Pioneer’s risky dance move a gift to Adelaide

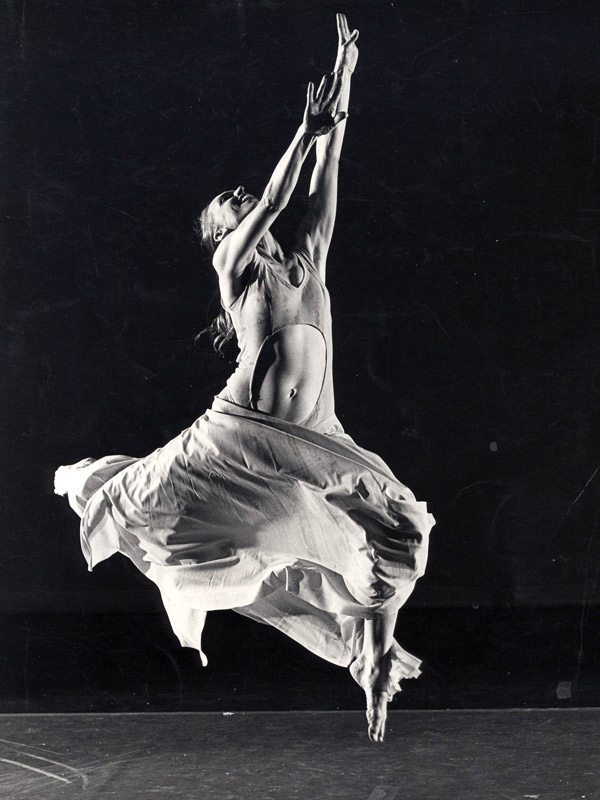

Elizabeth Cameron Dalman in Adelaide last week. Photo: Nat Rogers/InDaily

“Ugly dance impresses” is one of the review headlines Elizabeth Cameron Dalman recalls from the Australian Dance Theatre’s first performances.

It was the mid-1960s and contemporary dance was a new concept for both critics and audiences in Adelaide.

Not only was it more expressive than classical ballet, the dancers were barefoot. They danced to soundtracks ranging from classical to jazz, electronic music and – heaven forbid – even folk songs.

“Nobody had ever heard of anybody dancing to a folk song before,” says Dalman, who founded the Adelaide-based ADT.

“That was very, very avant-garde at the time.

“Australia was very conservative and the dance that was known as a theatrical form was classical ballet. There had never been any foreign modern dance companies here, so it was something different, it was something very new … very risky.”

But Dalman’s gamble paid off. While the critics may have been divided, she says audiences loved what they saw, hence the contradictory headlines.

Despite a sometimes tumultuous history – several of its artistic directors, including Dalman, left in controversial circumstances – Australian Dance Theatre has survived and is now Australia’s longest-running contemporary dance company, this year celebrating its 50th anniversary.

The planned anniversary gala was stymied by a lack of sponsorship. But Dalman – who still dances, choreographs and teaches, and was appointed ADT patron in 2013 – has stepped into the breach.

She was in the Adelaide Arcade last week filming a “mini-documentary” with a number of the other original ADT dancers, and will return on June 10 return to host a 50th birthday founders’ event in the arcade atrium featuring a cake cutting, music and a piece of repertoire from 1965.

Dalman will present another anniversary celebration in July, when she brings her own Canberra-based Mirramu Dance Company to Adelaide with the production L, in which she dances.

“Within that production there are several excerpts from the repertoire of the first 10 years of Australian Dance Theatre,” she says of L (which takes its name from the Roman numeral for 50, as well as L for Liz).

“It also tells the story of a dancer as she ages and how you keep a vibrant life.”

There can be few lives more vibrant than that of Elizabeth Cameron Dalman. Now 81, she seems to have endless energy and passion for dance, leading the way up several flights of stairs in Gay’s Arcade to show InDaily the ADT’s original studio before recounting the story of the company’s early years.

The Australian Dance Theatre began with seven dancers, she explains, but she worked with more than 70 over the decade she was there. She also founded an education program and dance school, and led tours interstate and overseas – including to places such as South-East Asia, where contemporary dance was a new concept.

From the age of three, Dalman had been a classical dancer. In her 20s, she studied classical ballet in London, then danced with a classical ballet company in The Netherlands.

“But I finally, after a long journey, found my way to the Folkwangschule [university of arts] in Germany, which was run by Kurt Jooss, and he’s known as the European modern dance pioneer.”

It was there she also met American choreographer Eleo Pomare, whose influence saw her switch to modern dance. Pomare became her mentor; the young dancer was inspired by his creative process, which in turn encouraged her to explore her own creative side.

When Dalman returned to Adelaide, she decided to establish a contemporary dance company in the city, despite the obvious challenges – it was a little-known performing art form, there was no government funding, and Adelaide was physically isolated from what was happening in other Australian cities such as Sydney and Melbourne.

