as the culture of the whole of Australia, and that’s part of the evolution of the whole of Australia,” Oldman says.

“Times are changing and it’s now more widely recognised that this is important and I think, historically, it may not have been seen as important as in fact, it is now.”

An Eora club that was converted into a whip by Lieutenant David Blackburn, who landed in Australia with the first fleet. Photograph: Tony Lewis / InDaily

That cultural shift has reached Parliament House, where moves are now underway towards finding a long-term storage solution for the SA Museum.

Premier Steven Marshall, who also holds the Arts and Aboriginal Affairs portfolios, set the ball rolling, pledging over the past two years a total of $3 million towards upgrades to the degrading storage facility.

The funding comes as the Government progresses with its plan to build an Aboriginal Art and Cultures Gallery at Lot Fourteen, in a building it says will be an Australia-first institution displaying the state’s collection of significant Aboriginal cultural material.

“We have been working very hard with consecutive governments to raise this up the issues table,” Oldman says.

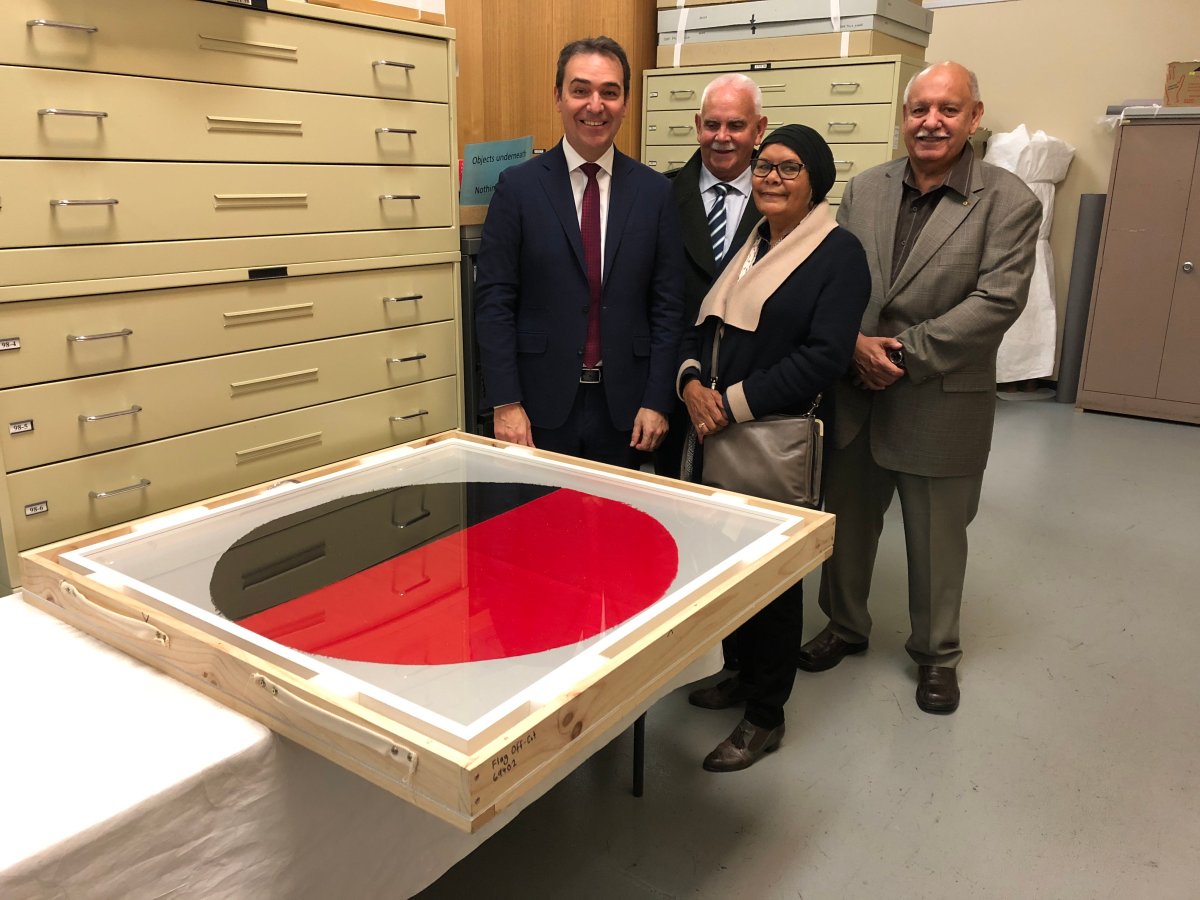

“What happened almost exactly 12 months ago to the day, is the museum’s Aboriginal Advisory Committee that is chaired by David Rathman, who’s an Aboriginal elder and who is on the museum’s board, he invited the Premier Steven Marshall to come down and see the collection.

“They were voicing their concern, on behalf of Aboriginal people, for their cultural heritage. That was the whole message of the Premier’s visit here.”

Premier Steven Marshall with the SA Museum’s Aboriginal Advisory Committee at the Netley storage facility in 2018. Photo: SA Museum

For Oldman, Marshall’s visit to the Netley facility planted the necessary concern to stir government from its slumber.

“We actually took a photo of the Premier and the Aboriginal Advisory Committee and he tweeted that this was his most exciting day of his year – and this was the year, of course, when he won the election.

“He gave us a verbal commitment here – in this space – that he would do something about it.”

From there, started a three-year process to prepare the museum’s collection for relocation to its new permanent home – at the Aboriginal Art and Cultures Gallery at Lot Fourteen or otherwise.

It’s a laborious project for museum staff, with each object to be individually handled, placed into proper international museum-designed containers, checked for conservation purposes, digitalised, stacked on palettes, barcoded and stored on new shelving units – all before the Government’s June 2021 deadline.

“That means that when the long-term home for the collection is defined – for example at Lot Fourteen – all the absolutely essential preliminary work that you would have to do to get this collection ready for effectively a forklift truck to come in, lift up the palette and take it to Lot Fourteen or another place,” Oldman says.

“This is the absolutely essential first step that must be done.”

SA Museum collection manager Tara Collier. Photo: Tony Lewis / InDaily

The end goal for Oldman, regardless of where the collection eventually ends up, is to create a “totally accessible” space for Aboriginal people to connect with the objects.

“At the moment, they have to book in advance to come here and they’re seeing it in a converted warehouse, so it’s all very inappropriate,” he says.

“What we would prefer is to have, in the correct environment, a collection aggregated on a community-wide basis for it to be much easier to come to the space with possibly less supervision so they can interact more closely.

“Beyond that, this is the material culture that everybody in Australia should be aware of – the culture of the land that they live on – and people need to be more aware of that long history.

“We would be very happy to see this collection being the cornerstone of any new gallery that is built.”

Want to comment?

Send us an email, making it clear which story you’re commenting on and including your full name (required for publication) and phone number (only for verification purposes). Please put “Reader views” in the subject.

We’ll publish the best comments in a regular “Reader Views” post. Your comments can be brief, or we can accept up to 350 words, or thereabouts.

InDaily has changed the way we receive comments. Go here for an explanation.