At the time, classical ballet had a strong hold as the prevailing dance artform.

“There was a big divide between this whole modern movement and classical ballet, so we were kind of enemies at that time,” Dalman says. “A lot of classical ballet dancers would have nothing to do with modern dancers and vice versa.

“It seemed to be that we had not only different techniques but different philosophies – deeply different philosophies.

“The modern dancers were more about working in a team, more about developing the individual, a lot about expression, whereas in the classical ballet it was often to tear down someone’s individuality and implant this classical mould.”

In the 1970s, classical ballet and contemporary dance began to merge much more.

“I think classical dancers began to realise that they couldn’t keep this old-fashioned or traditional form going unless they embraced some kind of contemporary style and expression. And so that divide became less and less and there was more flow between the two.”

One of Dalman’s first dance works with the ADT was called This Train, and was set to songs by US folk group Peter, Paul and Mary. The same year it was presented, the singers came to Adelaide and Dalman met them after their concert.

“That led to many extraordinary experiences. We invited them to come and see a performance after one of their concerts, so at midnight our technical director managed to get the Rep Theatre and we performed for Peter, Paul and Mary. From then on, I kept a long connection with them.

“I made another work that was an anti-war expression to another of their songs, because they were very politically active.”

At the time, Dalman says, many Australian artists were expressing their political views, especially about the Vietnam War, through music, visual art, dance and other mediums.

“There were a lot of Australians saying, ‘Who are we as Australians?’ We were part of that movement of searching for an Australian expression.”

She hosted events she describes as “happenings” in the Adelaide home she shared with her husband, photographer Jan Dalman. Writers and artists would be invited, and on arrival they were handed sticks of incense with which to walk through the darkened home before gathering to hear and watch poetry, music and dance. Afterwards, the philosophical discussions began.

“There were a lot of these kinds of things going on in the ’60s … it was part of the whole kind of modern art movement that was questioning the traditional art forms, traditional places for performances to happen, and to find a voice,” Dalman says.

“It was a very important time in Australia – the Vietnam War got so many Australians on the street because Australia for the first time was saying, ‘We want our own identity; no longer do we want to be a colony of the motherland’.

“There had also been a big American influence because of the war … and there were a lot of Australians saying, ‘Who are we as Australians?’ We were part of that movement of searching for an Australian expression.”

Dalman says her own choreography was influenced by the Australian landscape – “the wide expanse and the beautiful country that we live in” – and Aboriginal culture and mythology.

Early ADT works raised some eyebrows with their inclusion of multi-media technology. In 1970, she collaborated with Polish stage designer Joseph Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski on a work called The Oldest Continent, which included laser beams and front and rear projection, and was presented at the Adelaide Festival.

The influence of rapidly changing new technologies, martial-art forms, acrobatics and multiculturalism have all played a role in the continued development of contemporary dance, with the scene today vastly different to that of the 1960s and ’70s.

“But it’s exciting that it has such widespread appeal for young people because it is a way they can express themselves; they can express their culture and who they are. It’s a wonderful vehicle for that.”

Since Dalman’s departure, the Australian Dance Theatre has had four artistic directors, including Jonathan Taylor, Leigh Warren and Meryl Tankard. Current director Garry Stewart took up the role in 2000 and has led the company on an extensive touring program with works incorporating new media such as video and robotics.

Dalman says that while it is disappointing the planned 50th anniversary gala was cancelled, ADT dancers will perform in Rundle Mall on the June 10 birthday, and the company will also present a work during the Mirramu Dance production at the Adelaide Festival Centre in July.

“It’s an interesting company, A, in that it’s been going so long and, B, in that there’s been such diversity among the artistic directors.

“I think it’s absolutely vital is that we are celebrating it in Adelaide. Fifty years for a contemporary dance company to survive is an extraordinary event worldwide, for one thing, it’s an extraordinary event for Australia and it’s more than extraordinary that it is in Adelaide.

“Even in my first 10 years when I was director it was twice posed to me that I should take it to Sydney and that it should not exist any more in Adelaide, and I fought tooth and nail that it be kept here and that it survive here, so I’m really, really proud.

“It has survived in spite of the fact that there’s been many very difficult bumps and dramas. It’s wonderful that it’s survived.”

As for Dalman, she won’t be retiring any time soon. Nor will she voluntarily stop dancing. She says she still enjoys it as much as she ever did.

“I do, but it’s very different, of course, because I’m more restricted now in how much I can do. I can still remember the utter joy when you’re physically young and fit, but it’s different – I like to explore the expressive capacity of dance. And I love working with younger people.

“I don’t believe in retirement. I’ve still got a lot of things I want to do. A lot.”